Book banning is a serious matter, and the American Library Association's annual Banned Books Week is an important consciousness-raising exercise. True, a lot of the titles on the ALA's list of targeted books have been "challenged" rather than actually banned, and -- thanks to the ALA's ability to mobilize the press and public opinion -- most of those challenges end up being disregarded or overturned. Still, every year dozens of citizens, usually parents, try to get books removed from school curricula and libraries.

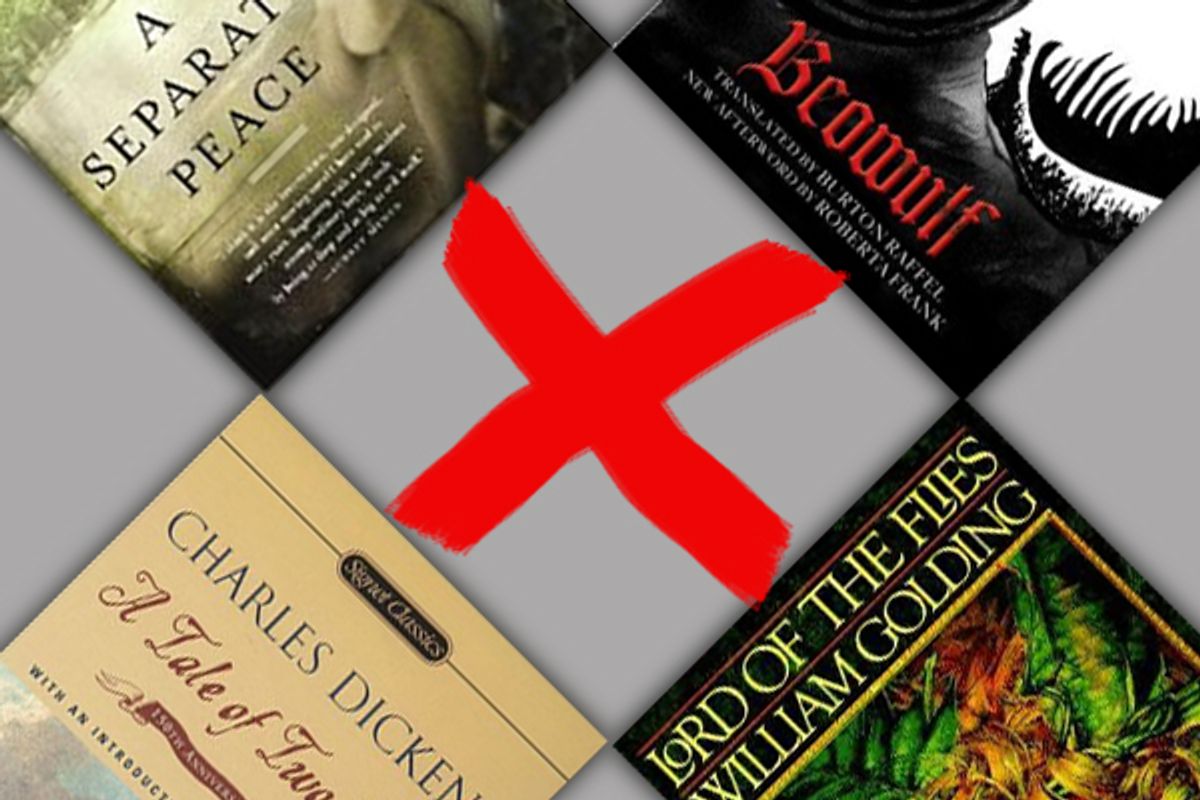

And so we ask: Where were these censors when we really needed them -- that is, when our 10th-grade teachers assigned "Beowulf" or "The Pearl"? As deplorable as real-life book banning may be, there's some required reading that those of us at Salon would love to see retired from the nation's syllabuses simply because we were tortured by it as kids.

"What is the educative value of making nerdy kids (or anyone, I suppose) read 'Lord of the Flies'?" asks film critic Andrew O'Hehir. "Is it pure sadism? To rub their faces in the gravity of their predicament, and the likely fact that they will sooner or later be sacrificed to a nonexistent God by their classmates? Now, I recognize the book's literary value, no question, and the point that it's an allegory about human society and not strictly about children or for children. But that's not how you read it when you're 11, for the love of sweet suffering Jesus. Really hated that experience."

For my part, while I was a voracious independent reader of children's fiction from the second grade on, "Lord of the Flies" -- and another novel I was ordered to read at age 10, "Animal Farm" -- convinced me that "grown-up" books were unrelentingly bleak and politically didactic; this kept me from venturing beyond the kids' section of the library for a few years. (Also: with "Lord of the Flies," I felt that the italicized allusions to "a stick sharpened at both ends" were so overwrought they must refer to atrocities even worse than putting someone's head on a pike. This caused me to imagine things no 10-year-old should be imagining.)

Even the most omnivorous reader has at least one middle-grade anathema, an assigned book that was nothing but one long, brutal slog. Sometimes we're simply too young for it; a man I know still shudders at the very mention of "A Tale of Two Cities" even though as an adult he came to love Dickens. Why make kids read a novel set during a historical period most will find difficult to grasp, especially as they wrestle with Victorian prose? I'm told "A Tale of Two Cities" gets put on curricula because it's the shortest Dickens novel, but "Oliver Twist" is only a little longer and its mistreated-orphans premise seems vastly more child-friendly. Could it be that "Tale" has a message ("Revolutions are nasty!") that adults find more congenial than the notions a kid might pick up from "Oliver Twist" ("Why not join a gang of pickpocketing urchins?").

Then there are the books that seemed pretty good at the time, but when revisited later leave you doubting the wisdom and taste of our nation's educators. Salon's editor in chief, Kerry Lauerman, got choked up over John Knowles' "A Separate Peace" as a high-school sophomore, but nowadays he'd prefer to see it jump from a high tree into a fast river. "I tried to read it again," he writes, "and I instantly recognized the easy life lessons and broadly drawn characters of a reality show or Lifetime movie."

But surely the most egregious tale of recklessly required reading comes from Life section editor Sarah Hepola, who at the age of 14 was assigned "Ivanhoe" by Sir Walter Scott, a novelist regarded as unreadable by most adults. "It was my freshman honors English class," Sarah recalled, "and it was the first book we read that year. English had always been my favorite class, a refuge for a kid who felt out of place and loved words, and that pretty much put an end to all that."

Readers, it's your turn: What book did you have to read in elementary or middle school that you wouldn't mind seeing vanish from the reading lists of children everywhere?

Further reading

The American Library Association's official Banned Books Week 2011 site

A Google Map showing places in the U.S. where books were challenged between 2009 and 2011, indicating titles, reasons for the challenge and ultimate results

Shares