Your book weaves the story of your family with larger topics, like the history of sugar, Brooklyn and dieting. How did you decide on the book's structure?

I believe you should have a really simple structure, and if you have a simple structure then you can do any weird thing that you want. To me the simple structure was just my grandpa Ben's life. His birth and then his death, and that was sort of the story of the family, and then I went into those other historical things only where I felt the history of my family and Ben's life touched on the bigger history. So when he invented the sugar packet, when he invented Sweet'N Low, he became involved in the history of sugar, and was also involved in ending the reign of sugar. So it was very natural there to have the history of sugar and the history of dieting.

What do you think are the "weird things" you did in your writing?

I just feel like it doesn't have to be one thing or the other. It doesn't have to be a memoir or a personal history or a business history or a social history. It can be all of those things. It can be between genres. If you look at the back it probably says memoir, but I don't think of it as a memoir, because it's not really about me. And it's about something bigger than my family, I hope.

Did you model your book on any others?

I kind of looked for a model but I couldn't find one. I have books that inspire me, that I think are great books, not in that I think I can make another version of this book, but in that they also seem to have no models. The idea is to write one of those books that, sort of, invents its own genre. I did look around and think, "Is there a book like this I can look at?" And I could not find one. It was scary, but it was also good.

You've said before that this is a book you've been thinking about writing for your whole life. When you actually sat down to write it, did it alter any of your own memories, make you re-evaluate the things you thought you knew?

Writing is a kind of thinking, so sometimes you don't even know how you feel about something exactly until you start actually writing. And then you start to see patterns of behavior, of people in my family, that I'd never really figured out before. I'm not somebody who knows what the book is going to be before I write it. Usually I have to write something twice. Once, before I have a sense of what it might be, and then I have to write it again.

Did you write this twice?

More than twice. Because it was on such a sensitive subject matter and I knew that I would probably try to censor myself, I decided not to censor myself at all and just write whatever came into my head about this, put everything into the book. I think the first version was 180,000 words long. I cut 100,000 words.

When you were cutting, was there anything you took out because of how your family might react?

Yes. There were things that I found out that I thought were too painful and weren't necessary for the story. It was just like a gaper's block or gawking. So if it was something unpleasant, and wasn't necessary, I took it out.

In light of writing a book all about your family, granted a large part of which wasn't all that nice to you, what do you think of Janet Malcolm's famous quote, "Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible"?

I think everything is morally indefensible. Every time you do something you hurt something, but if you go through life that way -- thinking that your main goal in life is to do no damage -- then you also can't make anything either. I do think that everything you do destroys something else in some way.

What's amazed me most about the book, and it's not really a surprise, I could have figured it out, but I thought that this story was really strange. That no one had a story like this. But I've been on this basically endless book tour and half the people I meet have either been disinherited or are in the process of disinheriting.

