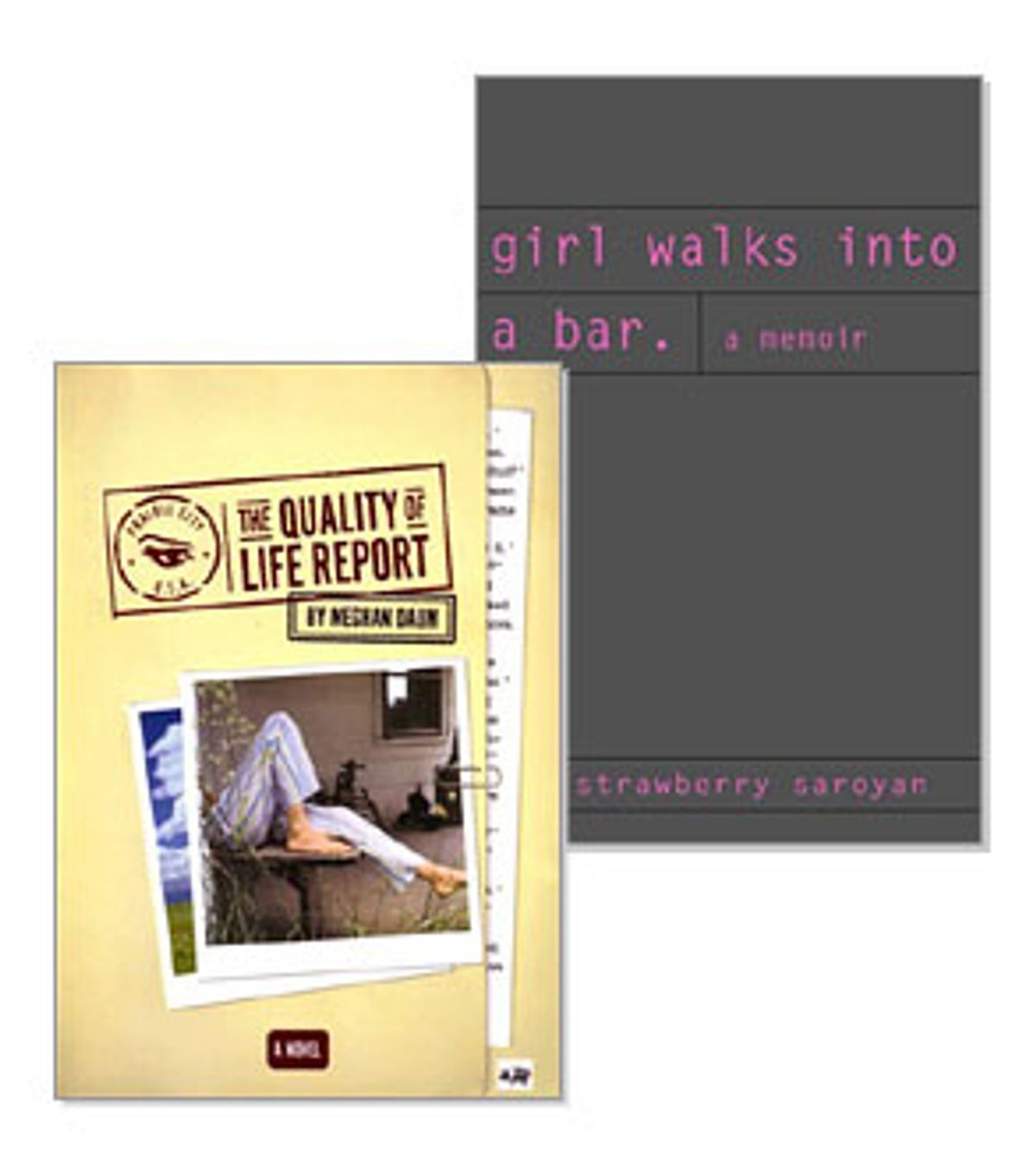

Meghan Daum seems aware that by now the last thing people want to read about is what it's like to be single in New York, or at least, the New York life we find in single-gal books. Just 37 pages into Daum's first novel, "The Quality of Life Report," her 29-year-old protagonist, the morning-show reporter Lucinda Trout, flees Manhattan. It's goodbye to Jimmy Choo'd women, East Village romance and a torturously confining apartment. We readers, who briefly despaired we'd be stuck in the narcissistic netherworld of bad first dates, soulless jobs and sob stories about Manhattan studios, can breathe anew.

We're off with brave Lucinda to Prairie City, Neb., where Botox and $20 power yoga classes may exist, but have not yet become self-mocking clichés. (Personally, I hope to never write the words "Botox," "East Village," "single" and "apartment" ever again.) If we've become collectively, deliciously drunk on "Sex and the City," then Daum's novel feels like the first steady hour in the afternoon, after we shake off our hangover.

