Match the following quotes and occupations:

1) "I think that in part people are kept from becoming their dysfunctional selves by working for a corporation."

2) "I should go out and hike those hills and I should go for those walks while I'm still young -- while I can still do that kind of stuff -- instead of just sitting here wasting away."

3) "I'm, like, telling people to go fuck themselves on a daily basis. And that's because being in this job, you realize that money is the bottom line in almost everything."

4) "So rather than try to compare people and talk about who's got power and who doesn't, I think we should all sort of just put our arms around each other's shoulders and drink a beer and say it's a hell of a life, you know?"

A) Advertising executive, B) university systems administrator, C) Air Force general, D) Kinko's worker.

Correct answers? 1: D, 2: B, 3: A, 4: C.

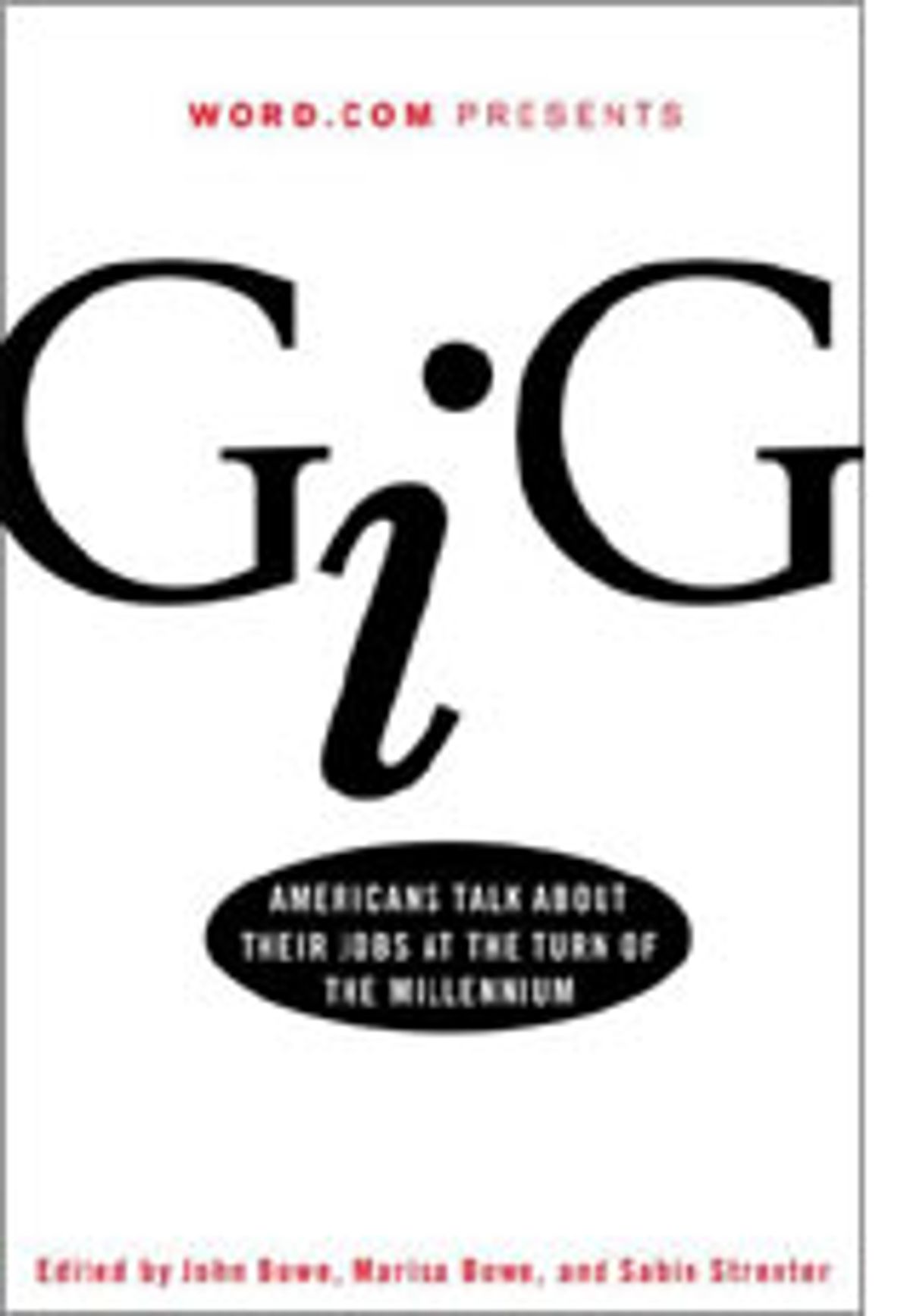

"Gig" is full of surprises like these -- stories of successful professionals filled with rage and regret and of workers in aggressive, demeaning or dangerous professions who are gentle, thoughtful or playful. The men and women interviewed in "Gig" range from preteen lemonade sellers to septuagenarians; they include a prostitute, a supermodel, an adhesives saleswoman, a taxidermist and a slaughterhouse human resources director. Perhaps because almost 40 interviewers participated, the individual voices remain distinct, with their personal, regional and class inflections intact.

