The U.S. government, its military, its press and its people have operated in ignorance of Iraq from the beginning. The United States invaded Iraq blindly, occupied it blindly and is now blindly trying to find a way to escape. In this darkness, the publication of Anthony Shadid's "Night Draws Near: Iraq's People in the Shadow of America's War" is an important event, a ray of light. This is the first book about the Iraq war to tell the Iraqi side of the story. It is painful and necessary reading.

Shadid, a reporter for the Washington Post, takes readers into the homes, and minds, of Iraqis of every stripe -- from a Baghdad doctor who loves America but has no idea why America wants to invade his "pathetic" country to an impoverished single mother trying to feed her eight children; from a government minder who ends up becoming Shadid's best Iraqi fixer -- and friend -- to a devoutly religious young peasant who resolves to die fighting the occupiers. Informed, scrupulously observed, elegantly written and deeply compassionate, "Night Draws Near" is a classic not just of war reporting but of what we might call frontline anthropology. Although it takes no sides and expresses no partisan opinions, Shadid's book may be the most damning indictment yet of the Iraq war.

An Arab-American of Lebanese descent who speaks fluent Arabic and has reported from the Middle East for 10 years, Shadid was able to penetrate deeper into Iraqi society during the war period than any other reporter I know of. Most Western reporters in Iraq speak little or no Arabic and have to learn Arab and Iraqi culture from scratch. Furthermore, few of them have developed long and intimate relations with ordinary Iraqis, which can result in clichés, wooden statements devoid of nuance, or interviews in which the suspicion arises that the source is simply telling the reporter what he thinks he wants to hear. Because Shadid was able to develop long-term relationships and friendships with many sources, he was able not only to penetrate beneath the surface but to capture how Iraqis' feelings about the Americans evolved over time. (They did not grow fonder of us.)

But perhaps even more important than his skilled and intrepid reporting, for which he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 2004, is Shadid's combination of open-mindedness and sophistication, his willingness to simply listen to what Iraqis say and report it with rare understanding. Perhaps because of his ethnic background, Shadid does not exoticize his subjects. From a perspective that combines journalism and anthropology, he has a deep enough knowledge of Iraqis' culture, political beliefs and religion to understand them and convey their shared humanity, but he is not so far inside their worldview that he loses all critical perspective. Seen through his eyes, a devout young man in Fallujah preparing to fight the Americans is neither a cartoon "Islamofascist" -- the right-wing version -- nor a cartoon revolutionary fighting the righteous fight against American imperialism, the far-left version. Rather he is something much easier and harder to understand: a Sunni Arab at a certain place and time, the product of history yet a free individual, at once familiar and strange.

If the architects of this disastrous war had tried to grasp these complexities, and how they might play out in Iraqis' reaction to the invasion, we might not find ourselves in our current plight. (To be sure, those on the radical left should have listened, too. The consequences of their failure to do so, however, were somewhat less significant. The failures of the right led to a calamitous war; the failures of the left led to bombast from the likes of International ANSWER.)

Most of the events in "Night Draws Near" take place between March 2003, when Shadid arrived in Iraq weeks before the invasion, and June 2004, when he left. In the book's prologue, however, he recounts an event he witnessed in 2002, when Saddam Hussein, facing invasion and attempting to rally popular support, suddenly released all of Iraq's untold thousands of prisoners. Shadid was present at Saddam's largest and most notorious prison, Abu Ghraib, when the prisoners emerged, in a wild eruption of joy, furtive rage at Saddam, increasingly bold calls for justice and emotional hysteria. "In the cathartic scenes that followed -- moments unparalleled in Iraq's history, perhaps in any history -- the hidden complexity of a country we knew only by its surface played out before us," Shadid writes. "The powerful forces we saw fermenting beneath the veneer of absolutism would reappear, five months later, during the aftermath of the American invasion and Saddam's fall." Those fermenting forces included some that Americans expected -- joy at liberation, anger at Saddam -- but others were more unpredictable.