The very act of leaving New York, it turns out, is as inspiring as striving to get there. Daum, lest we forget, did it herself. Her wonderful collection of essays, "My Misspent Youth," included a well-known New Yorker piece of the same title in which she detailed how her supposedly bare, writerly lifestyle spiraled into financial ruin. Daum had no choice but to leave; financially she had to seek cheaper pastures. Yet something else in the essay signaled that it wasn't just money that nudged her over the George Washington Bridge and all the way to Nebraska. (After all, New Jersey's right there, with more manageable rents and a handy PATH train that trundles you right back into the West Village.) No, Daum, one senses, was also a bit tired of New York, and maybe, since New Yorkers see the city in themselves and themselves in the city, a bit tired of herself.

When I first read her essay, I'd just moved to Manhattan and was horrified that she was scrapping what sounded like the perfect life for one in Nebraska, of all places. Now, after four years of working in the city and ever more daydreams of moving somewhere far, far away, I read "My Misspent Youth" and "The Quality of Life Report" and it all makes beautiful sense. The thrilling experience of being young in New York can also send you to depths of misery previously unimagined. Is it being young or is it New York? Is it feeling inadequate and small among so many successful people and tall buildings? Who knows, but at times, leaving the city behind seems the only solution.

When Lucinda makes it to Prairie City, "The Quality of Life Report" opens up like the plains of the Midwest -- in short, it quickly gets better. The novel is smart and funny, and it's one of Daum's talents to write remarkably about what her narrator observes, rather than moaning on about her messy innards. Lucinda buys a house in P.C. and falls in love with someone who is much more complicated than she recognizes at first. She messes up, offends people, goes to tanning salons.

Daum describes Lucinda's irresponsible drug addict boyfriend Mason this way: "Prairie City was for him, as it was for many of its citizens, a place in which the margin of error was as wide as land and sky itself." In New York, on the other hand, "we were packed so tightly and moving so rapidly that one misstep could knock us permanently off course. We always seemed an instant away from losing everything." So there's something hopeful, and also perfectly reasonable, about the image she leaves us with in the end -- that of a colt kicking his wayward legs, with open space to fall down, and more space to get up, try again, keep running. By that last page, I suddenly realized that Daum had traveled halfway across the country and actually gotten somewhere.

Strawberry Saroyan packed up the getaway car much sooner than Daum or her fictional alter ego, who remained in New York into their late 20s. Saroyan took off at 25. In her collection of essays, "Girl Walks Into a Bar," she details life as a 20-something Manhattan media girl on the make, a 20-something single girl making her way through the bar scene and then, later, a 20-something media girl on the make in L.A. (and making her way through the L.A. bar scene.)

Saroyan's is a book for a narrow audience; I can't imagine that my friends who work in banking or at nonprofits or who go to medical school will relate to a memoir about the fantasy world of New York glossy magazines. Moreover, it's a book about Saroyan's fantasy of the experience that fantasy world would give her. I'm pretty sure there are many women who work in the Condé Nast building who think that what they do is just a job, not a life.

But when you're young it's easy to get the two confused. Saroyan had a "vague fantasy about being part of a media 'power couple'"; she delights in seeing a particular Elle magazine headline, "Enter the Era of Elegance"; she believes that magazines possess some mythical power to transform. When you're reading "Girl Walks Into a Bar," Manhattan seems like a very silly place, cluttered with so much stuff that it's hard to see your way around the corner, especially when you're naive and ambitious.

Saroyan tends to ramble on without much insight, spending four pages discussing an insignificant flirtatious encounter. She begins too many sentences with "And" -- "And then he said, 'Hi.' And that actually is all I remember him saying in those first minutes, but it was enough" -- for dramatic effect. While the flirtatious encounter obviously was dramatic to her then, one senses that it shouldn't be now.

We get less a picture of Saroyan's New York or L.A. experiences than an X-ray of her emotional makeup, and in a book where little more is happening than working and going to parties and flirting with guys and fighting with girlfriends, this overanalysis becomes tiresome. Sometimes the book engages your most self-absorbed parts, the parts you expect (or hope) will wither away and die with age. Mostly this is because Saroyan still seems preoccupied with things that are frivolous; the book is devoid of concern about anything bigger than herself and what's 5 feet in front of her. Often, her book filled me with utter despair.

But that's because Saroyan also gets a few things incredibly right. Saroyan is writing about a greater malaise, one more clearly evoked by Joan Didion in her 1967 essay "Goodbye to All That" (to which Daum's work has been compared). Didion's essay probably feels familiar to anyone, anywhere; she depicts that sudden rush of paralyzing doom, when the simplest event can cause nervous breakdowns on street corners. Yet Didion's distress is particular to New York -- upper Madison Avenue and Yorkshire terriers make her cry.

