genius n. -- One who possesses a strongly marked quality or aptitude; to be endowed with transcendent mental superiority.

hack n. -- One who begins magazine articles with a dictionary definition.

OK, Andy Kaufman was a genius. No argument here. Still, I found myself cringing not long into "Man on the Moon" -- and not just at the sight of a gray, puffy Lorne Michaels playing his 30-year-old self. "How about 'The Chris Elliott Story'?" I snarled to a friend. "If only he'd get cancer."

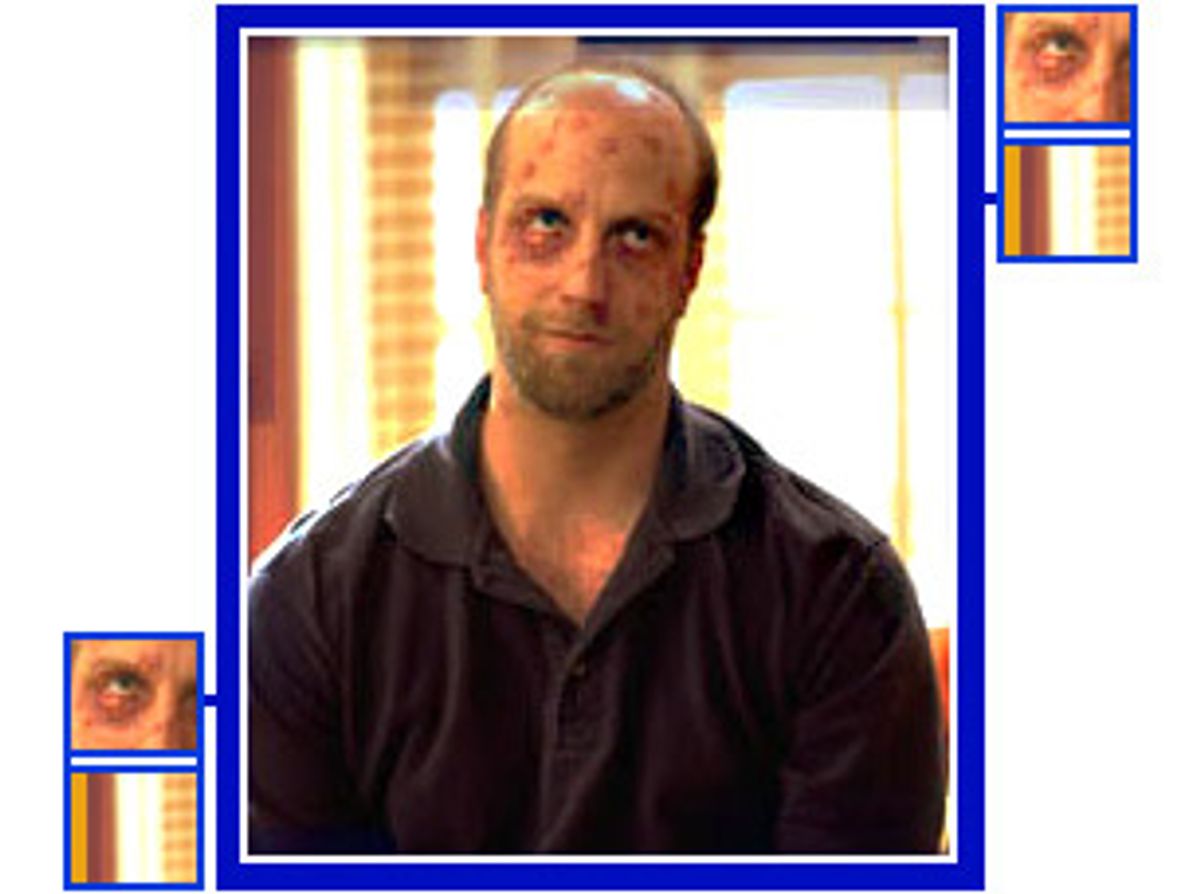

While Kaufman has been resurrected in film, books and 12,000 magazines as a mad comedic savant, Elliott -- he of "Late Night with David Letterman" and "Get a Life" fame -- is, well, the voice of Dogbert, an ignominious fate for a performer who is every bit as innovative, bold and bafflingly odd. And funnier. (Let's face it: The reason "Moon" was made, apart from some altruistic effort to get Jeff Conaway off food stamps, is because cancer kills at the box office.) Like his comedic forefather, Elliott eschewed jokes in favor of joking around. He walked (nay, banana-danced upon) the line between comedy and performance art. And long before they recorded "Man on the Moon," R.E.M.'s "Stand" stood as the theme to "Get a Life." Elliott must be a genius; Michael Stipe says so.

Although Kaufmania has enveloped the media, the masses haven't bought in; "Moon" brought home about $34 million at the box office through the end of January, less than Carrey's infamous flop "The Cable Guy." (I guess we won't be seeing "The Judd Hirsch Story" anytime soon.) Meanwhile, Elliott is making his own low-key comeback. Last year Rhino released several "Get a Life" episodes on video (with DVD release scheduled for March). The Net is littered with bootleg cassettes featuring his best "Late Night" appearances and the sublime cable special, "Action Family," which simultaneously mocked sitcoms and action shows (imagine "Father Knows Best" with Robert Young as a tough-guy cop). TV Guide declared one "Get a Life" episode -- in which Chris stars in the community-theater musical "Zoo Animals on Wheels" -- the 19th funniest moment in TV history. And now he returns to the big screen as the villain in "Snow Day," costarring alongside, ahem, Chevy Chase. (Hey, it's a start.)

