There's a corner in photojournalist Howard Bingham's current show at the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History where evil goes toe-to-toe with good. This may sound hyperbolic, but it's not, at least not by much. In this segment of "Main Event: The Ali/Foreman Extravaganza Through the Lens of Howard L. Bingham," evil is personified by the late dictator of Zaire, Mobutu Sese Seko, a man infamous for the plunder of his own people.

Images of the dour, sinister autocrat in black horn-rimmed glasses and leopard-skin chapeau fill an entire wall. Even without knowing the history of the man's barbarity and greed (the term "kleptocracy" was reportedly coined to describe his rule), his cold, sadistic stare alone can give you the willies.

"He is scary," remarks Bingham, 60, during a recent walk-through of his spectacular 130-photograph exhibition.

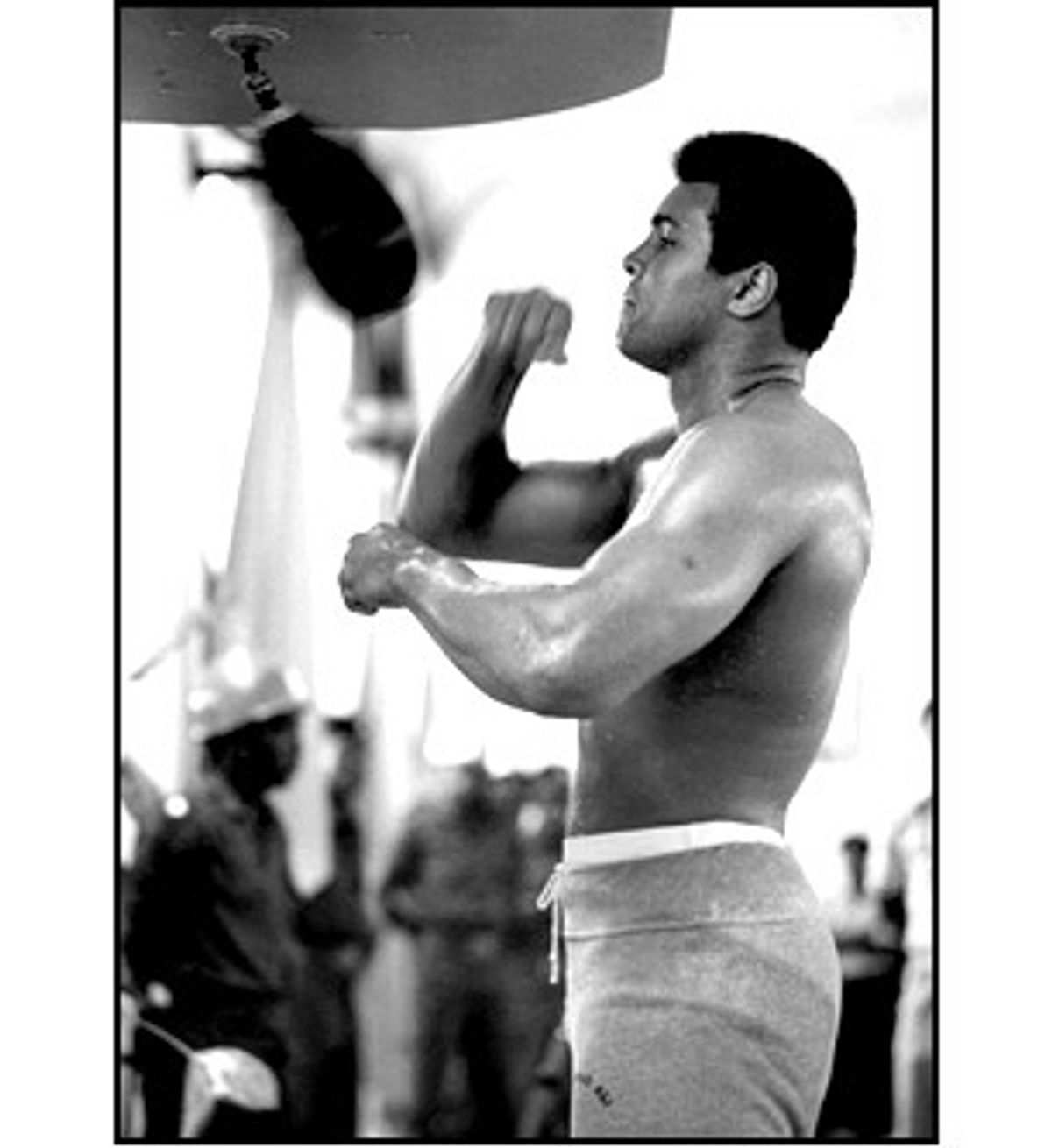

Color and black-and-white photos are mixed throughout the show. Culled from thousands of contact sheets and slides in Bingham's possession, the enlarged prints pay tribute to Bingham's eye -- his seemingly effortless ability to capture intimate moments in even large public events. It's a talent that's garnered him the American Society of Photographers International Award and the Kodak Vision Award as well as nabbing him the unusual honor (for a photojournalist) of being featured on a 1998 cover of Sports Illustrated, alongside Muhammad Ali, above a caption that reads: "Who's that guy with Howard Bingham?"

Renowned for his contributions to publications such as Ebony, Life and People, Bingham has shot numerous celebrities and public figures, among them Bill Cosby, Malcolm X, Sidney Poitier and O.J. Simpson (with whom he shared, coincidentally, a fateful plane ride to Chicago that got him called as a witness in Simpson's subsequent murder trial).

But it was Bingham's relationship with Ali that most profoundly influenced his career.

To the left of this wall, there are photos of a series of green-and-yellow signs with slogans from Mobutu's regime. They caught Bingham's eye while he was in Zaire in 1974 as Ali's personal photographer for the fighter's momentous bout with then-heavyweight-champion George Foreman, a match known thereafter as the "Rumble in the Jungle."

