Believe it or not, James Bond had a childhood. In Ian Fleming's "On Her Majesty's Secret Service," the seaside promenade of Royale-les-Eaux reminds Bond of "the velvet feel of the hot powder sand ... of the swimming and swimming and swimming through the dancing waves -- always in those days, it seemed, lit with sunshine -- and then the infuriating, inevitable, 'time to come out.' It was all there, his own childhood, spread out before him to have another look at. What a long time ago they were, those spade-and-bucket days! How far he had come since the freckles and the Cadbury milk-chocolate Flakes and the fizzy lemonade."

I, too, had a childhood. There was lemonade and hot powder sand and all the usual stuff. But it ended in 1979 -- the same year I discovered 007 and his license to kill. I was 12, desperate for pantyhose and fuzzy velour shirts, enamored of white roller skates with shiny blue wheels. After school, I used to throw myself down in the small space between the back of the couch and the stereo, turn the Kinks up loud and read about James Bond. I started with 1953's "Casino Royale," Fleming's first novel, and barreled my way through "Doctor No," "You Only Live Twice," "The Spy Who Loved Me" and all the rest.

James Chapman, author of the smart new book "Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films," points out that reviewers have largely reviled Fleming's novels as sadistic, sexist schoolboy fantasies. The majority of literary critics locate the books' appeal in their propagation of an ideology of almost imperialist British supremacy. And Chapman himself notes that the irony and humor in the character's film incarnation are noticeably lacking from the books.