"I like moments that are uncomfortable but funny at the same time," Elliott once said. "Kaufman used to do that to perfection." Indeed, Elliott harvested mass quantities of discomfort as the bearded, brilliant jerk on "Late Night," where he honed his wise guy-doofus persona -- smarmy-pants to Letterman's smarty-pants. His appearances thrummed with the confidence of an idiot. As the Panicky Guy, the Guy Under the Seats, the Fugitive Guy or his own unctuous self, his comedic machismo overpowered even Letterman, whose one-liners bounced off Elliott's steel-plated sarcasm. ("Maybe we should check the joke-meter on that one. I think you broke a world's record.") Kaufman fearlessly read "The Great Gatsby" to a yawning audience; Elliott balanced his scribble-ridden checkbook on national TV ("Dave, does this look like 'inflatable rubber raft' to you?")

Like Kaufman, Elliott could morph into the creepiest alter egos. His Marlon Brando may be the most unsettling celebrity impersonation ever (with the possible exception of Tom Green). Less an imitation than an excuse to jerk around on national TV, Elliott's Brando did a dadaist banana dance and spouted Tony Cliftonian verbal assaults. He wasn't mocking Marlon but co-opting him as a spleen-venting vessel. ("The green room, ladies and gentleman, isn't exactly green. In fact, it's painted white -- as white as my big ass!") Even Dave's hipper-than-thou audience often watched in stunned silence.

While "Late Night" dismantled television, Elliott dismantled the show that dismantled TV. He once ridiculed clip-happy guests by plugging his own film -- not a movie but a fuzzy black-and-white video from a stay in a sleep-disorder clinic, which climaxed with a psychopathic nurse smothering him into unconsciousness. ("I'm very proud of it," he kvelled.) Funny was secondary; he went for the kill, even when the prey was the hand that fed him. As the host of "Night Light," a five-minute, desk-and-two-chair comedy show that broadcast some 20 feet from Dave, Chris tweaked Letterman as fidgety, complaining and bitchy. It was a TV first: a talk show mocking the talk show that mocked talk shows. Watching a homemade collection of his best "Late Night" bits, I was shocked to see how much time Letterman gave to Elliott -- and what a sharp comedy duo they made:

Chris: "I came out here tonight to tell you something special. My wife and I just got back from vacation, and I lost my virginity."

Dave: "And I lost a bet."

Chris: "I don't know what that means. Anyway, we have the pictures."

Dave: "Of your vacation?"

Chris: "No. Of us doing it. All in all, my wife was very kind and patient with me. Here we are in the thick of it. And here I am crying."

Dave: "Looks like something you'd see at Rikers Island."

Elliott graduated to "Get a Life," his cult masterpiece, playing Chris Peterson, the pathetic, bathetic 30-year-old paperboy still living with his parents. Kaufman left a negligible influence; the work is his legacy. But "Get a Life," wrote Tom Shales in the Washington Post, "ushered in the '90s on a note of addle-pated insanity ... how appropriate that would turn out to be." Before "The Simpsons" found its hip groove, Elliott was aping sitcom conventions, like the clip-show clichi, which Matt Groening went on to copy. Before "You killed Kenny" became a "South Park" tag line, Chris' character died in about every other episode (strangulation, gunshot wounds and tonsillitis were among the causes). And before "Seinfeld" blossomed into a show about a misanthropic, immature loser, Elliott had been there and done that.

Which isn't to say he was above good old-fashioned parody. In an "E.T." spoof, Chris adopts a vile, blobby alien named Spewey. ("It's an acronym," he explains. "It stands for Special Person Entering the World -- Egg Yolks.") Elliott befriends the creature despite Spewey's penchant for random assault and yogurty excretions, which to Chris taste like "nectar of the Gods." What to do with Spewey? As we learn in the (a)typical sitcom resolution, the blob turns out to be delicious "and self-saucing."

Then there's "Zoo Animals on Wheels," in which he plays a roller-skating wildebeest in a "Simpsons"-worthy musical:

"I'm the lonely wildebeest ... Proud yet frail from my nose to my tail. But here's the good news, I've got wheels -- on my shoes!"

But satire, another Kaufman once said, is what closes on Saturday night. Such was the fate of "Get a Life," which died after 34 episodes. Elliott has been wandering the show-business wasteland ever since -- his catch-phraseless comedy seemed out of place in a brief stint on "Saturday Night Live," and "Cabin Boy" justifiably tanked with critics and ticket-buyers alike. (Though I'll watch it before "The Waterboy" any old time.)

Yet without Elliott there might have been no "Beavis and Butt-Head," no Farrelly brothers and, in the What-hell-hath-Chris-wrought? department, no Adam Sandler, Rob Schneider or David Spade. If Kaufman had lived, he would likely have slipped into a similar show-biz abyss; after all, there are only so many sketch shows to sabotage, so many ways to cry wolf. But along came cancer and Carrey and Forman and legendary status.

If only Chris Elliott had been so lucky.

Shares