"I like this one," Bingham says, pointing and reading with just a hint of his famous stutter. "Black power is sought everywhere ... It is already realized in Zaire.' But you know, Mobutu was just talkin' smack and doin' something else."

In Leon Gast's 1996 Oscar-winning documentary about the fight, "When We Were Kings," Norman Mailer tells a story about Mobutu operating a prison underneath the very stadium in Kinshasa where the fight was held. Supposedly, Mobutu had rounded up all of the city's criminal element and executed a handful to show them who was boss.

"There probably was a prison underneath," says Bingham. "I never went down there to see. We didn't get into conversations like that there. I was in Ali's entourage, and people were always happy around Ali."

Bingham, a handsome black man with a warm smile and a salt-and-pepper beard, turns to the wall just to the right of Mobutu's -- one which displays a number of images of Ali. There could be no clearer contrast to the aloof and menacing Mobutu. The pictures depict Ali mugging for the cameras, resting in quiet contemplation on a couch and posed with a group of smiling schoolgirls, among others.

The energy radiating from these photos is the exact opposite of that coming from those of Mobutu. Ali is all warmth, humor and gregariousness. He is light to Mobutu's darkness. Bingham has captured Ali's generosity of spirit on film as effectively as he has captured Mobutu's rapaciousness.

"Mobutu actually died a little bit too late. In 1974, that guy was one of the wealthiest men in the world. In 1997 when he was overthrown, they said he was worth billions of dollars. The way he treated his country was really sad. When I was over there, I remember thinking I'd never seen soil so rich."

Looking at the photos of Ali kissing children and being followed everywhere by adoring crowds, it's easy to get the impression that had they been free to choose, the citizens of Zaire would have readily anointed Ali as their monarch.

"Ali's magnetism is him being honest to himself and to others," explains Bingham, who has been Ali's best friend for over 30 years, almost as long as he's been a photographer. "He not only says something, but he does it."