Shadid speaks of the "combustible ambiguities of Iraq -- the ancient pride, the desire for justice, the resilience" that "were emerging from beneath the fear, conformity and silence" of Saddam's long rule. He never articulates exactly what it was he witnessed that day at Abu Ghraib that ran counter to America's received images of who Iraqis were and how they were going to behave. Certainly the behavior he describes on that day, however chaotic, was not as disconcerting to American assumptions as the later massive Iraqi rejection of the occupation and the nearly universal lack of gratitude for being freed from Saddam. His point is larger, more rooted in the dark byways of history: Iraq was a strange and culturally alien country and people, with an inconceivably long history and a long list of grievances against the United States and the West. It was arrogant folly for Americans to think they could predict the outcome of invading such a place, of trying to change the course of history. "When the Americans arrived, its soldiers, diplomats and aid workers marched into an antique land built on layer upon layer of history, a terrain littered with wars, marked by scars, seething with grievances and ambitions," Shadid writes. "Willingly or not, they added their own chapter to this chronicle. The Americans came as liberators and became occupiers; but, most important, they served as a catalyst for consequences they never foresaw."

Americans failed to anticipate the bitter consequences of their intervention -- the rise of Islamism, the bloody sectarian struggles, the rejection of the occupation -- because of the seemingly unbridgeable gulf between America and the Arab world, "two cultures so estranged that they cannot occupy the same place." The painful, even tragic irony is that it was precisely the most altruistic of America's numerous and shifting motivations for the invasion that proved the superpower's fatal blind spot. Americans, Shadid argues, were misled by their fixation on Saddam's dreadful regime. "Our nearly absolute emphasis on the all-encompassing tyranny blinded many of us to everything else that was there," he writes. "Time and again, we envisioned, or were given, a simple, two-dimensional portrait of a country, waiting for aid and dreaming of freedom as it suffered under the unrelenting terror of a dictator ... Once the dictator was removed, by force if need be, Iraq would be free, a tabula rasa in which to build a new and different state."

This was, and is, the moral justification used by the Bush administration, and righteously proclaimed by the pro-war liberals who made the fateful choice to sign up with the most reactionary, and incompetent, administration in modern American history. Of course, as Shadid points out, there were larger strategic reasons for the invasion. "If we can change Iraq, George W. Bush and his determined lieutenants maintained, we can change the Arab world, so precariously adrift after decades of broken promises of progress and prosperity. This rhetoric -- idealistic to Western ears, reminiscent of century-old colonialism to a Third World audience -- envisioned the dawn of a democratic and just Middle East, guided by a benevolent United States. For the Americans, aroused by fears of terrorism, Baghdad, the capital of the Arab world's potentially most important state, was the obvious choice for a place to begin a wave of democratic reform. This rationale for invasion ran at least as deep as the illusory warnings about weapons of mass destruction or the rhetoric emphasizing the tyranny of Saddam. Iraq was an instrument of change for the U.S., a lever to pull, the first Middle Eastern domino to fall."

Those grandiose dreams, like pieces on a Risk board set up by a child in the middle of a busy street, lie scattered today, as Islamist terrorists run amok, the mullahs in Iran sit in the strategic driver's seat, America and its ally Israel are even more despised throughout the region than before and Iraq hangs on the edge of a civil war, its people traumatized by two and a half years of violence and chaos. By deposing Saddam and removing all authority, the United States opened the Pandora's box of Islamism. As in a nightmare, by trying to prevent something from happening, America did exactly the reverse. Shadid's book is a gripping, on-the-ground report about how things went so terribly wrong. The story Shadid tells does not entirely fit into the ideological assumptions of either conservatives or liberals -- neither of which was particularly coherent. But it vindicates the liberal position far more than the conservative.

Shadid's tale begins with the American invasion, which he witnessed firsthand from Baghdad. Before he arrived, he had been reporting from other countries in the Middle East, where anti-American sentiment, largely muted in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, was raging in response to subsequent U.S. policies. "The American response to the destruction of that day -- the martial rhetoric of the Bush administration; the dispatch of the U.S. military to Afghanistan; and the detention of prisoners at the military base in Guantanamo Bay -- had evoked Arab anger as the lopsided conflict between Israel and the Palestinians accelerated further. Anyone who defied the Americans was admired. Osama bin Laden, whose venomous ideology actually alienates the vast majority of Arabs, had become an unlikely folk hero." When Shadid arrived in Iraq, this strident anti-Americanism (expressed in a hit pop song blasting the coming invasion and invoking "Chechnya! Afghanistan! Palestine! Southern Lebanon! The Golan Heights! And now Iraq, too?" with the refrain "Enough! Enough! Enough!") was replaced by a nervous quiet. But later, after the invasion was over, Iraqis began to voice the same bitter grievances. It turned out Iraq, even after being liberated, was still an Arab country, and a Muslim one.

