I met Helen Knode in 1989 at the L.A. Weekly, when she was in the middle of her six-year run as the paper's leading contrarian film critic. I had just come to town from New York and an editing job at the Village Voice, and was pretty much on my own. Helen and I became fast friends. We shared a love of feminist discourse and enjoyed healthy disagreements over Indian food: While Helen, a Calgary cowgirl, studied early matriarchies, I barely tolerated the notion of "goddess" unless applied to Madonna. She didn't tolerate Madonna. Nevertheless, when my Los Angeles stay was cut short and I returned to New York, we resolved to stay in touch. In 1991, Helen married crime writer James Ellroy and quit the Weekly. Relocated to Connecticut, she was back in my sphere. But after four years, the couple made for Kansas, where Helen had graduated from college years before; it was there that she set herself up to write her first novel.

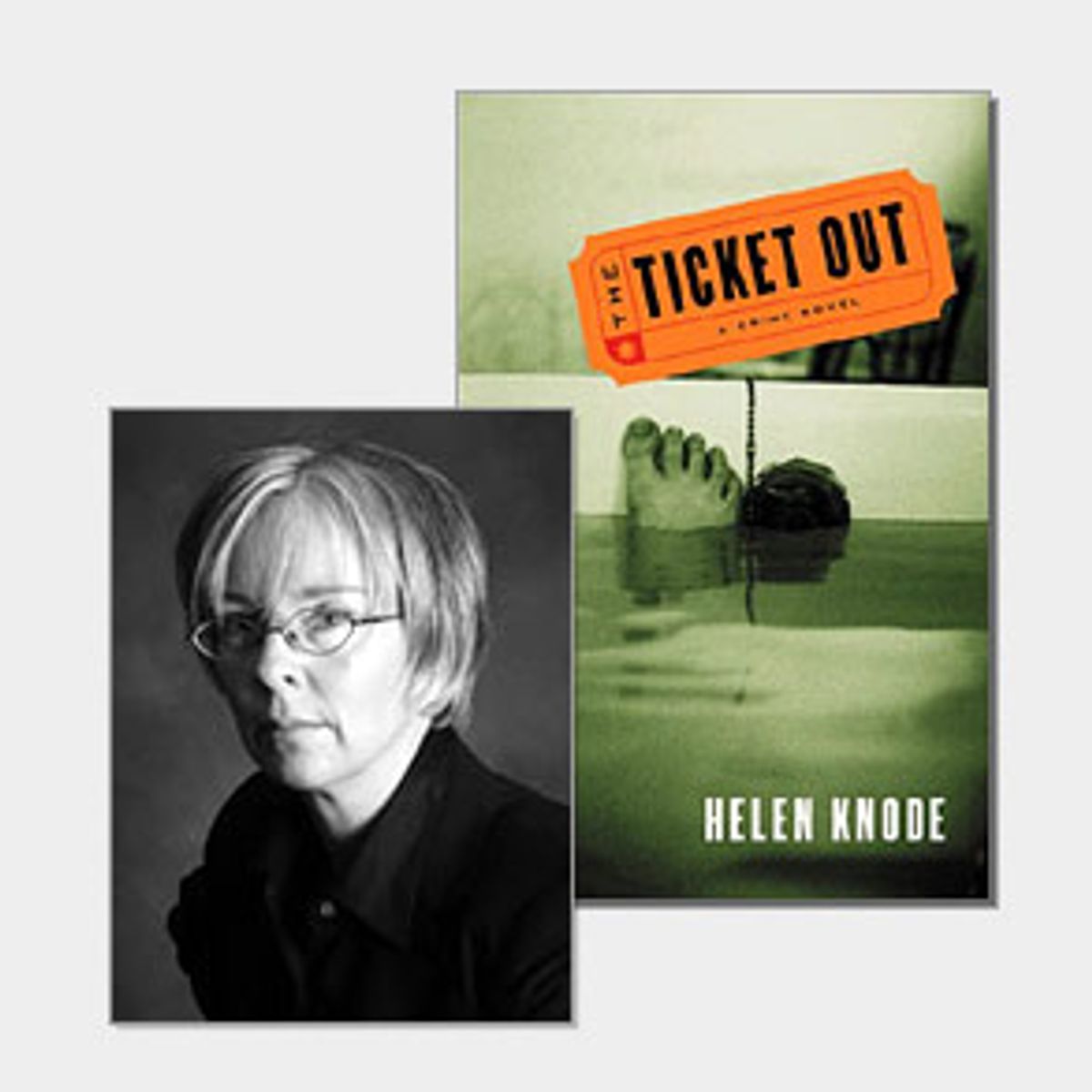

Eight years later, Knode, now 45, talks about that novel, "The Ticket Out," and the "media-addled, frustrated career woman" who drives her unique crime story. After disillusioned film critic Ann Whitehead finds a dead woman in her bathtub, she embarks on a journey to discover more about the woman and hooks up with the main detective whose job it is to solve the crime. Along the way, she unearths and becomes embroiled in a larger scheme that unites old Hollywood decadence with the corruption of contemporary L.A. Written with wiseacre wit and stylish yet clean storytelling, "The Ticket Out" is an engaging romp with plenty of ideas jostling for place among the many characters and plot points. From a temporary house on the Monterey Peninsula of Northern California, minutes from the new house being readied for her and Ellroy, Knode reports that the book was "a crushing intellectual and completely wrenching emotional labor."

Give me the basic plotline of "The Ticket Out."

It's a police procedural, a homicide investigation. Ann, my heroine, an amateur, finds a dead body in her bathtub. She's fascinated not with the crime so much but the life: Who is this woman? And she runs up against the LAPD detective who is investigating the crime, and gets involved in his investigation too.

Greta is the dead woman and Doug is the detective. So describe the subsidiary plotlines.

There is the Oedipal plotline, which involves Ann Whitehead's father and sister, and their presence in L.A. There is the fact that the dead woman has written a script that is missing, and the script is the story of a real unsolved murder -- real as in an actually historically true, unsolved murder of a woman named Georgette Bauerdorf who was murdered in October 1944 in West Hollywood. The crime has never been solved.

What are the central themes of the book?

Hollywood, and the women in Hollywood. There's a running argument about the state of movies and of film criticism and of Hollywood. Everybody Ann talks to has some role in Hollywood, whether it's fringe or central. And there's also the running theme of Hollywood's past. I use Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the greatest studio ever from the classic era of Hollywood, as a symbol of Hollywood's greatness. There's lots of stuff about Louis Mayer and Irving Thalberg and the MGM lot, which is now owned by Sony.

