The dirty secret about combat memoirs isn't that war is senseless or that heroes are often terrified or that the battlefield can turn even good men into dehumanized monsters or that everyone is bored except for the moments when they're scared shitless or even that there is a beast inside every last one of us. The secret is that these stories are all more or less the same, once you decide which of two categories they belong to: tales of valor and tales of squalor.

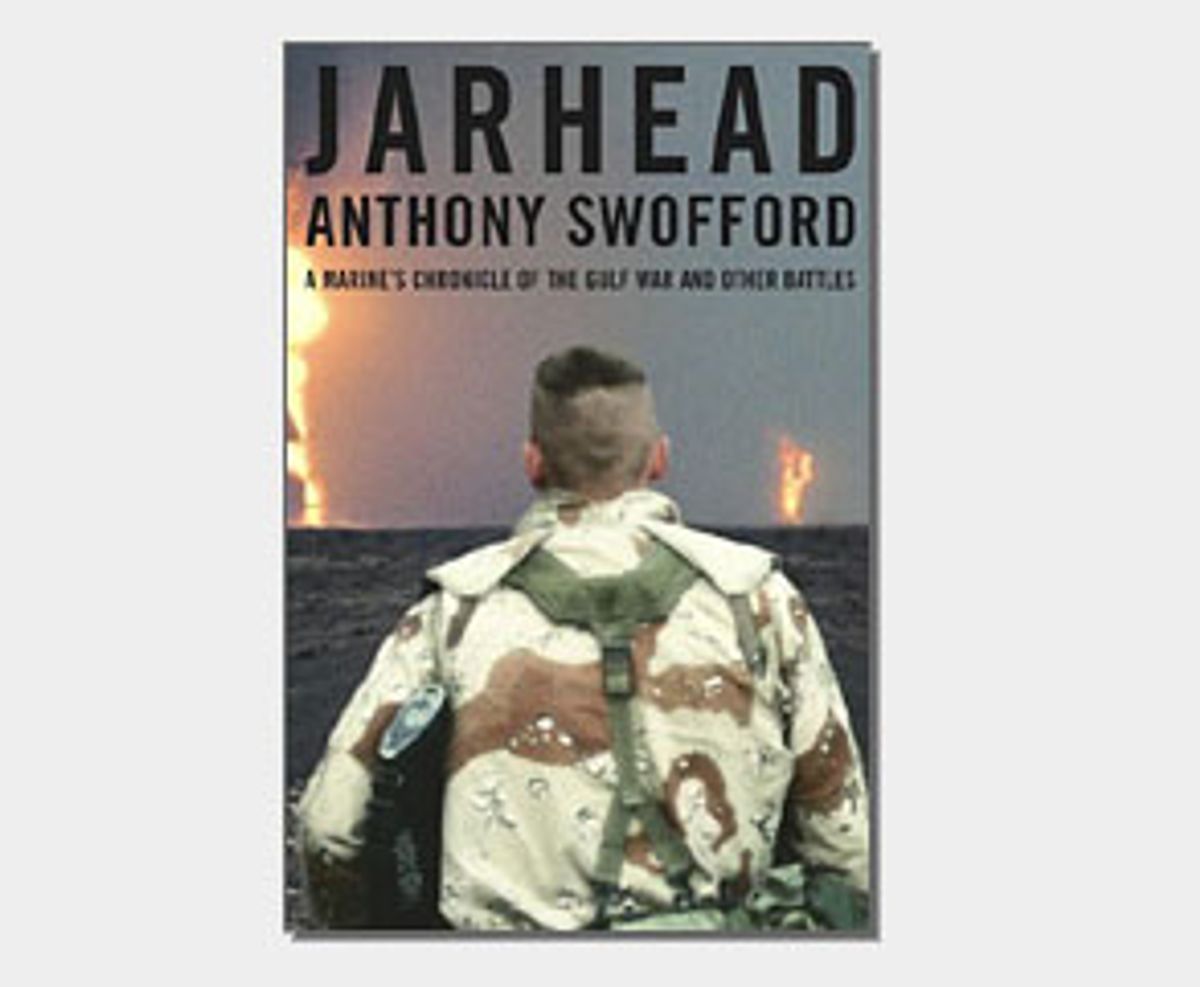

The tales of valor have enjoyed a resurgence of late, particularly those about World War II, but despite "Band of Brothers" and other enterprises of the late Stephen Ambrose, the second, bleaker type of war story is still ascendant. Its touchstones are Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" (a novel, but still) and Tim O'Brien's "The Things They Carried," books that strive to explain that, stupid as it is to fight wars, it is even stupider to glorify the fighting of them. And, more recently, war memoirs verge on disparaging themselves, so dark and roiling is the contempt to be found in them. Anthony Swofford's "Jarhead" is one of those books; you imagine him half-wishing, as he gets to the end of the book, that he could reach back and start erasing it from the beginning.

Swofford was a lance corporal in a United States Marine Corps scout/sniper platoon who saw combat in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait during the Gulf War. Specifically, he was fired upon by both the enemy and his own side, but didn't actually kill anyone himself. His war was short, and it only takes up the last third or so of this slender book. Of necessity, Swofford devotes more pages to his childhood and youth, his training in the U.S. and overseas, and the several months he spent stationed with his platoon in the Arabian desert waiting for the war to begin.

Initially, "Jarhead" delivers some jolts. Marine barracks are not known for their decorum, but Swofford describes his mates and himself as brutal, petulant, thoughtless, wretched, sadistic, wrathful and sometimes borderline sociopathic. He remembers being beaten mercilessly by a sergeant, holding a gun to the head of a fellow Marine until the other man wept uncontrollably, fantasizing for hours about the "pink mist" resulting from a properly-aimed shot to an enemy's head, contemplating suicide, auctioning off seminude photos of his unfaithful girlfriend, looting the corpses of Iraqi soldiers for trophies and consuming impressive amounts of cheap booze and porn.

