If you've heard of Jonathan Lethem, you probably heard about him the way I did, from a friend. The friend who turned me on to Lethem's last novel, "Girl in Landscape," did it the best way -- just opened the book and made me read the first paragraph:

Mother and daughter worked together, dressing the two young boys, tucking them into their outfits. The boys slithered under their hands, delighted, impatient, eyes darting sideways. They nearly groaned with momentary pleasure. The four were going to the beach, so their bodies had to be sealed against the sun. The boys had never been there. The girl had, just once. She could barely remember.

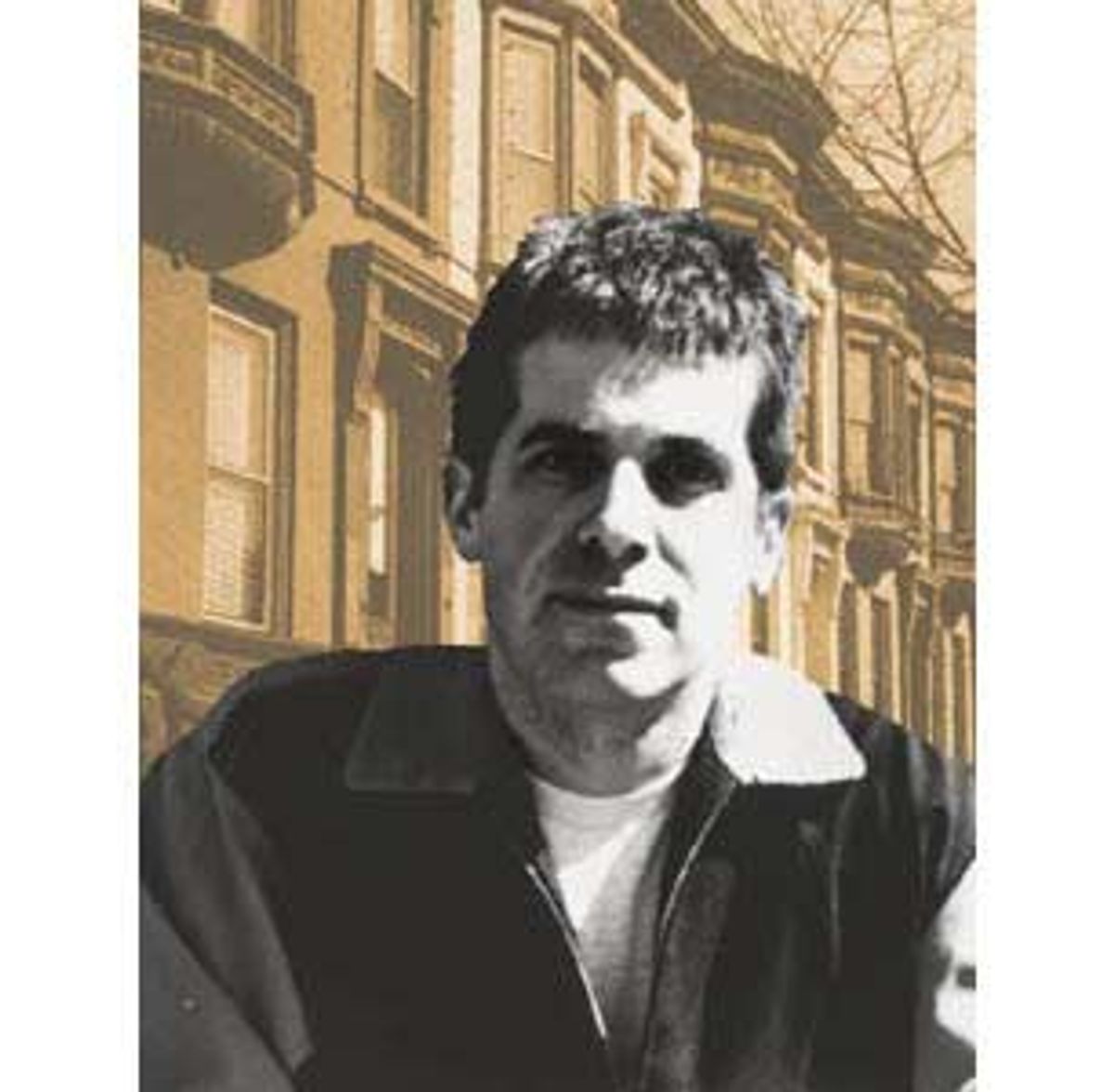

Since I first read those sentences, I have loaned or given copies of "Girl" to my little sister, my boss, a famous writer I admire, several colleagues, two foreign visitors and many friends. Most of them had never heard of Lethem for the same reason that you probably haven't -- not because he hasn't written much (Lethem has written five novels and one book of stories) but because until now he has written only science fiction and, by and large, science fiction doesn't get reviewed in the mainstream press. That will probably change with Lethem's new novel, "Motherless Brooklyn," a book that looks likely to complete his long, gradual crossover to full literary respectability.