And there's a lot of stuff about women. Women in various roles in the movie industry, in front of the camera, behind the camera -- the women who never made it, the women who slept their way to the bottom.

And you might also say that there is a subplot and a theme about police and authority.

Yes. Absolutely. Thank you for noticing that.

And concurrently about violence.

Violence against women. Violence in general. The breakdown of authority. Specifically male authority. I'm always looking to shock, and I thought the most shocking thing I could do was try to put myself in the place of the LAPD. Because I really do believe that we live in a time of an authority crisis. And the police are blamed for things that aren't their fault, exactly. They're subject to the same crisis of authority as everybody else, even though they're supposed to be authority. And so I have a lot of male "authority figures" who are weak or stupid. The father, of course, being the ultimate authority figure. All these different kinds of authority and power centers, and they've all just collapsed.

The ultimate irony is that you have your heroine fall in love with a cop.

Well, no, no. Did I say she was in love? Did I say that?

You did not.

[Laughs.] She slept with him. That's all. That's all that's happened so far. One of the questions I started the book with was: What produces a hard-boiled woman? When men are hard-boiled, they're hard-boiled for specific reasons. A woman gets hard-boiled because of sexual trauma, because of abuse in the past, because ... she's like Scarlett O'Hara. She looks at the world, it's a man's world, and she grows a shell. So this was my version of doing a hard-boiled woman. Without it being a completely unanalyzed hard-boiled woman.

What was the initial spark for "The Ticket Out"?

I had started writing a column for the L.A. Weekly called "Weird Sister." It was a creative leap for me, because it wasn't reviewing movies. I could write about whatever I wanted to write about. Then I met James [Ellroy], whose work I did not know when I met him, and he was telling all the unhappy journalists who talked to him to write a novel. One thing led to another and I was suddenly married and moving to Connecticut. I was going to continue the column but I realized it wasn't enough.

I should also mention that when I was a columnist I wanted James to take me around and show me Black Dahlia sites. I'd never heard of the case [a notorious Los Angeles murder from 1947], but I read his book ["The Black Dahlia," 1987] and was so impressed by the way he treated Elizabeth Short [the murder victim] that I started thinking about violence against women differently. Because the normal feminist discourse on violence is that we are the objects of violence, we are the victims of violence.

Right. And of course most murder victims in crime books seem to be women.