Again and again, when talking to Iraqis, Shadid found deep historical grievances against the U.S and the West. Far more than Americans ever understood, Iraqis remember and are bitterly resentful of British colonialism -- a view that colored their attitudes toward the American invaders from the start. It is not as if this was unknown: It is a central theme of Rashid Khalidi's prescient "Resurrecting Empire," written before, during and immediately after the invasion. But the neocons who plotted the war were ignorant of history and convinced that the Americans' noble intentions would set them apart. In this belief, they unwittingly followed in the footsteps of the British. Shadid writes, "There's a line from history that nearly everyone in Baghdad remembers: 'Our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.' The speaker was Major General Sir Stanley Maude, the British commander who in 1917 entered the capital to end Ottoman rule ... The idea has proved memorable. So has the aftermath, a legacy that Iraqis ruefully note. The British remained in Iraq and in control of its oil for decades." The fact that the Bush administration uttered almost exactly the same line about its intentions was, of course, also noted in Baghdad.

To the skepticism born of colonial rule was added profound distrust of America. There are several reasons for this -- its role in the first Gulf War, its support for the devastating U.N. sanctions (Shadid notes that the sanctions doubled Iraq's infant mortality and led one-third of 6-year-olds to drop out of school), its betrayal of both the Kurds and the Shiites during the first war -- but probably the biggest one is America's nearly total support for Israel. The plight of the Palestinians is the open wound of the Middle East, the grievance felt most deeply and bitterly by Arabs and Muslims around the world. And again to a far greater degree than Americans who have not traveled in the Arab world realize, the issue of Palestine has poisoned the goodwill Arabs once felt for America. Iraq is no exception. Shadid notes that even the official American announcement, in May 2003, that it was an occupying power deepened the rift between the U.S. and Iraqis because for Arabs, the word "occupation," ihtilal, conjures up searing images of Israeli tanks smashing through refugee camps. Iraqi anger over the Israeli treatment of the Palestinians, and over America's unqualified support for Israel, boils up many times in this book.

The views of Dr. Adel Ghaffour are typical. As the war loomed, Shadid paid a visit to Ghaffour's clinic, which he ran for mostly poor patients during off hours from his faculty job at the University of Baghdad. Ghaffour was born in Iraq but lived in America for 10 years and was married to an American woman. Like many Iraqis, Ghaffour recalled the 1970s as a golden age. "You could see that in a few years we were ready to leave the developing world," he told Shadid. "It really is a human tragedy. I doubt in history a nation has suffered like Iraq. For no good reason."

Adel was no enemy of the U.S. "'I love that country,'" Adel told me. 'If there is a paradise, it is there' ... Like others in Baghdad, he insisted that of the Arabs, the Iraqis were the most similar to the Americans -- in the way they worked, the way they lived, the way they enjoyed themselves ... His affection didn't extend to U.S. foreign policy, though. Adel, like nearly all Arabs, blamed the United States for its unswerving support for Israel, a stance that defied logic to most in the region. The support was so unrelenting, so unqualified that Adel, like many here, relied upon complicated conspiracies to explain it."

With bitter memories of a supposedly "liberating" colonial occupation and a deep distrust of America's intentions, Iraqis did not have a reservoir of goodwill to grant its new occupiers. And as Shadid learned, certain national traits did not predispose them to welcome the Americans with open arms, either.

A conversation Shadid had during the first week of the war with an educated Iraqi family revealed some of these characteristics, and presaged many of the problems to come. Shadid's friend Omar invited him to have lunch with Omar's family in their middle-class home in Baghdad. The party was made up of Omar's father, Faruq Ahmed Saadedin, an urbane former diplomat; his wife, Mona; their adult daughter, Yasmeen; and Omar's wife, Nadeen. The family was Sunni, but did not dwell on sectarian differences and regarded it as rude to bring them up -- a civilized attitude that Shadid writes was common among Baghdadis.

Despite their severely strained nerves -- the family had been kept up night after night by U.S. airstrikes, and an air raid siren sounded during Shadid's visit -- Omar's family put on a lavish traditional Iraqi lunch, over which the conversation turned to politics. Faruq, who had quit the Baath Party in 1968 (a decision he blamed for his failure to become an ambassador), dared to openly criticize Saddam as rash. "Iraq is ready for change," he said. "The people want it, they want more freedom."