From "Jarhead," you will learn that Marines pump themselves up by watching war movies on video: "We yell Semper fi and we head-butt and beat the crap out of each other and we get off on the various visions of carnage and violence and deceit, the raping and killing and pillaging. We concentrate on the Vietnam films because it's the most recent war." The fact that these films are meant to be antiwar doesn't faze them. "Actually, Vietnam war films are all pro-war," Swofford writes, "no matter what the supposed message." Marines love them because "the magic brutality of the films celebrates the terrible and despicable beauty of [our] fighting skills."

You will also learn that both of the Marine recruiters Swofford met with in his 17th year (the first time around he couldn't get permission to enlist from his father, an Air Force veteran who said, "I know some things about the military that they don't show you in the brochures") made access to inexpensive foreign prostitutes a highlight of their pitch. And that despite their hearty enthusiasm for the services of such ladies (not really available in Saudi Arabia, it must be said), the Marines Swofford served with were obsessed with the fidelity of the wives and girlfriends they'd left in the States. They maintained a "Wall of Shame," a post to which they duct-taped photographs of cheatin' women with notes detailing their betrayals: "This bitch fucked my brother," etc.

And then there's the grotesquely sexualized horseplay and hazing, the preoccupation with homosexual acts and the inability to distinguish them from violent domination: the "boot" Marine who was nicknamed "Ellie Bows" and referred to by the feminine pronoun; the football game that degenerates into a "field-fuck" of pantomimed sodomy inflicted on "typically someone who has recently been a jerk or abused rank or acted antisocial"; tricking the new guy into thinking they're going to brand him with a red-hot coat hanger; referring to mouths -- and new recruits -- as "cum receptacles."

Finally, you will see that if the creative impulse flourishes anywhere in the Marine Corps it is in the elaboration of spectacular profanity. One recruit parodies drill instructors by strutting through the barracks, hollering "You cumsuckers don't love my Corps. You shitbags disparage the memory of Chesty Puller every day with your lazy carcasses lying around on these cots like desert princesses jerking your rotten clits!" A sergeant knocks the Fifth Regiment as "all the inbreeds and degenerates. They came from the same mama somewhere in the woods of North Carolina. A big old green, wart-covered jarhead-mama. She shits MREs and pisses diesel fuel." (MREs, meals ready to eat, are the dehydrated food on which soldiers survive in the field.) A drill instructor orders Swofford, chosen to be the camp's Catholic lay reader, to "pray like a motherfucker."