Yes. So what does that mean for the women who are living, who have managed not to be killed? What is it like not to be the object of violence but the subject of violence? And I find that in many mystery novels and crime novels written by women, they act like it's the same thing for a woman to find a woman killed as it is for a man to find a woman killed. But for me, any woman who finds a woman who has been murdered, it's got to throw you back on yourself: Why is she dead while I'm alive? So I went into the novel with these two questions in my mind: Why are movies bad and how do women get dead? And it somehow ends up being the same answer. [Laughs.] I don't know what the answer is but I'm sure it's connected. [Laughs.]

Why Hollywood?

Well, I was there. I obviously consider it important for a certain period of my life. When I first started at the job I really just thought I was hotter than shit. Even though the L.A. Weekly is definitely fringe, and never aspired to be part of the industry. But you're close to that energy, and you feel it all the time and it's pumping a little into your veins. It's a kid thing -- to take your energy from something like that.

I finally realized after two or three years that there was some profound philosophical bankruptcy in what I was watching. I myself became unhappy and started to feel empty, started to feel like this wasn't giving me its energy anymore, and wasn't reflecting what I believed. Not just on the women front. You know, you can criticize the movies for being sexist, for sure. But just in terms of a degraded view of human possibilities, of human behavior.

So to feel that kind of loss and disappointment you must have had very high hopes for the movies to begin with.

That were completely neurotic. [Laughs.] I mean, why do people look for meaning outside of themselves? It isn't there. I had a tremendous amount of psychic energy invested in movies: Movie history and sexy movies and art movies. Movies are stupid. They're not reflecting anything in particular, except for maybe the end of civilization. [Laughs.]

Is the nasty old mogul Joel Silverman in your book really based on [late MCA head] Lew Wasserman? One of your reviewers suggested you had to wait to publish your book until Wasserman died, as if he might have sued you for defamation of character. Does that have any basis in reality?

Absolutely none. Lew Wasserman was at one time the most powerful person in Hollywood and continued to be a presence up until his death.

And did in fact ruin movies.

He didn't ruin them. He didn't care about them. That's the whole thing. What people don't really understand is Hollywood is run by a lot of people who don't care about movies. They're just making money. And they use that money, like Mike Ovitz, to buy beautiful art collections. [Laughs.] But no, I mean, Joel Silverman is just a type.

Where did Greta come from?

She came from my meeting with [film director] Kathryn Bigelow. But she's not Bigelow. I'm a big fan of Bigelow's. I interviewed her for "Blue Steel." That was in '89, years before I started this book. I think that what Bigelow wants, which is to be a female director of action, is strictly speaking impossible, given Hollywood's gender categories. My heroine is driven crazy by this contradiction. She wants to be Steven Spielberg, she wants to make widescreen adventure movies. Her existential position in Hollywood just fascinated me. How could she do the things she wanted to do? I have felt it myself. It's not just Kathryn Bigelow, it's women who just want to do what they want to do. And there's some reason that the world won't let them. At that time, you know, Bigelow had not made "K-19: The Widowmaker."

Let's talk about "Thelma and Louise" for a moment.

"Thelma and Louise," which I think is a watershed, is the tragic view of the condition of women. You just drive off a cliff and you're dead. Because you've been cornered and there is no hope. You cannot be free. You can drive somewhere and not have a history. You can drive somewhere and start new. Just like the myth of the Wild West. There's a frontier where you can be free. And for women there is no such place. Because wherever you go, you are a vagina. Wherever you go on this planet you are a vagina. And that's what happens, that's the dynamic. That's what starts "Thelma and Louise." Thelma and Louise decide they want to take a vacation from their thankless husbands and boyfriends. So they jump in their car, they're going away for a weekend. The first thing that happens is they go to a bar for some fun and someone gets raped. Or it's attempted. And so someone gets shot. And they're on the run.

I know the movie took a lot of flack for being anti-feminist and anti-woman, that women with guns are just as bad as men with guns. But the dynamic, the thing that's motivating the violence, is purely female. I was very moved by that movie, and I wanted to go on in that vein. What does it mean for a woman to be free?

Has anybody come close to making a movie that touches on that issue since then?

I don't think people have even tried. What's come out of "Thelma and Louise" is this whole kicking-feet genre, like "Charlie's Angels" and "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" and "Lara Croft: Tomb Raider" and all the chick-flick stuff. These movies have skipped over the problem of freedom. I have not seen anything like "Thelma and Louise," because it's not explicit. It's talking about its problem in genre language. It's not directly saying what it's saying.

What was the last good movie you saw?

"Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone." [Laughs.] I'd rather watch 15 Harry Potter movies than "The Hours."

Tell me about "The Hours."

I think the basic premise of "The Hours" is that modernism is responsible for AIDS. [Laughs] It's a chain of unhappy women leading to a guy who throws himself out the window, all with the link of "Mrs. Dalloway." Virginia Woolf walking into the river leads to him throwing himself out the window. Any movie that opens with a woman walking into a stream with rocks in her pocket is not my kind of movie. And it all seems to be this morass of psychological opacity and sexual ambiguity and unhappiness. It's the most morose movie I've seen in a long time. Nobody knows anything, everything is lost, everything is despair, everything is unhappiness and water's rushing over your head.

Not that there's not tragedy in life. But if I'm going to watch a tragedy I'll watch David Lean, you know. I'll watch "Doctor Zhivago" if I want to cry. At least that's a clean cry.

What about "Adaptation"?

I didn't hate it, but again it's one of those movies that seems to say that there are only two options for human consciousness. Either completely paralyzed self-consciousness, which is not even the same as self-awareness, or your other option is bloody, low-chakra, base, animal unconsciousness, which is adultery, betrayal, drug addiction, death in the swamp, shotguns and crocodiles and car crashes, and all that. There are other forms of consciousness. There's the spiritual dimension that's completely missing.

Who are your favorite directors?

I don't have any anymore.

What do you think about Martin Scorsese?

"Gangs of New York" was like being in a Hieronymus Bosch painting. In a room with no windows or doors or air. Because there's no tension in a movie with extreme violence. There's no suspense. There is literally nothing that your mind is asking itself, because the only solution to every problem is violence. Your mind is so tired but you're getting a sort of psychic workout because it is like having electrodes stuck on your body and you're getting these physical reactions. But it's not engaging your mind.

So what are you loving?

I am obsessed with romance and men and women and the female principle and the male principle and how in this day and age, romance seems to have turned into something like pathology. Nobody believes in it, and yet people are falling in love all the time. And so my favorite movies are romantic movies. I'm a big fan of "Moulin Rouge." That's a movie I would defend. I think Baz Luhrmann is a romantic searching for a contemporary language for romance. And that's why it's so gothic, that movie, because we don't have a natural language for romance.

So I don't have a director anymore. It's more subject matter and view of the world. I have my pantheon of romantic movies, my female transformation plots, which I love, like "The Princess Diaries," "Miss Congeniality," "Now, Voyager." Then, you know, my pure romantic movies that are always exalting even if they're tragic, like "Doctor Zhivago," "Ryan's Daughter," "Brief Encounter" and "Bridge on the River Kwai," "Titanic." I'm a big fan of "Titanic." I think Jim Cameron is our great poet of the doomed heterosexual couple, for which "Titanic" is the ultimate metaphor. [Laughs.]

Ayn Rand wrote an essay called "The Romantic Manifesto." It's the most influential essay, for me, on aesthetics. She makes a difference between naturalism and the romantic. She defines the romantic as the recognition that human beings have a will and they have the capacity to make their own happiness. She contrasts that to naturalism, which has basically triumphed in our cultural world, in which everything is formless, you can't know anything, you can't make your own destiny, you are just prey to all these forces that you can't control. There is no such thing as human will.

I can look at "The Hours," or, say, "Far From Heaven" -- you're looking at people who can't seem to be happy, they can't seem to exert themselves, they can't even seem to say happiness is possible and they will actively work towards it. I'm not a pessimist. So I don't believe everything is darkness and shit and then you die.

Do you think that that's the worldview of classic noir, what you just said?

Absolutely. That we're the prey of these corrupt institutions. They can't be understood, they can't be combated. Essentially, it's just darkness.

Darkness with no hope?

With no hope. And your exaltation is the dark exaltation of flushing your life down the toilet for a woman. And Lord knows they wrote some sexy stuff and made some sexy movies. But I am an optimist and I believe in hope and I believe pessimism is both cause and effect when your worldview is naturalistic.

Why did you use the noir genre then?

I wanted the hard-boiled voice. But I call it "feminist noire," with an "E" on the end.

Why is the last word of the book "Doug"?

Because I have embraced my nature as a romantic. Because the most shocking thing you can be nowadays is a romantic. And that's an ambiguous ending, I hope you admit. And she starts the book dreaming about a gun and ends it on a man's name, after we've had a long soliloquy about why she doesn't love anyone and can't.

It's a message of hope.

It's the lead-in to the sequel.

Shares