For Shadid, this unusually open conversation with Omar and his family provided a crucial insight into Iraqi attitudes. "Omar and Faruq came to embody broader assumptions at work in their embattled country. Each represented currents, their depth yet unknown, that would greet U.S. soldiers on their imminent entry into Baghdad."

For Omar, "American promises of liberation were no more than rhetorical flourishes to a policy bent on domination, furthering U.S. and Israeli interests in the Middle East." His father was less bitter, more nuanced in his thinking: "He was no less skeptical, no less suspicious, but he saw the shades of the moment before him. Iraq was changing, and Faruq was already struggling to see the direction it would take.

"But the men converged in their denunciations of the very rationale of the American invasion," Shadid writes. "Their words reminded me of something I had long felt in Iraq. Perhaps more than any other Arab country, it seemed to dwell on traditions of pride, honor, and dignity. To Faruq and Omar, the assault was an insult. It was not Saddam under attack, but Iraq, and they insisted that pride and patriotism prevented them from putting their destiny in the hands of another country. 'We complain about things, but complaining doesn't mean cooperating with foreign governments,' Faruq said as if stating a self-evident truth. 'When somebody comes to attack Iraq, we stand up for Iraq. That doesn't mean we love Saddam Hussein, but there are priorities.'"

Not all Iraqis shared these sentiments. Fuad Musa Mohammad, a psychiatrist and a Shiite, "was the kind of Iraqi the United States had hoped to encounter once in Baghdad": He despised Saddam, loved America and welcomed the invasion. But even Fuad warned Shadid that the U.S. would have only a "perilously brief" opportunity to prove to skeptical Iraqis that its intentions were good. "'I like America, really. I like the American way of life. I like democracy and everything it offers,' he said. 'But at the same time, we don't know ... If they say, 'Okay, this is your country, we can give you all that you need, and then we'll leave,' that would be great. But when you hear that American generals are coming to govern Iraq and that it will last one year, two years, three years, six months, this view, when you explain it to simple people, the majority, that will be very difficult. They can't digest it ... They'll say, 'Who's better, Saddam or the Americans? ... At least Saddam's from the country, and they're from the outside. I may understand it,' he added, 'but the majority won't.'" By the end of the book, even Fuad has grown painfully disillusioned with the Americans.

And Fuad is decidedly in the minority, even among educated Iraqis with sophisticated political views and no particular hatred of the United States. Wamidh Nadhme is a 62-year-old professor who is able to openly criticize Saddam without having nails driven through his head because he once visited the dictator in a Cairo hospital. On the eve of the invasion, Wamidh says, "I won't hide my feelings -- the American invasion has nothing to do with democracy and human rights. It is basically an angry response to the events of Sept. 11, an angry response to the survival of Saddam Hussein, and it has something to do with oil interests in the area." A year later, when the fighting in Fallujah broke out, Wamidh "took pride in the resistance ... A man steeped in honor and dignity, he, like most Iraqis, considered the fight legitimate, even heroic."

These are the "dead-enders," the "terrorist sympathizers"? Of the Bush administration's increasingly ludicrous pronouncements about the insurgents and their sympathizers, Shadid says, "It was as if acknowledging the enemy's significance called into question America's role as a liberator." No one who reads "Night Draws Near" will be able to ever again believe the White House's simplistic fables about who is fighting us in Iraq.

One of the more peculiar ironies of the Bush administration's case for war is that its officials, anxious to appear as enlightened, post-colonial liberators, refused to acknowledge the vast cultural and religious differences between Iraq and the U.S. and the problems those could create in installing democracy there. Take Iraq's tribes, with their fierce ethic of loyalty and honor. Of the most chilling episodes in "Night Draws Near" is one concerning the aftermath of an American raid in the Sunni triangle that killed three people. After the raid, an Iraqi informer walked among detainees, pointing them out to U.S. troops. Despite being disguised with a bag over his head, the informer was recognized by his fellow villagers by his yellow sandals and his amputated thumb. His name was Sabah. The town, Thuluyah, seethed with rage: Sabah had violated the unforgiving tribal code.