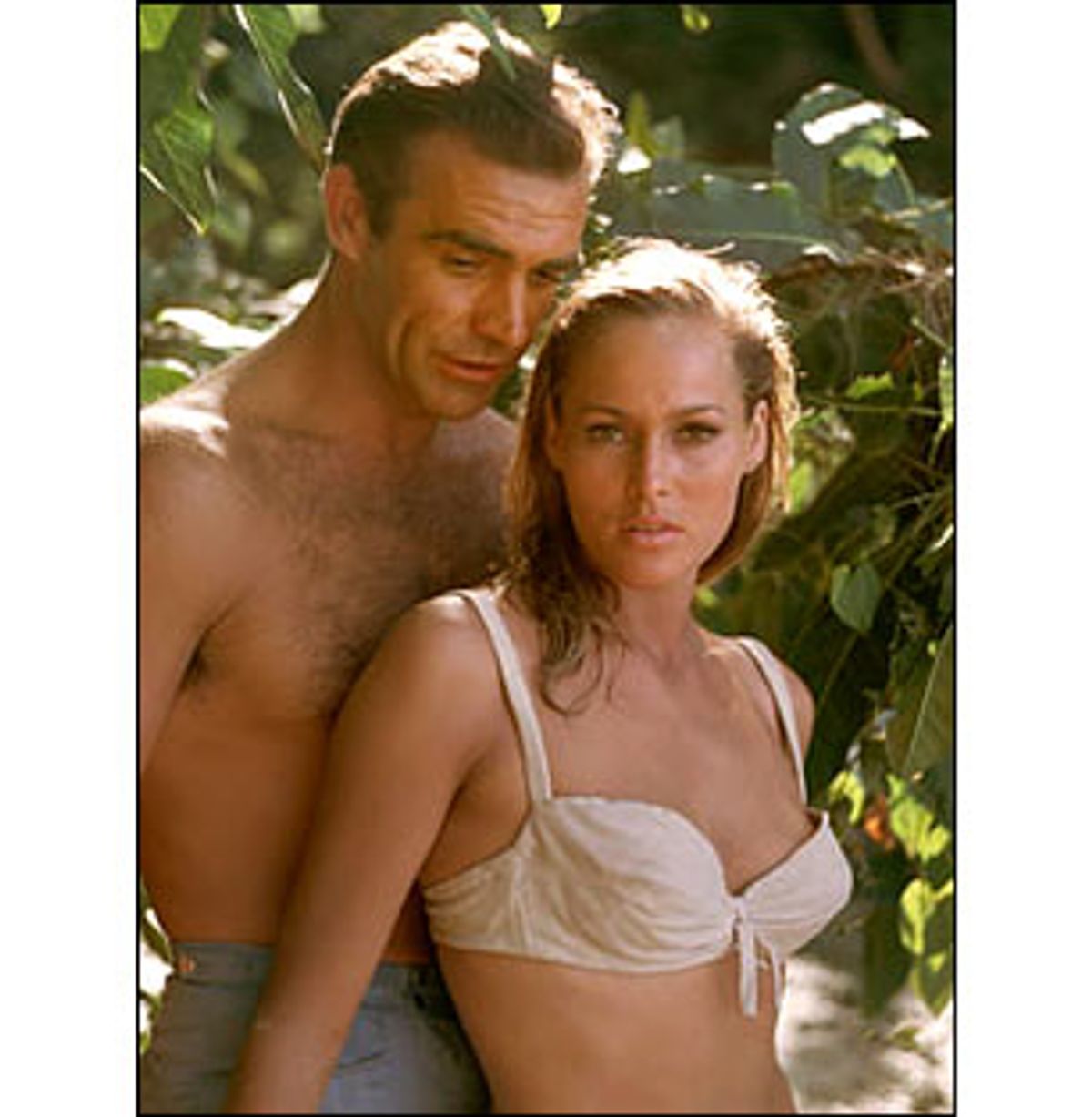

Why then, would an American preteen girl (whose other favorite authors were Judy Blume and S.E. Hinton) read Fleming? I didn't like other espionage novels. International politics bored me silly. The books weren't funny, and by all rights I should have been alienated by what critics call their voyeuristic sexism. For example, Honeychile Rider, the heroine of "Doctor No," playfully throws her naked body against Bond as they stew in the villain's luxury spa/prison. "Honey," Bond tells her, "get into that bath before I spank you." She obeys, pouting, "You've got to wash me. I don't know what to do. You've got to show me." Infantilized, stupidly ignorant of the danger of her situation and as horny as hell, Honey epitomizes all that any budding feminist should detest.

Nonetheless, sex is interesting to an adolescent girl, whether it's sexist sex or not, and certainly Fleming's eroticism was part of the books' appeal for me. The author once said that the target of his stories lies "somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh." Still, I don't think the relatively infrequent moments of nudity and arousal would have been enough to make me love James Bond novels if the heterosexual male gaze were really as pernicious and pervasive as the critics say -- and as it is in the movies. The films portray the dominant Bond, if not the definitive one, and it's hard for most people to read the books without images of Sean Connery or Pierce Brosnan in their heads. And in the movies, Bond is a hypermasculine spy whose lustful eyes rove over bodacious female bodies, filmed through the vehicle of a camera that does likewise.

In contrast, Fleming is an equal-opportunity voyeur -- a point lost on most critics. His sensual catalogs of men's bodies easily equal those of women's. An example, from "Thunderball": "In contrast to the hard, slow-moving brown eyes, the mouth, with its thick, rather down-curled lips, belonged to a satyr ... the muscles bulged under the exquisitely cut shark-skin jacket. An aid to his athletic prowess were his hands. They were almost twice the normal size ... Largo was an adventurer, a predator on the herd."

In "From Russia With Love," SMERSH's psychopathic head executioner is receiving a massage. The masseuse tries to analyze her "instinctive horror for the finest body she [has] ever seen" as she rubs him in the sunlight by a pool: "She poured about a tablespoon full [of oil] on to the small furry plateau at the base of the man's spine, flexed her fingers and bent forward again. This embryo tail of golden down above the cleft of the buttocks -- in a lover it would have been gay, exciting, but on this man it was somehow bestial ... she shifted her hands on down to the two mounds of the gluteal muscles." The description lasts for four pages.

Fleming also describes cars and meals with much of the same erotic charge. In "Secret Service": "A low white two-seater, a Lancia Flaminia Zagato Spyder with its hood down, tore past him, cut in cheekily across his bonnet and pulled away, the sexy boom of its twin exhausts echoing back from the border of trees." To Bond, a pair of exhaust pipes is as sensual as a dish of crabmeat, which is as sensual as a pair of breasts.