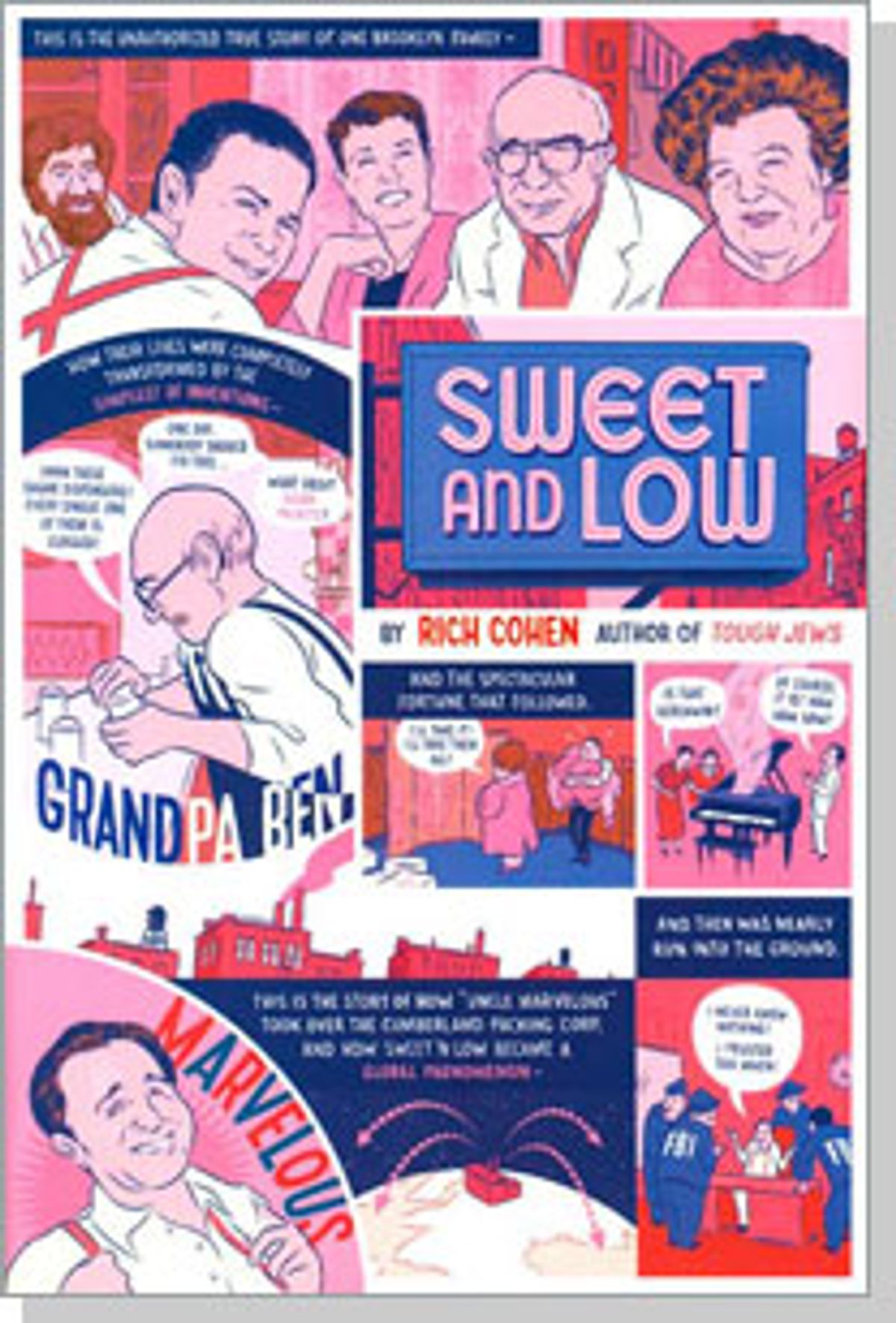

Excerpt from "Sweet and Low"

Everyone in my family tells this story, but everyone starts it in a different way. My mother starts it in the diner across from the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where my grandfather Benjamin Eisenstadt, a short-order cook, invented the sugar packet and Sweet'N Low, and with them built the fortune that would be the cause of all the trouble. My sister starts it with his wife, Betty, the power behind the throne, the woman who, in this version, found in Ben a vehicle for her dreams. Whenever anyone asks what Betty was like, I say, "Betty had her name legally changed to Betty from Bessie."

My father starts the story in downtown Brooklyn, in the courtroom where my Uncle Marvin, the first son of the patriarch, a handsome, curly-haired man who insists on being called Uncle Marvelous, is facing off against federal prosecutors. After assuming control of the Cumberland Packing Company, which makes Sweet'N Low, Sugar in the Raw, Nu-Salt, and Butter Buds, Marvin, among other things that caused a scandal, put a criminal on the payroll, a reputed associate of the Bonanno crime family. That criminal made illegal campaign contributions to Senator Alfonse D'Amato, who sponsored legislation that kept saccharin on the market. Saccharin, a key ingredient of Sweet'N Low, had been found to cause cancer. In the end, Marvin cut a deal with prosecutors, testifying for the government and keeping himself out of prison.

In other words, Uncle Marvelous turned rat.

I start this story at the Metropolitan Club, on Manhattan's Upper East Side, where my cousin Jeffrey, the oldest son of the oldest son, the scion of the third generation, is getting married for the second time. Jeffrey, a burned-out surfer, a bloodshot member of the high school class of '78 whose yearbook picture still tells the story, is earmarked to inherit the empire. If Jeffrey read more widely, he would know that he is fated to screw the pooch, lose his grip, open his hands and let the money blast back into the whirlwind.

