It's been more than four years since we watched Shannon Faulkner arrive at the Citadel, that Southern bastion of military maleness, ready to end an era with her presence. There were three years of litigation behind her but only a few days as a cadet ahead of her -- less than a week later, we watched again as she withdrew from the freshman class in tears, leaving her fellow "knobs" to struggle through nine months of hazing without her. South Carolina conservatives heaved a sigh of relief; feminists across the country couldn't help wishing their anointed trailblazer had made a better showing. In living rooms nationwide, we clicked our tongues: After all that, Shannon couldn't hack it.

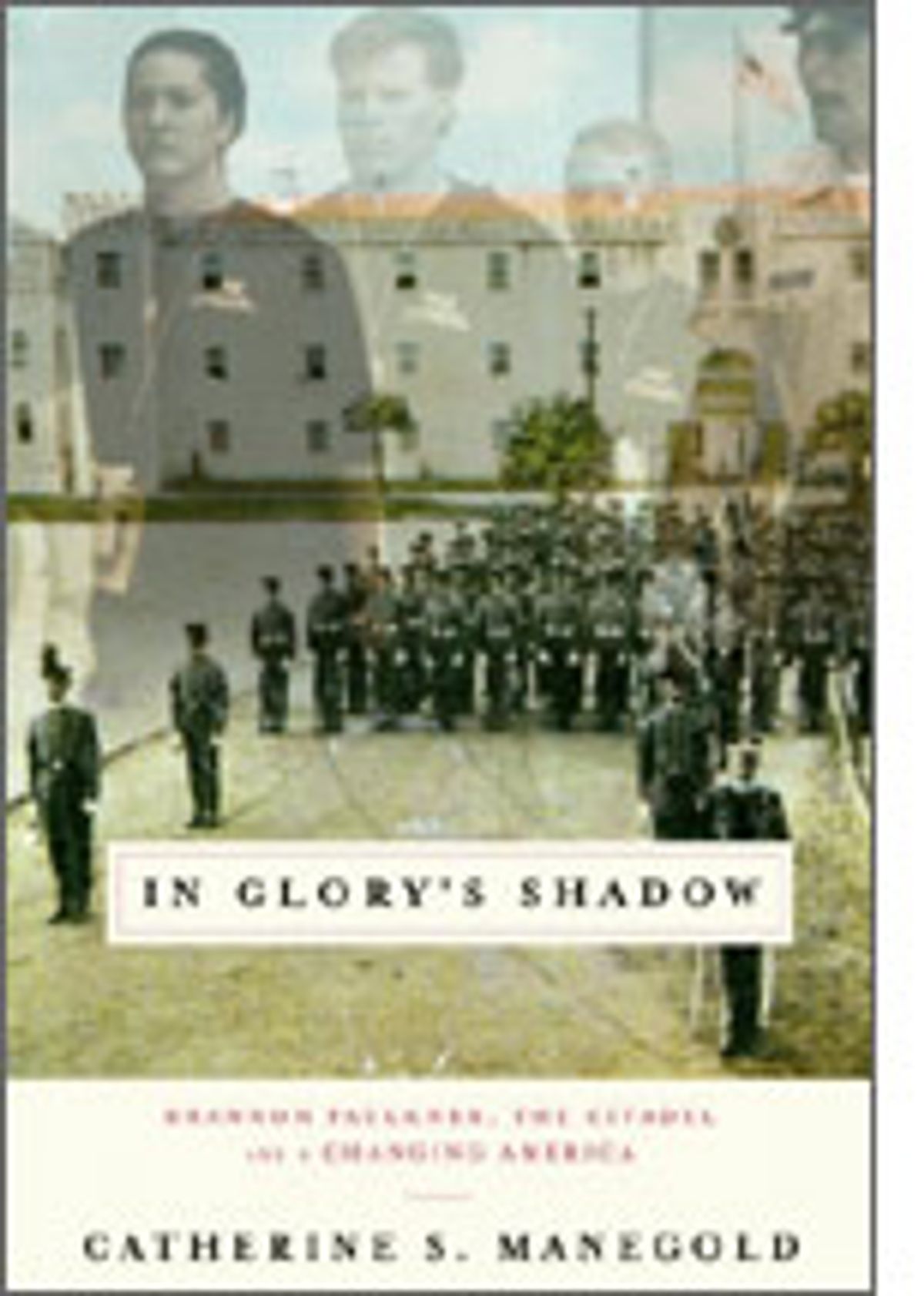

Catherine S. Manegold, who covered Faulkner's legal crusade for the New York Times, doesn't see it that way. To make her case, she goes back to the beginning -- the very beginning. The Citadel was established in 1822 to protect white Charleston from the anger of its own slaves; 20 years later it was reconceived as a school. Manegold spends a third of "In Glory's Shadow" tracing the Citadel's history, from Fortress of the American Way to twisted enclave of sadistic machismo and neo-Nazi paraphernalia. By the time she gets to Faulkner, you wonder not why the girl from Powdersville, S.C., left so speedily but why she set her heart on the school in the first place. By 1995 it was an anachronism, a sealed world of men whose passions sprang "not from what they wanted to preserve but from what they knew they had already lost."

Faulkner's determination, according to Manegold, started from what she perceived as the unfairness of a publicly-funded college -- one better equipped than most in the state -- that excluded women. Faulkner also wanted access to the Citadel's fabled alumni network. Manegold frames the fight as an epic folk tale: "A girl stood up to some old men. What gives you the right? she asked." Nothing, the Supreme Court answered, and Faulkner was in. But once she had won the equal-rights battle, there was still the matter of surviving four years at the Citadel for the dubious reward of membership in a brotherhood of throwbacks increasingly out of touch even with the modern military. When Manegold has finished describing the school's brutal tradition of breaking down adolescents and rebuilding them as men, its falling enrollment and its pathetic academic standards, it's a mystery why anyone, male or female, would want to go there.