When Shadid asked some villagers what would happen to Sabah, he was greeted with stony silence -- men belonging to different tribes, potential enemies if the matter turned into a vendetta, were present and no one wanted to discuss it. Trying to be polite, one man softly whispered to Shadid, "Of course he'll be killed, but not yet." When Sabah fled, relatives of two of the men killed in the raid gave Sabah's family a choice: "Either they kill Sabah, or villagers would murder the rest of his family." That could set off a vendetta that might last for years.

Sabah's brother and uncle brought Sabah back to Thuluyah. The next day, his father and brother, carrying AK-47s, entered his room before dawn and took him behind the house. With trembling hands, the father fired twice. Shot through the leg and the torso, Sabah fell, still breathing. Some witnesses told Shadid that the father collapsed. Sabah's brother then fired three times, once at his brother's head, killing him.

Sitting with the father later, Shadid found himself unable to ask the question he knew that as a journalist he had to ask: Had he killed his son? "In a moment so tragic, so wretched, there still had to be decency. I didn't want to hear him say yes. I didn't want to humiliate him any further. In the end, I didn't have to."

"'I have the heart of a father, and he's my son,' he told me, his eyes cast to the ground. 'Even the prophet Abraham didn't have to kill his son.' He stopped, steadying his voice. 'There was no other choice.'"

(After Shadid's account of the killing appeared in the Washington Post, the U.S. military began searching for the father. In a speech Shadid gave in July 2004, he said the man was still in hiding, protected by his fellow villagers.)

Possibly the most poignant of Shadid's tales takes place far below such grand geostrategic concerns. It is the story of Karima Salman and her family. Karima, a desperately poor mother of eight, lived in a squalid, cockroach-infested apartment in Baghdad. The first story Shadid tells about her takes place before the war. Most of her family and friends had already fled Baghdad. She was exhausted, lonely, unable to pay the rent, faced with skyrocketing food prices. Her 21-year-old son, Ali, who had been working as a plumber, had been sent north days earlier to man an antiaircraft battery.

At their parting, movingly recounted by Shadid, Karima and Ali simply exchanged the basic phrases of Islam. "There is no God but God," she told Ali as he boarded a bus. "Muhammad is the messenger of God," Ali replied, completing the phrase. Her final words to him were prayers of farewell: "God be with you. God protect you." As she recounted their parting, tears ran down her cheeks. "A mother's heart rests on her son's heart," she told Shadid. "Every hour, I cry for him."

"Faith for Karima and her family was not a matter of religious zealotry," Shadid writes. "It was not even piety, really. It gave their lives cadence ... It spoke with clarity, offered simplicity, and served as a familiar refuge in troubled times." As Karima sat with her five daughters on old mattresses on a tile floor and waited for the war to begin, "in her voice was the hopelessness that forced so many in the once-proud city to put their faith and future in God's hands. 'We only have God,' she told me. 'Thanks be to him' ... To Karima, the war that had begun was a play; on its grand stage, people were mere actors. 'Life's not good, it's not bad,' she told me, as we sipped the bitter coffee. 'It's just a play.'"