Or I start with Uncle Ira, the youngest son of Ben and Betty, a vice president of the company, who controls 49 percent of the stock. Ira, who has always struck me as an extreme eccentric, is years younger than his siblings, a pampered, interesting kid who grew into a genuine nut, a man who carries a purse, wears sandals, follows whims, sports an unruly red beard, and lives in an East Side town house with his wife and many cats. Ira has been to his office at the factory just twice in the last ten years. (Though he says he works many hours a day from home via phone and fax.) He is the trick that fate played on empire, the inscrutable brother who has to be watched.

At Jeff's wedding, he approached me in the bathroom. Standing next to me at the urinal, he said, "What is the last thing you want your crazy uncle to say to you in the bathroom?"

"What?"

"Nice dick."

My brother starts the story in Flatbush, in the icebox chill room of my aunt Gladys, a woman who, for mysterious reasons, had not been out of the house -- her childhood home, where she still lived with Ben and Betty -- in almost thirty years. I once heard a politician describe a rival's tax scheme as "the crazy aunt hiding in the attic," and I said to myself, "She actually lives on the ground floor." Whenever I asked what was wrong with Aunt Gladys, why she never left her room, words were muttered about arthritis, psoriasis, lack of confidence. Even though she is the least physically active of the Eisenstadt siblings, Gladys, with her telephone, drives the action of this story. In a way I am still trying to fathom, Gladys is its protagonist. When I was briefing my brother-in-law on his new family and told him that Gladys had not left the house since the Nixon administration, he said, "You mean mostly she stays in the house but now and then she leaves the house to go to the store?" I said, "I mean mostly she stays in her room but now and then she leaves her room to go to the bathroom."

As I mentioned, my aunt's room, for reasons I still do not understand, is kept as cold as a meat locker. To this day, if we are in a movie theater or a mall where the AC is really cranking, my brother will say, "It's like Aunt Gladys's room, it's so cold in here." By which we know him to mean more than just the temperature: Gladys's room is where my brother, Steven, learned the nature of things. Once a week, before I was born, my brother and sister were taken to Flatbush to visit their grandparents, aunt, and cousins.

There was an ancient form of primogeniture at play in the family; as the son of the oldest son, Cousin Jeffrey was golden. One week, Grandma Betty decided that a grandchild would, for no particular reason, have a party thrown in his or her honor, complete with cake and gifts. While standing in my aunt's room, Betty wrote the names on a slip of paper and dropped the slips in a hat. A winner was drawn: Jeffrey. Since Jeffrey seemed to win many such contests, my brother grew suspicious. When he picked up the hat, Betty said, "Don't look!" Unfolding the slips, he had the great early shock of his life. Every ballot was marked "Jeffrey." Later, when my brother refused to follow some instruction, Ben led him upstairs and spanked him -- a grandfather who spanks! -- ending, for my brother, the sweet ignorance of childhood.

In 1995, when my grandfather collapsed in the hospital, the first relative on the scene was my brother. In a nice twist of fate, Steven found himself charged with making life-and-death decisions for the man who had helped him recognize the unfairness of the world. And the winner is? Jeffrey! In the months following Ben's collapse, the family battle moved into its titanic phase, with Ben shuffling from doctor to doctor and everything up for grabs: the money, the legacy, and the story itself. When Grandma Betty died, I found out that my mother had lost this battle and that she and all of her children had been written out of the will -- the factory and assets of the company are worth an estimated several hundred million dollars. Betty's last words came in a legal document: "I hereby record that I have made no provision under this WILL for my daughter ELLEN and any of ELLEN'S issue for reasons I deem sufficient." Her issue? It was like being called discharge, or refuse, or excrement. She swallowed a dime but it came out in the issue. So fate has placed me in the ideal storytelling position: the youngest son of the once-favorite daughter. Outside but inside, with just enough of a grudge to sharpen my sensibility. I am Napoleon staring at Paris from Corsica. All they have left me is this story. To be disinherited is to be set free.

Excerpted from "Sweet and Low" by Rich Cohen. Copyright ) 2006 by Rich Cohen. Published in April 2006 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved.

Shares