Rough stuff, but not exactly unexpected in a group of young men who are first holed up together in close quarters and then thrust into extreme and immediate danger. Although Swofford is a fine writer, there's nothing especially revelatory in his account of the misery of a grunt's life: vomiting as he burns the contents of the "shitter," a punishment detail; the perpetually broken or missing equipment that doesn't do what it's supposed to do even when intact; the long, hot marches that render his crotch "sweaty and rancid and bleeding."

While it's true that we're preparing to send more Marines like Swofford back into the same country to fight the same foe that he writes about here, what they'll experience psychologically won't differ significantly from what fighting men everywhere have always endured. Whether you're freaking out because the wide-open desert makes you feel exposed or because the jungle can hide hundreds of lethal enemy soldiers, the freak-out itself is pretty much the same. When Swofford dwells on the treachery of the environment in "Saudi," what he says about sand could just as easily be said about jungle: "this most unstable material or medium that will make futile all effort or endeavor."

It's not its timeliness that makes "Jarhead" an object of fascination, but its exoticism. Americans haven't fought a major war in generations. For our average male citizen, military service -- a universal experience for most men throughout human history -- is an alien notion. Yet we haven't shaken our age-old sense that war is a crucible of masculinity, and now those who strenuously resisted the draft when they were eligible can afford to be swayed by the romance of war. Swofford had the misfortune of succumbing to that romance, and to his own "intense need for acceptance into the family clan of manhood," when he was still young enough to sign up.

He began regretting that decision almost as soon as he'd acted on it, and "Jarhead" thrums with a ceaseless litany of curses and self-flagellation. The lot of the jarhead, Swofford explains again and again, is wretched, and the jarheads themselves base. They travel miles to escape their own kind. Their wives and girlfriends don't cheat because they're bored, but because "everyone loves to get over on the jarhead."

"Like most good and great marines," he writes, "I hated the Corps. I hated being a marine because more than all of the things in the world I wanted to be -- smart, famous, oversexed, drunk, fucked, high, alone, famous, smart, known, understood, loved, forgiven, oversexed, drunk, high, smart, sexy -- more than all of those things, I was a marine. A jarhead. A grunt."

But Swofford is smart, and, like most of his fellow Marines, he knows he suffers and may die to secure America's access to oil fields he'll never profit from. "None of the rewards of victory will come my way, because there are no rewards, not on the field of battle, not for the man who fights the battle -- the rewards accrue in places like Washington, D.C., and Riyadh and Houston and Manhattan, south of 125th Street." This is how it works now; a nation's rulers no longer lead their people into battle as Charlemagne once did. Even the middle class mostly manages to keep itself out of the fray. The soldiers come from a social strata that's not "us," which makes it that much easier for those who watch from the sidelines to wax hawkish -- and turns the lives of fighting men into an object of marveling curiosity.

Not surprisingly, his tour of duty makes Swofford feel like a chump, and in the portions of "Jarhead" that describe his life after he gets out of the Marines, he wants nothing more than to shake off his former identity. Hatred of the Corps feeds into self-hatred for being the type of guy who enlisted, like a snake eating its own tail. The feeling that he and his comrades "would always be jarheads" plagues him. There are varieties of pain in "Jarhead," submerged beneath the terrors of battle and the pangs of a rotten crotch, so exquisite they'd do a torturer proud.

The biographical information on the book's jacket flap explains that Swofford attended the Iowa Writers' Workshop, and it's easy to imagine him there, this guy who read "The Iliad" during breaks in weapons training. I can picture him striving to make a new, better life that transcends the "loneliness and poverty of spirit" of his jarhead adventures, while surrounded by fresh-faced, unscarred young aspirants who envy him his fabulous, fabulous material.

Shares