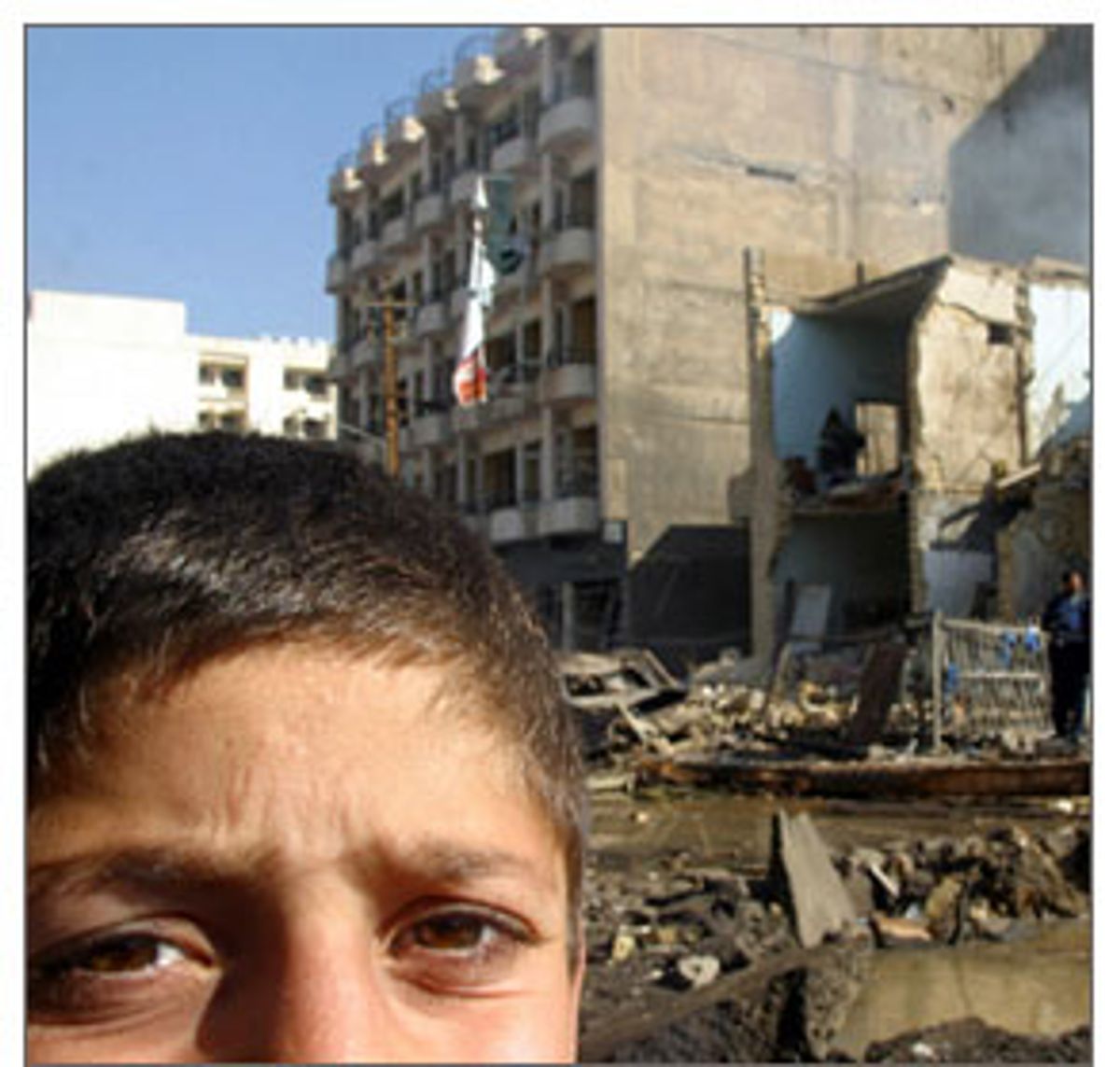

The fate of small people like Karima and her family, unknown, of no political consequence, is easy to forget as nations rush to war and powerful men plan and redraw maps. "Ordinary people are, as Karima recognized, only pawns on a giant board; if one or one thousand of them are swept off, no one notices." It is one of the functions of journalism, perhaps the noblest, simply to bear witness to these forgotten ones.

Karima's daughter Amal, about to turn 14, kept a diary during the bombing, invasion and occupation. In it, Shadid writes, "Amal never spoke of the war in political terms. There was only a young girl who did not understand why people were dying. Death in itself was wrong, whoever the victim; angry, she could see no justification." Looking at images of dead GIs, Amal wrote, "Why? What's the fault of those soldiers who were killed? What's the fault of the families of the dead, or their mothers, who must be crying over their sons? Why is this war happening? ... I saw on TV the injured in the south. I saw dead children, one without a hand, it was cut off. They were five or six years old, and the young men were aged 16 or 17, injured in their legs. How were they at fault? Why is there fighting? Oh God, have mercy on our dead."

As time goes on, Amal's voice grows surer, her questions deeper. "Her questions and her search for meaning were a measure of her own emerging freedom," Shadid writes. Amal's diary runs like a moving threnody throughout the book, heartbreaking and yet, in its portrayal of an innocent young girl coming of age, offering a ray of hope that crosses all boundaries.

Like virtually everyone who observed the post-invasion period, Shadid lays much of the blame for the disaster on the Bush administration's total failure to plan for the day after. "There was never really a plan for post-Saddam Iraq," he writes. "There was never a realistic view of what might ensue after the fall. There was hope that became faith, and delusions that became fatal." But Shadid goes beyond generalities to reveal how that failure actually impacted ordinary Iraqis.