Saroyan zeroes in on New York as well, in this case, when talking about love: "Of course, fantasy exists in most romance, but I think it is particularly encouraged and intensified in all aspects of one's life in New York. To live in the city almost demands it, for why else would so many people put up with so little space, such high prices, such bitter winters, such feverish summers? ... My real life was my fantasy life, and it would start in, say, five years, maybe less, when I was a big success -- when I was rich, or famous, or both." Eventually, Saroyan feels caught in a permanent state of wanting -- "I was missing my own life" -- exaggerated by living in place that presents so many possibilities.

It's clear that "Media Land," as Saroyan calls it, also plays a large part in the creation of this fantasy. (One of the best things about New York, anonymity, isn't such a prize in an industry where success and your self-esteem depend on how often your name is in print or on TV.) Daum's Lucinda Trout works in the media as a lifestyle correspondent, "covering the toe ring craze and announcing to New Yorkers that 'scones are the new muffin.'" When she is deciding whether to leave, it's a magazine headline that sends her over the edge: "What would happen if I removed myself from the crowds and the money and the constant talk of who had been featured in articles in New York magazine with titles like 'Under 35 and Over the Moon: Gen-X Internet Moguls Cash In and Take the Real Estate Market by Storm'?" After a while, that stuff will kill you.

What's interesting about Saroyan is that Media Land wore her out so fast. Like Didion, she came to New York from the West Coast. She left at only 25 after a stint as an associate editor at Condé Nast Traveler and some freelance work, after morphing into a well-dressed, high-heeled career woman, finally attending the parties of her dreams, fully joining "the world created by the glamour-creators for themselves." Her photo appears in the New York Times Style section and she feels she has arrived: "So you begin living a public life, a life whose values are defined by other people, by media people, by, finally, media itself, even though you aren't famous."

This is an idea that Saroyan circles again and again: Young women take certain cues from the media and classify themselves accordingly, usually to their own profound disappointment. Imagine working within the media, where they hatch an idea like "toe ring craze" and infuse it with mind-altering importance and seriousness. To try to live up to mandates of "crazes," "moguls" and "under 35" is completely exhausting. It was those kinds of intentionally vapid magazines, of course, where Saroyan got her ideas about New York and happiness in the first place.

But in talking to friends who spent their 20s in other places and in other occupations, one thing seems clear: The 20s are a weird time. It was a considerably insecure time for my mother, who got married at 22 and had children in suburban New Jersey; and it was a hard time for my 40-year-old friend who spent her 20s unmarried and working in Boston. Didion acknowledges this: "Of course it might have been some other city, had circumstances been different and the time been different and had I been different, might have been Paris or Chicago or even San Francisco, but because I am talking about myself I am talking here about New York." Indeed, even when Saroyan leaves New York and continues life in Los Angeles, she can't seem to shake her dissatisfaction.

So, it seems these women's sudden unhappiness is less about New York and more about the end of a period you spend looking forward to something else. Suddenly, you're ready to accept that life has begun; and that psychological shift sometimes necessitates a geographical one as well. A question about "Girl Walks Into a Bar" remains: Had Saroyan succeeded by the standards of Media Land, had her life moved forward in the way that she once desired -- with a powerful media boyfriend, a top-rung magazine job and a vast apartment -- would she have stayed in New York? It's possible, but the reality is that Saroyan looked in on the party and found it sad.

Still, as satisfying as it may appear to reject the most powerful, glamorous place in the world (before it rejects you), it can also feel like a cataclysmic decision. After all, in the collective imagination of people from a certain class background and/or a certain educational level, New York is where you're supposed to make it. If you grow up thinking that New York is what you work for, to leave is almost to admit that you have stopped dreaming. It seems like an admission of failure. But actually, as both Daum and Saroyan show, like any other major life decision, it's quite brave. What's unsettling about "Girl Walks Into a Bar" is that you're left feeling as if Saroyan's fantasy haunts her. She's still not quite comfortable with her real life.

In "Goodbye to All That," Didion writes, "It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city for only the very young." But sometimes I wish that I'd faced New York when I was at least 30. New York doesn't seem so scary to the well-adjusted and professionally secure 30- and 40- and 50-somethings I know. They run marathons, have babies, go to the movies alone. They go to fancy parties once in a while, but most nights, they're at home, reading or writing or playing with the kids or just watching an old movie with some takeout Chinese. A friend once said to me that she didn't feel happy in New York until she could stay home on Friday nights and watch videos without getting that unsettling itchy feeling that she should be doing something else. I wonder: If Saroyan had just stuck it out for a little longer, would she have realized that, among many other things, New York is a great place to watch TV?

Shares