Another thing I liked about Fleming's Bond back in those days was his vulnerability. He's not the unflappable, historyless dandy of the films, but a man with a childhood, a heart several times broken, a body covered in scars. On-screen, as Chapman points out, snobbery was an essential part of the Bond character. When Connery picks up a champagne bottle to use as weapon in the first film, Doctor No remarks, "That's a Dom Perignon '55; it would be a pity to break it." Bond, ever the aesthete, replies, "I prefer the '53 myself." But in the books, he is neither so particular nor so educated about his pleasures. He is a sensual man and smokes a particular brand of cigarette, but he's as likely to drink a gin and tonic or a glass of bourbon as the famous "vodka martini, shaken, not stirred." In the Bahamas with American sidekick Felix Leiter of the CIA, it isn't Bond who objects to the watered-down gin in the casino martinis; it is Felix. He gives a lengthy diatribe on the shifty economics of hotel bars, sends the drinks back and advises Bond not to let himself be taken in. "I always knew one got clipped," Bond says in astonishment, "but I thought only about a hundred per cent -- not four or five."

Fleming's Bond is often frightened. Though you never see it in the films, the text tells us his heart is pounding in fear, his breath sounding in his ears: His "stomach crawled with the ants of fear and his skin tightened at his groin." Rather often, too, he is embarrassed or emasculated. For example, when "pimping for England" in Russia, he wonders whether the defecting spy he makes love to in exchange for an enemy cipher device has found him too rough in bed. Near the end of "You Only Live Twice," he is an amnesiac living in a Japanese fishing village, frustrating Kissy Suzuki because he has forgotten "how to perform the act of love." (Never fear: She solves the problem by buying him a pillow book, and -- virility restored -- Bond begins to remember that he is a superspy.)

In "Doctor No," Bond is nervous about keeping his job, having flubbed his assignment in "From Russia With Love" by failing to recognize an obvious trap and by losing a fight with an elderly woman who injects him with nerve poison. Physically depleted, Bond is given a minor job investigating a personnel problem in Jamaica because M. feels it will allow the spy to get some R&R. In "Thunderball," he has once again been judged weak by the Secret Service and is forced by M. to renew himself in a spa, dining on weak broth and submitting to numerous physical examinations: "He had a permanent slight nagging headache, the whites of his eyes had turned rather yellow, and his tongue was deeply furred. His masseur told him not to worry. This was as it should be. These were the poisons leaving his body. Bond, now a permanent prey to lassitude, didn't argue. Nothing seemed to matter any more but the single orange and hot water for breakfast."

Though he'll call a woman a bitch and doesn't hesitate to forcibly kiss his massage therapist, Bond is still a sensitive guy. He is unbribable, says SMERSH's dossier, but has a weakness for the ladies. On-screen, that weakness translates as a strong sex drive and roving eye, but in the books it is his genuine failing as a spy -- a susceptibility, an almost needy urge, to drop everything for love. "Your brother was killed by Largo, or at least on his orders," he tells Domino, the Italian mistress of the villain with the giant hands. "I came here to tell you that. But then ... you were there and I love you and want you. When what happened began to happen I should have had the strength to stop it. I hadn't." After she saves his life in an underwater battle, he awakes, weakened and disoriented, in a hospital room. All he can think about is Domino, and the book ends with a cuddle: He finds her in a neighboring ward and collapses in exhaustion on the rug beside her bed, "with his head cradled on the inside of his forearm."

Of course, Domino is gone and forgotten by the start of the next novel, but the point is that Bond's character features the alluring mix of hard and open that typifies the heroes of romance novels. He's not a womanizer in any calculated way: He feels a rush of emotion, lust and affection when a woman touches any of his few soft spots; he tries to protect whoever it is, but she usually rejects his efforts and rescues herself (as Honey and Domino both do) or rescues him (as Domino and Kissy do).

More important, the Fleming novels do something the films cannot possibly do: They put us inside Bond's body. We're not looking at the well-dressed Timothy Dalton driving a sleek car through an action-packed chase; we're in the driver's seat with Bond, with his aching head and multiple scars, his stomach tightening with the ants of fear, his job on the line because of some recent failure and part of his mind on a woman he'd be better off leaving alone. Fleming lets us in, and the movies do not.

When I read those books in seventh grade, I was James Bond. They elicited in me a kind of transvestite empathy that transcended whatever unarticulated problems I may have had with their politics or values. Bond is the spy of all spies not because he's the hero of the most popular film series ever made, not because he knows what to drink, loves 'em and leaves 'em and never bats an eye, but precisely because he does not do these things. Before I moved on to "Still Life With Woodpecker" and "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy," Bond gave me a sense of the mysterious anxieties of the macho psyche -- something I urgently wanted to understand.

Shares