The fortunes of the Salman family reflect the general collapse of Iraqi life under the occupation, a degeneration that was probably the most decisive practical factor in leading Iraqis to turn against the United States. The U.S. was never able to restore electricity and water to their prewar levels, which led many Iraqis, who thought of the U.S. as omnipotent after its lightning-quick military victory, to believe that the failure was intentional. (Shadid points out that it did not help that everyone remembered that Saddam was able to get the power more or less back within two months after the first Gulf War.) Having no power is no small matter in a country cursed with one of the most brutal summer climates on earth: As Amal tries to write in her diary, sweat pouring down onto the page during yet another interminable outage, her feet swollen from carrying buckets of water up several stories from the street, you can feel the whole country slipping away from the Americans, drop by drop.

Then there was the shocking, sickening collapse of security, which Shadid chronicles: Someone attempts to kidnap Amal and her sister; a thief pulls a man from his car at a market and shoots him for his satellite phone while a crowd of bystanders does nothing; a professor is riddled with bullets for no known reason. As Shadid puts it, "The looting had diminished but it was like a knife dragged across the city, digging wounds that would never heal."

Less well known than the destruction of Iraq's infrastructure and its security was the demise of simple civility, of the bonds that bound people together. While during the bombing the Salman family's neighbors helped them, a few months later, "all vestiges of this mutuality had by now disappeared; the crisis had gone on so long. The civility and solidarity that Karima and her family recalled from the invasion were nowhere to be found among their fellow Baghdadis. Now reigned confusion, chaos, and most often, pettiness. The same families who had prayed with them in war, creating bonds that had not before existed, refused to help Karima and her family hijack electricity from other buildings. At times, Karima's was the only apartment in the building that couldn't secure an electrical connection. The family had to sit in the dimly lit hallway if they wanted light." When Karima asked the family of her late husband's sister for money for food and rent, the family fought her and tried to get U.S. soldiers to arrest her.

The last story Shadid tells about the Salman family takes place a year after the invasion. Karima has found work as a maid at a hotel, taking home $33 a month. Ali made it home safely after deserting from the army; he found work serving tea in a real estate office, making about a dollar a day. As for Amal, she has grown confident enough to criticize both Saddam and the Americans. (Shadid points out the irony of the fact that it was the American invasion that made it possible for Amal to criticize the occupiers.) "If I say the Americans are better, someone asks, What have the Americans done? What have they done for us? All the Americans have done is bring the tanks," she tells Shadid. "If I said the time of Saddam was better, they say, What? If he didn't like you, he would cut off your head. He was a tyrant. I don't know what to say."

A few days later, Shadid returns and Amal continues their conversation. After opining that no government, Arab or foreign, is just, that all rulers are both good and bad, she adds, "There must be hope. Even the Quran says we must be optimistic. If you hope, you can get an answer. If you study more, you will find more success. If you have more hope, you can be assured of more and more progress. If not for my generation, then the generation that's coming."

After which Karima says softly to Shadid, "They're still young. They don't know what's ahead."

What lay ahead, we now know, was even worse. Shadid left in June 2004, returning in January 2005 to cover the elections. The window of hope offered by the elections quickly closed as Iraq descended into a hell of sectarian violence and insurgent attacks. Considering how bad the situation was even in the summer of 2004, it's hard to believe that Iraqis, despite their storied toughness, have not since suffered a collective nervous breakdown.

"Night Draws Near" does not assign blame for the ongoing tragedy in Iraq. Nor does Shadid attempt to compare the lives of Iraqis under Saddam with the lives of those under the U.S. occupation -- although many of his sources tell him that things are far worse under the Americans than under Saddam, and few if any say the opposite. In the largest sense, it is axiomatic that America is responsible for everything that has happened to Iraq since the invasion. But were the Iraqi people themselves partly responsible for their fate as well?