Bingham is referring to Ali's decision to refuse induction into military service during the Vietnam War because of his religious and moral beliefs. A new book by Bingham and writer Max Wallace, "Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight: Cassius Clay vs. the United States of America," relates how Ali took his battle all the way to the Supreme Court, which eventually ruled in his favor. But in the meantime Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title and excoriated in America for his refusal to serve.

"He gave up millions of dollars from 1967 to 1971," Bingham says. "If he'd gone into the Army, he would've had it made. He would've never seen a war. But he couldn't be a part of something that wasn't right. That's real."

Ali's principled stance also made him a hero to many -- an icon of courage and black pride. No wonder the fans in Zaire adored Ali, seeing in him a symbol of the struggle against oppression. Mobutu had brought the fight to Kinshasa by offering a guaranteed purse of $5 million for each fighter. There was also an "African Woodstock" organized in conjunction with the bout featuring performances from the likes of the Spinners, James Brown, B.B. King and others. But it was Ali's attempt to regain his lost title that gave the event its drama.

"When George Foreman came to Zaire, he came with his pet German shepherd," recalls Bingham. "That was a no-no because it was a reminder of Zaire's colonial past where the police kept the crowds in line with German shepherds. So they hated him. But they loved Ali. That's why the crowds would always chant, 'Ali boma-ye!' which means 'Ali, kill him!' It was wonderful seeing the feeling they had for Ali. It was a lot of fun just hanging out."

"I would add that to know George Foreman now is to know an entirely different man. But at that time, he was a big brute."

In fact, Foreman was heavily favored to win the fight. ABC commentator Howard Cosell predicted Ali's loss and subsequent retirement, and he was not alone in believing that the younger Foreman would destroy Ali, then 32. But the experts were dead wrong. Using a technique he called "rope-a-dope," Ali allowed himself to be pummelled by the 25-year-old champ. When Foreman tired, Ali fought back, knocking him out in the eighth round. It was a stunning victory. Yet the fight itself is only a small part of the large exhibit.

"People know I'm not a fight photographer," says Bingham. "I'm Ali's friend, and I was always nervous for him. When he got hit, I got hit. So it was hard for me to watch."

Bingham was more successful at capturing the spectacle that surrounded Ali's eight-week stay in Zaire. There's a young, vibrant Don King courting the press with a smile and a handshake. There's the press itself, including writer-celebrities like Mailer and George Plimpton, as well as correspondents from all over the world. There are Ali and Foreman's training camps, and even a photo of Ali spying on Foreman with one of Bingham's cameras. And there are the Zairian people -- sometimes dancing in colorful garments, other times cheering on their idol Ali in huge, smiling masses.

Ali and Bingham met in 1962 while Bingham was a cub photographer for the Los Angeles Sentinel, one of the largest black newspapers in the country. Bingham was given the assignment to cover Ali, then Cassius Clay, who was in town for a fight. Later, when Bingham spotted Ali and his brother scoping chicks on a corner in downtown L.A., he offered them a ride. They've been pals ever since.

"I made Ali through my photographs," he laughs. "No, think about it, Ali's the most recognizable face on Earth. Me, I love meeting people. I love seeing the world. It's been one hell of a ride. Going here, going there. Meeting all these so-called big shits, little shits. It's been wonderful. I have the best job in the world. No one gets to do what I do."

"People call me his personal photographer, his friend. After the fights, it would always be Ali and I and his brother. Today it's Ali and I and his wife. Sometimes just Ali and I."

The friendship is genuine, but so is Bingham's talent. Indeed, both factors may help explain the long association. Bingham is a great photographer who needs a larger-than-life subject. Ali is a colossal figure who requires a photographer nonpareil. In each other, they've apparently met their match. And the Fowler Museum's exhibit offers ample evidence to this effect.

"Actually, I've told each of his wives that I was here before you came," says Bingham, smiling. "And I'll be here when you leave."

Shares