It's an Ethics 101 classic: If you could have assassinated Hitler in 1938, would you have? Few would argue against a premature death for Hitler. But would eliminating him have prevented World War II and the slaughter of millions?

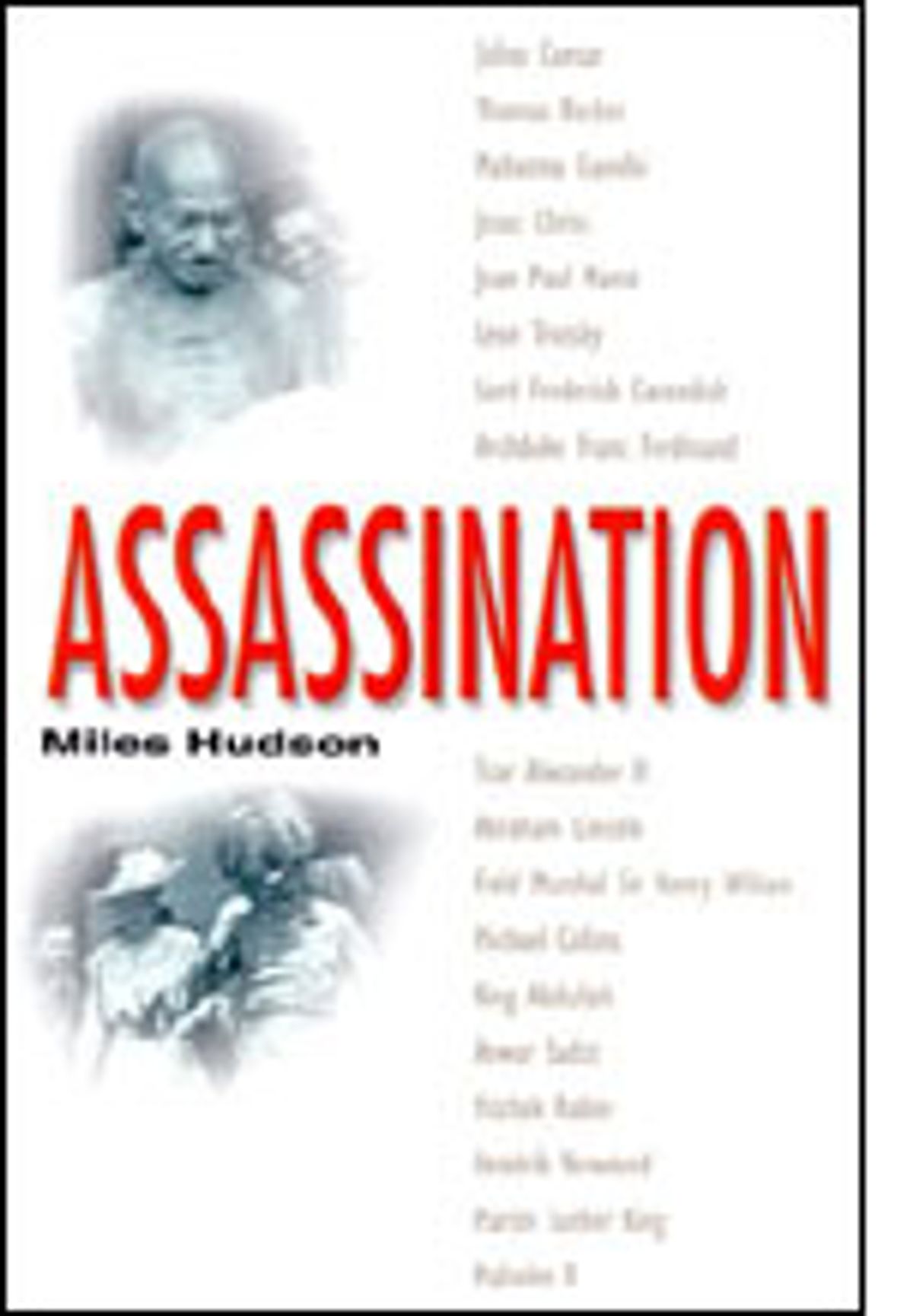

In "Assassination," Miles Hudson sets out to determine whether the violent removal of a critical historical figure at a crucial historical time makes any difference. To do so he has assembled 18 assassinations, ranging from that of Julius Caesar to that of Jesus Christ (though it's an asterisked one, a "judicial execution" rather than an assassination proper), and asked whether they worked.

Hudson, a conservative British political intellectual who now lives as a farmer, concludes -- unsurprisingly -- that assassinations almost never influence historical outcomes. "In over half the assassinations studied," he writes, "the result was the exact opposite of what was intended; in one-third of the cases nothing much happened; in one case, something else, a world war, was the result; and in only one instance can it be said that the assassin's sponsor succeeded in his political aims."

In the "exact opposite" category, Hudson places Caesar, Lincoln, Jean-Paul Marat and Martin Luther King Jr., among others. In the "nothing much" slot are Gandhi, Malcolm X, Anwar Sadat and Yitzhak Rabin. The assassination that produced the world war is of course Archduke Franz Ferdinand's in 1914. The lone successful assassination was that of Leon Trotsky, in Mexico in 1940. Hudson asserts it succeeded because all Stalin hoped to prove was that, if he wanted to, he could have Trotsky killed. In this sense, it was more a hit than an assassination.

So, if most assassinations are contextually interesting but historically meaningless -- if in nearly every instance Hudson discovered that assassination was not a useful instrument of policy -- why bother writing a whole book on the subject? I'm not entirely sure, but I'm glad that Hudson did, because "Assassination," which ranges from Imperial Rome to nearly the present day, is one of the best short histories currently available. Hudson covers the conflicts in the modern Middle East in 30 pages, the Civil War in fewer. He's able to pull it off because he deals in biographical sketches of assassinated figures rather than the grand sweep of events. But still, I now know more than enough about late-19th century Russia and the reign of Henry II (both of which were formerly vast holes in my knowledge) to fake it at cocktail parties for the rest of my life.

Throughout, Hudson deals with the assassination question in a balanced tone that might seem disaffected to some readers, too coolly judgmental to others. (He never lingers over what might be called the assassination "money shot": that moment when assassin and target finally meet.) This is primarily because he considers fanaticism, and the impulse to murder prominent leaders that seems to come with it, to be a fundamentally doomed proposition. Consequently, the reactionary anti-Union sentiment that persuaded John Wilkes Booth to shoot Lincoln and the fervent anti-Arab views of Orthodox Jews seem cut from the same cloth. Furthermore, Hudson suggests that most significant historical figures inspire envy and hatred in their own ranks at the same rate as admiration and loyalty. This is especially evident in the case of Malcolm X, who, Hudson argues, somewhat controversially but without a hint of equivocation was assassinated by his enemies in the Nation of Islam.

What Hudson seems to want to resist is anything that resembles the sort of historical romanticism -- almost always ineffective, at times ruinous -- that typically fires the confused soul of the assassin. No one is going to come away from this book with the sense that assassination is a good idea, and that's the way Hudson wants it. Maybe if the British or Germans had managed to eliminate Hitler, World War II would have ended early and millions would have been spared. But then again, maybe a sane leader would have assumed command -- and the war would have lasted twice as long. Assassination is the gasoline of history. Throw it on the fire and the fire blazes more brightly, more dangerously, for a brief period. But it's worth remembering: The fire was already burning.

Shares