Shadid quotes several Iraqis who say that Saddam, with his endless wars and brutality, destroyed the Iraqi soul and spirit. Others say that Iraq needs a strongman to lead it, that it is simply not suited for democracy. What is indisputable is that over the years, Iraqis had become dependent on a Stalinist bureaucracy. "Some of the less charitable [Americans] grew angry at people they characterized as unprepared to help themselves," Shadid notes. "There was, of course, an element of truth in this. Iraqi society was battered and beaten down by wars and dictatorship. Sometimes it seemed that the initiative of Iraqis had been entirely vitiated by Saddam's government, which didn't sanction resourcefulness or originality and which fostered a dependency that many in Iraq were willing to embrace ... The U.S. administration may have complained that the Iraqis expected too much too soon, given the state of the country, the resources at hand and the challenges inherent in a postwar environment. But the Americans had to take, or at least share, responsibility for raising the people's expectations in the first place ... When [President Bush] promised that 'the life of the Iraqi citizen is going to dramatically improve,' his words were not forgotten. One of those who remembered was young Amal:

"'Please, tell us, when are we going to live a life of security and stability? Listen to us, hear us, you people out there, we have cried and shouted. What else can we do? ... They talk about democracy. Where is democracy? Is it that people die of hunger and deprivation and fear? Is that democracy?'"

Was the American intervention doomed from the start? Or if we had made all the right decisions -- preventing looting, restoring services, not disbanding the army, treading lightly in the Sunni triangle -- could it have worked? Shadid is agnostic at best. "Another scenario for life after Saddam was perhaps possible: the ruler falls, to the joy of many; a curfew is imposed in the capital, and a provisional government is quickly constituted; basic services -- electricity, water, and sewage -- are rapidly restored; security, at times draconian, is imposed in the streets; and aid starts pouring into Baghdad, as foreign and Iraqi companies compete for the bounty of the reconstruction of a country awash in oil. The occupation might have unfolded that way -- but it didn't."

"Perhaps history condemned the project from the start," Shadid goes on. "A grim warning lay in Iraq's modern record, shaped as it was by deprivation -- Saddam's tyranny, his wars, and the expectations of Baghdadis that they deserved better. The Iraqi impression of America was no less a problem. Whatever its intentions, the United States was a non-Muslim invader in a Muslim land. For a generation, its reputation had been molded by its alliance with Israel, its record in the 1991 Gulf War, and its support for the U.N. sanctions. Not insubstantial were decades over which the United States had grown as an antagonist in the eyes of many Arabs. Iraq had long been removed from the Arab world, isolated by dictatorship, war, and the sanctions, but it remained Arab."

Observing American troops entering Baghdad for the first time, Shadid is nearly overwhelmed by the historical magnitude of what he was witnessing. In an eloquent passage, he writes, "The United States now controlled Iraq's destiny; we would now decide its fate. And we understood remarkably little about it. Deep down, I worried we would never try to know it, either. At best, we would try to force it into our construct and preconception of what a country should be. At worst, we would not care, giving in to overly emotional impressions distorted by differences in language, culture, and traditions, and by conceit. In between, the ambiguity that so defined Iraq for me -- the uncertainty, the ambivalence, the legacy of its history -- would become too complicated to unravel."

Shadid has helped us understand. Cutting through cultural and religious differences, he is able to convey the humanity of the Iraqi people. This may seem like a modest achievement, but it is in fact a major one. In an unspoken rebuke of the Clash of Civilization theorists who see cosmic gulfs between cultures and monstrous totems instead of knowable beliefs, he walks through the streets, talking and listening to people. His Iraq is a land of human beings, people who desire a decent life, who raise children and go to work and laugh and cry. They have their own religion and culture, which they do not want anyone to trample. There are fanatics and criminals among them, but they do not define who Iraqis are. Without their consent, we freed them from one nightmare only to plunge them into another one. They have suffered for far too long.

The day after Saddam fell, I wrote a piece of celebration. It concluded, "Those who opposed this war in part because they feared what it would do to the Iraqi people must now make every effort to protect and raise up those people. And to do that, they must pay attention to what is happening to them -- the good, the bad and the in-between. This is the most compelling reason to celebrate the end of Saddam. Call that celebration a leap of faith, if you will -- but you could also call it a binding contract, American to Iraqi, human heart to human heart. We smashed your country and we killed your people and we freed you from a monster: We are bound together now by blood. We owe each other, but we owe you more because we are stronger and because we came into your country."

Through inexcusable incompetence and folly, we broke that contract. We owed the Iraqi people better. "There must be hope," Amal said, and her words must not go unanswered. The tragedy is that there may no longer be any way for us to help her. The future of Iraq is unknowable, and history's judgment on America's war cannot yet be rendered. But if that judgment is harsh, we will carry the shame of it forever.

Shares