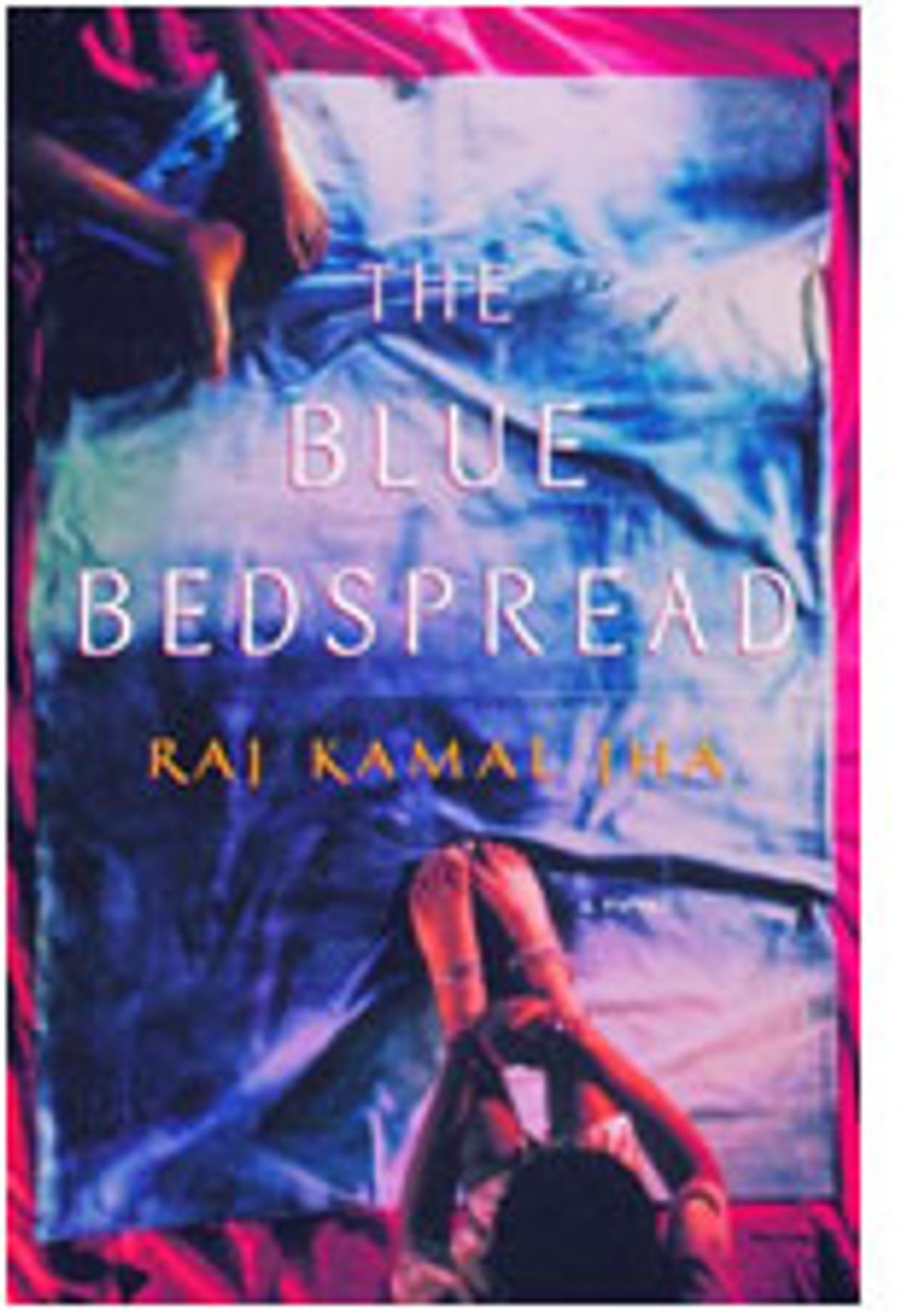

Not all that long ago, a novel like "The Blue Bedspread" would have been unthinkable in polite Indian society. Incest and sexual molestation, the subjects of Raj Kamal Jha's cinematic first novel, simply weren't discussed, let alone written about. But it is precisely Jha's bold interest in the unspeakable that distinguishes his book from what writer Amit Chaudhuri recently called the current "jamboree of Indian English writing."

Set in Calcutta -- a surreal, unrecognizable Calcutta where snowfall is commonplace -- "The Blue Bedspread" takes the form of a confessional. The nameless narrator learns that his sister, whom he hasn't seen in years, has died giving birth to a baby girl. Upon assuming custody of the infant, he spends one dreamlike night writing down the sordid history of his family. "I shall hold your hand," he promises the child, "open all those rooms that need to be opened, word by word, sentence by sentence. I will keep some rooms closed until we are more ready, open others just a chink so that you can take a peek. And at times, without opening a door at all, we shall imagine what lies inside."

The narrator's central project is evoking his childhood relationship with his sister, which is at once tender and repulsive. Fearful of the father who beats and molests them, the children seek refuge in each other's arms, under the protection of the bedspread on the bed they share. There, a "daily theater of pleasure and fear" is acted out, carrying the two "as if on a wave from one night to the next." This unspeakable secret, trapped within the narrator's chest, haunts him into adulthood. Dramatizing the narrator's sense of helplessness, Jha fills his story with images of entrapment: "dead insects trapped in the Plexiglas cover" of a streetlamp; pigeons flying around and around in a cage, their arc of flight constrained.

The themes of "The Blue Bedspread" are certainly daring, and many of Jha's images are striking. But the novel is written in an overly self-conscious style that, to me, takes away from the visceral impact it should have. Jha's long run-on sentences often seem strung together in a haphazard, pseudo-poetic way: "My tap in the bathroom drips, I have tried many things, I have turned the steel faucet all the way to the end, turned it again, hard, harder, so hard my fingers lock onto the steel, they still hurt."

And then there is Jha's fondness for color: not just the blue bedspread, but the blue towel, the blue dress, the red tiles, the red bicycle, the red handkerchief, the brown hills, the green lamps, the green window. Jha bludgeons us with, to use Gustave Flaubert's phrase, "a bewildering chaos of colors." I suspect that for the narrator to come to terms with the shadowy horrors of his black-and-white past, he must expose them to the vivid everyday present. But by piling up colors, page after page, Jha ends up deadening our sense of sight. We are far indeed from, say, a Krzysztof Kieslowski film, where colors signify in artful, nuanced ways. "The Blue Bedspread" may shock us, it may make us blush, but ultimately it fails to make us see.

Shares