"We were very moved by the wholehearted diligence that people bring to their work," co-editor and Word founder Marisa Bowe writes in the introduction. "Very few of those we talked to hate their jobs, and even among the ones who do, almost none said 'not working' was their ultimate goal."

"Gig" grew out of a weekly column in Word, called "Work," that was modeled on the interviews that formed Studs Terkel's 1974 "Working." Bowe tells us that some interview subjects were referred by readers of Word who thought they had friends or acquaintances with interesting jobs. I suspect that people who perform their jobs on autopilot don't often talk about them or don't make them sound interesting, so there is some sampling bias in the method. Still, the editors of "Gig" are on to something: The national mood does seem to be turning back toward a validation of work.

At the time Terkel's "Working" was published, trendy young intellectuals cast a cold eye on work. Gainful employment (except, say, at an anarchist vegetarian food collective or leftist bookstore) involved supporting the status quo, suppressing natural impulses in favor of delayed gratification, being competitive rather than loving, egoistic rather than communally minded. The hip and thoughtful tended toward socialism, believed in liberation through the ending of repression and indulged freely in sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll. Searching on "Working" on Amazon.com, I was taken back to those times. "Great book," one fellow wrote from Hawaii. "I read this book thirty years ago. It has probably kept me unemployed for most of that time. Warning: if you read this book you may quit your job."

Most readers of "Gig," however, aren't going to be dropping out of the "system" anytime soon. Today, trendy young intellectuals tend to want to buckle down and get to work. Part of this change in cultural mood stems from the liberalization of American society over the past 30 years. Kids who grew up smoking pot and having sex in high school may be less likely to treat their 20s as a prolonged bacchanal. Kids who grew up with parents who had nontraditional jobs may not blanch at the word "work."

On a less optimistic note, our newfound respect for work is also linked to the increased role of materialism and the decreased role of other values in our society over the past 30 years. With 50 percent of marriages ending in divorce, a retreat from the turmoil of private life into the relatively simple world of work is more appealing than it was in 1971 (as sociologist Arlie Hochschild argued in her last book, "The Time Bind"). We perceive fewer nonmonetary rewards in life, so the "cash nexus of capitalism" looks better and better.

Yet one of the inspiring aspects of "Gig" is how little most people talk about money as a component of their jobs. They leave jobs that don't pay enough and appreciate those that are rewarding, but overall, people seem more engaged by the tasks they undertake and the human contact they have -- even suspecting that they might be doing a little bit of good in the world. They are heartened by the feeling of competence they obtain from their work, even if, and sometimes because, it's not very challenging. If there's any advice for employers to be found here, it's to make sure the people who work for you feel that they are succeeding at their tasks.

And if there's any advice to be found in "Gig" for those choosing a career, it's to follow your intuition, not the conventional idea of what's prestigious or meaningful. The interviews suggest both the incredible breadth of experiences life offers and the surprising happiness most people find in the everyday. You can nearly hear them giggling nervously (the editors' most frequent note is "[laughs]") as they confess, almost guiltily, that they love what they do:

"I work six days a week, about twelve hours a day. And I'm doing great. I've never been happier in my life." (Michelle, "clutter consultant")

"They're in their job and where they really want to be is on the lawn and right now, I'm on the lawn." (Brian, lawn maintenance man)

"Even when I work seven days a week, which I do a lot, I don't mind. I'm just so happy." (Lisa, dog trainer)

"You probably haven't never seen anybody that loves their job more than I do mine." (James, produce-stand owner)

People in less prestigious occupations seem, if anything, happier and more convinced than other workers that their work is worthwhile. Perhaps it's because they have smaller egos to begin with, or because opting out of status competition makes for a more satisfying life, or -- scary thought for 2000's Ivy League grads -- because doing what you truly love doesn't typically mean becoming a lawyer, investment banker or physician.

Shares