I use the term "science fiction" loosely. It may be more accurate to say that Lethem is a genre writer, and a versatile one at that: He has written a western, a noir, a Philip Dick-style dystopic fantasy and an academic satire -- in other words, novels that obey conventions different from those of literary realism. Traditionally, the essential feature of science fiction -- that it unfolds in the future -- has seemed to give it prophetic powers, and the highest praise that we can give to a certain kind of science-fiction writer is that he or she got the future right. In Lethem's work, however, the futuristic setting functions like the words "once upon a time ..." It prepares us to enter the realm of myth, without telling us which myth, in particular, to expect.

Because "Motherless Brooklyn" is set in the present and recent past, and so is likely to end Lethem's cult status, now seems the time to set down some notes on the style of his early work, and the departure that "Motherless Brooklyn" represents. "Girl in Landscape," the western, shows Lethem's science fiction at its best. Lethem, who is his own most illuminating critic (and tends to talk about his novels as if they came out of a chemistry set), describes "Girl" as a mixture of the John Ford movies "The Searchers" and "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance." He admits that it "also owes scenes and dialogue to my favorite E.M. Forster novel, 'A Passage to India.'"

The premise is this: In the future, ozone depletion forces earthlings underground. An idealistic Brooklyn politician, widowed when his wife dies from exposure to solar radiation and -- disgraced by collapses of the subway tunnels in which New Yorkers now live -- resettles with his teenage daughter and little sons on what is called the Planet of the Archbuilders. There he hopes to build a liberal society in harmony with the indigenous people, but he soon runs afoul of the colony's de facto leader, a charismatic bigot who nonetheless seems to understand and fear the Archbuilders more deeply than the other humans do.

The story, which we watch unfold through the daughter's eyes, could hardly be more familiar, but everywhere Lethem unearths complications. We know (without being told) to read the strongman as John Wayne and the father as Jimmy Stewart; Lethem lets us imagine them talking and moving in bodies like the bodies of those actors. At the same time, he shows us the fertile ambiguity of their roles. If the father has a guilty past, if the strongman takes the place of the missing mother, if the western is also a novel of sexual awakening and if the novel of sexual awakening emanates a dreamlike flora and fauna of its own, none of this feels like pastiche, or parody, even when it makes you laugh. Lethem makes it seem organic to the genre.

For this reason, it's easy to say what Lethem's science fiction is about and wonderfully hard to say what it means. Take the Archbuilders, a hermaphroditic, ancient race haunted by the accomplishments of their ancestors and in love with the "'enchanting limitations'" of the English language. What do they stand for? Indians, of course. But Indians as sexual threats, as childlike originals, as belated poets, as unknowable mysteries, as victims, as Hindus, as Anglo-Saxons in the shadow of Roman ruins? What do Indians stand for?

Lethem's novels have differed remarkably from one another in genre and tone, but "Motherless Brooklyn" is flawed -- literally cracked in two -- like nothing that Lethem has written before; and so it also divides his body of work, between his California and his (new) Brooklyn periods. Set in the 1970s and '80s, the first third of "Motherless Brooklyn" describes the adolescence of the novel's narrator, Lionel Essrog, an orphan with Tourette's syndrome, rescued from the misery of St. Vincent's Home for Boys in Brooklyn when he and three other orphans are hired as movers by a tough guy named Frank Minna.

Lionel lives at the mercy of compulsions: to curse, to touch people and things, to echo and recombine words, to blurt out embarrassing thoughts. Lionel is hulking, funny, bookish, brilliant and horribly isolated: Aside from panic and mind-numbing drugs, sexual intimacy is pretty much the only thing that calms his tics (which gives some idea of the painful ironies at Lethem's disposal). Minna, by contrast, is a free agent: a witty street-corner hero who gets most of his self-respect from the adoring kids he calls, collectively, "Motherless Brooklyn."

