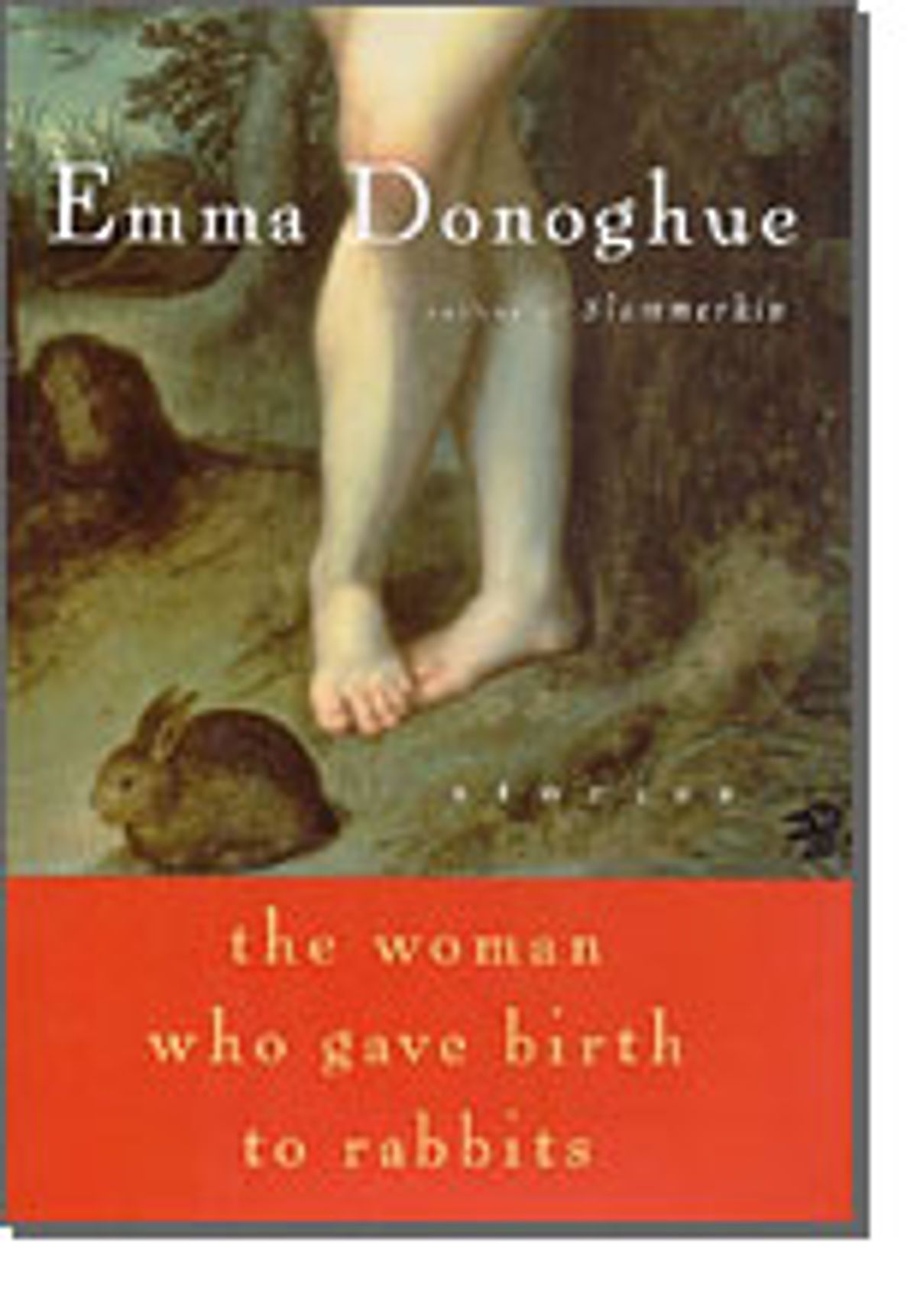

The only problem with Emma Donoghue's collection, "The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits," is that it's hard to stop yourself from skipping to the end of each story. There readers will find a note from Donoghue explaining the historical background of the juicy tale they've just read, whether it's the sailor who was drugged into marrying a spinster or the woman who, yes, faked the births of over a dozen dead rabbits.

Donoghue, the author of "Slammerkin," explains in her preface, "Over the last ten years, I have often stumbled over a scrap of history so fascinating that I had to stop whatever I was doing and write a story about it." Her endeavor results in the intimate kind of history we often crave, allowing us to be privy to the terrifying, scandalous or heartbreaking conversations that history books usually leave to our imaginations.

And leaving such historical details to Donoghue's imagination might be the next best thing to knowing what really happened. Donoghue animates these obscure pieces of the past with often humorous dialogue and surprising emotional invention. Some notable figures make appearances, such as feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft and Victorian art critic John Ruskin. Still, we don't see them in the phases of their lives that we'd suspect anyone -- except, it seems, Donoghue -- would choose to flesh out.

In "Words for Things," Donoghue imagines Wollstonecraft's little-known career as a governess. It's a mystery why she was dismissed from her job, and Donoghue examines the sudden departure from the point of view of her young charge, Margaret King: "Her mind was busy wondering what she had done wrong, what brief immodesty or careless phrase would make her governess punish her so, by leaving without a word." Donoghue isn't trying to answer questions or solve mysteries, but rather to touch on the aftermath of a true event and the ripples of change that powerful figures leave behind.

In "Come, Gentle Night," the newly married John Ruskin and his young bride, Eupehmia Chalmers Gray, envision their days together and all of the small pleasures they will enjoy. Yet when they attempt to consummate the marriage, Ruskin stops. Seeing her naked, he remarks, "So different from the statues."

When Euphemia is obviously disturbed, Ruskin exploits what he believes is his wife's ignorance of sexual matters and blames his own sexual failings on his wife's fragile state: "You are so very young -- not yet twenty -- and your system has been subjected to such anxiety." Donoghue doesn't fail to note in the postscript that Euphemia leaves Ruskin on the grounds of nonconsummation, remarries and eventually bears eight children. So much for a weak constitution.

In many of Donoghue's stories, she dramatizes women's small acts of heroism, or the injustices they suffered. The most affecting is "Cured," which excruciatingly draws out a 19th century London clitoridectomy, one of the surgeon Isaac Baker Brown's many attempts to rid women of hysteria and supposed promiscuity.

"Cured" has all the elements of horror -- the seemingly benevolent, handsome doctor; a trusting but desperate woman (a housekeeper who's really just suffering from back pain); gently persuasive promises of a cure and a sudden operation. "I swear to you, Miss F.," Brown assures his patient. "I have seen women who were morally degraded, monsters of sensuality -- until my operation transformed them." In her typically chilling way, Donoghue imbues a trivial historical figure with a voice that renders him unforgettable and, ultimately, monstrously important.

Shares