Manegold seems to have fallen under Charleston's spell, though -- she writes of "that long history, the mildew and magnolias, the fierce old loyalties and that unarticulated sense of something stronger than the mere ephemera of modern lives spent on the move." She waxes eloquent, and often purple, on the Citadel's heyday in the 1950s and the careers of the men who earned their gold rings then. She assumes the portentous tones of a History Channel narrator to describe the clashing worlds of hidebound old boys and briskly arrogant New York lawyers, the paternalistic American past vs. the ERA. To her, the players in this drama are heroic archetypes shaped by fate and history and forever changed by their bruising battle. It can get a little tiring.

Perhaps because she covered the courtroom story in newspaper articles, Manegold is surprisingly sketchy on it here. We come to know Faulkner's opponents far better than we do her own legal team. The year she spent as a day student attending classes at the Citadel while the courts deliberated is barely mentioned. But Manegold was present on campus during Faulkner's awful days as a knob, and her intimate account is worth the price of the book. It reminds us that Faulkner wasn't the only recruit who headed home before a week was out; it shows us boys sobbing, sweating in fear, standing at attention until their muscles spasmed as they were screamed at by sophomore officers venting their rage over their own knob humiliations from the previous year. "It's boys taking boys and tearing them apart," one of Faulkner's classmates said. Faulkner winds up seeming admirable for walking away from a degrading and dangerous system.

Shannon Faulkner left the Citadel trailed by rebel yells of triumph from the barracks. On "This Week With David Brinkley," Cokie Roberts commented acidly, "I mean, if you are going to be a pioneer, you have to get on the covered wagon and go across the country and be a pioneer." Faulkner fell off the wagon, and many of us, at least privately, probably agreed with Roberts. Though "In Glory's Shadow" has its flaws, it adds important human dimensions to a case many of us may have judged too quickly.

Shares