In return Minna becomes their surrogate mother -- and their Brooklyn. He incarnates the tiny, mostly Italian neighborhood around Court Street that becomes, to Lionel and the others, "the only Brooklyn, really." From Minna Lionel learns the neighborhood's verbal style: "An endearment was flat unless folded into an insult. An insult was better if it was also self-deprecation, and ideally should also serve as a slice of street philosophy, or as a resumption of some dormant debate." And Lionel learns to see the neighborhood through Minna's eyes:

Hippies were dangerous and odd, also sort of sad in their Utopian wrongness. ("Your parents must of been hippies," he'd tell me, "That's why you came out the superfreak you are.") Homosexual men were harmless reminders of the impulse Minna was sure lurked in all of us. "Classic" minorities -- Irish, Jews, Poles, Italians, Greeks and Puerto Ricans -- were the clay of life itself, funny in their essence, while blacks and Asians of all types were soberly snubbed, unfunny. It was a form of racism, not respect, that restricted blacks and Asians from ever being stupid like a Mick or Polack. If you weren't funny, you didn't quite exist.

It's harder to say which comes more fully alive in the novel's first third, Minna or his borough. And when "Motherless Brooklyn" moves to the present day, and Minna is murdered, the borough -- and Lionel's powers of observation -- seem to die a little, too. As in Lethem's earlier detective novel, "Gun, With Occasional Music," the whodunit aspect of this novel is preposterous. Unlike "Gun," a very funny homage to Raymond Chandler, the second part of "Motherless Brooklyn" is a pastiche of cop shows and comic books -- high-speed car chases, a malevolent Polish giant, Mafiosi more "Godfather" than Gotti, a sexy widow suspect, a gang made up of doormen, a cult of sinister Zen tycoons, a mysterious woman who finds Lionel's disorder attractive ... and very little Brooklyn. Once Minna drops out of the story, Brooklyn vanishes, too, as Lionel travels to the wilds of Manhattan and even as far as Maine in his search.

You might say Lethem's holding a mirror up to the real Brooklyn, where he grew up and now lives after a 10-year stay in California. The Minnas and Essrogs have largely been replaced by yuppies --in particular young writers, editors and critics (if anyone really got rid of Frank Minna, it was Lethem's readers). "Motherless Brooklyn," Lethem freely admits, is the novel of his return. It sprang, he says "from the initial intoxication of my reunion, the rush of recognition and excitement I got from walking in my old footsteps and hearing people talk."

The recognition is partial. Lethem feels keenly how much the neighborhood has changed, but notes that even the working-class Italian Brooklyn depicted in "Motherless Brooklyn" is something of a dreamscape. "It's a fantasy of the Brooklyn I grew up in fulfilled in all its romantic potential. It's a best-case scenario that all the mugs hanging out in front of the barbershop were really the neighborhood fixers, immensely powerful figures. The truth is they were probably just mugs with nothing better to do than hang around."

Those barbershops have become cafes and antique stores. "It's a book about denial," Lethem explains. "Lionel and the Minna Men are a barrier holding back what's coming, the gentrification and Manhattanization. It's not Frank Minna's neighborhood anymore." And Lethem is careful to note that the Brooklyn he grew up in was never really Frank Minna's, either. The son of hippie parents, he spent his early childhood in a quarter of the borough where he was one of very few white kids and where regular beatings and muggings came with the territory. "I closely resemble the Manhattan hordes that have taken over the neighborhood," he says, "but I paid my dues. I can sit and drink a $4 latte on a corner where I vividly remember having had a knife held to my throat." Lethem says his next novel will deal with the tensions that riddled the version of Brooklyn he knew best as a child. "The topic I flinched from in 'Motherless Brooklyn' is the one I want to pursue now: race."

It was only when he got to junior high school that Lethem met white kids -- Italians like Minna and his second-in-command, Tony -- who felt they "owned" their neighborhood. For Lethem, Lionel gets to live out a fantasy of joining that brotherhood and knowing "what is it to be grounded and to feel at home somewhere. Most of my friends were white, but they were not like me. There were very few hippie kids. Admiring Frank Minna has to do with wanting to feel his sense of inheritance."

So, with an irony worthy of, well, a Jonathan Lethem novel, this writer has come back to a hometown that's entirely different, and yet full of people very much like himself. "I feel extremely comfortable here. I belong to the neighborhood. It just isn't the place it was. And I'm typical of the neighborhood now. I walk down the street and see people I know."

Shares