There are so many new shows about divorced people this

season, prime time is starting to mirror the actual divorce

rate. Yes, TV has come a long way since "The Brady Bunch"

coyly created a blended family by way of double-spousal

death. Nowadays, divorce dares speak its name -- loudly.

Failing at marriage is not (usually) portrayed as a scandal

or a moral flaw; on sitcoms from the old "Designing Women"

and "Cybill" to "Frasier," divorced people are, if not

thrilled with the single life, then at least happy to be rid

of their exes' baggage.

The fall's new drama series about divorce, though, are more

somber and reflective. Aimed mainly at divorced working

mothers, ABC's "Once and Again" and CBS's "Family Law" and

"Judging Amy" make a decent attempt to depict what divorce

does to a family (or at least to a white,

upper-middle-class family). These dramas are a banquet of

messy emotions -- anger, resentment, desire for revenge,

relief -- topped off with a big fat dollop of guilt, the

cherry on the sundae. "Every minute I'm here, I'm worried

about what's happening with my kids, and when I'm with my

kids I'm worried about what's happening here, and I can't do

all this!" exclaims the newly single mom-attorney of "Family

Law." Telling his kids that their parents were breaking up,

confesses the divorced suburban dad of "Once and Again," was

like taking a baseball bat and "having a good solid whack at

both their heads."

But while all of these new dramas have scenes in early

episodes where divorced parents are nearly undone by guilt,

they also have scenes where the heroines pull it together

and fiercely renew their vows to have it all -- "all"

meaning career, motherhood and freedom. Shows like "Judging

Amy," "Family Law" and "Once and Again" may be the perfect

fantasy shows for divorce-torn times; their heroines aren't

as glamorous as Alexis and Krystle and Amanda, but their

revenge tastes just as sweet.

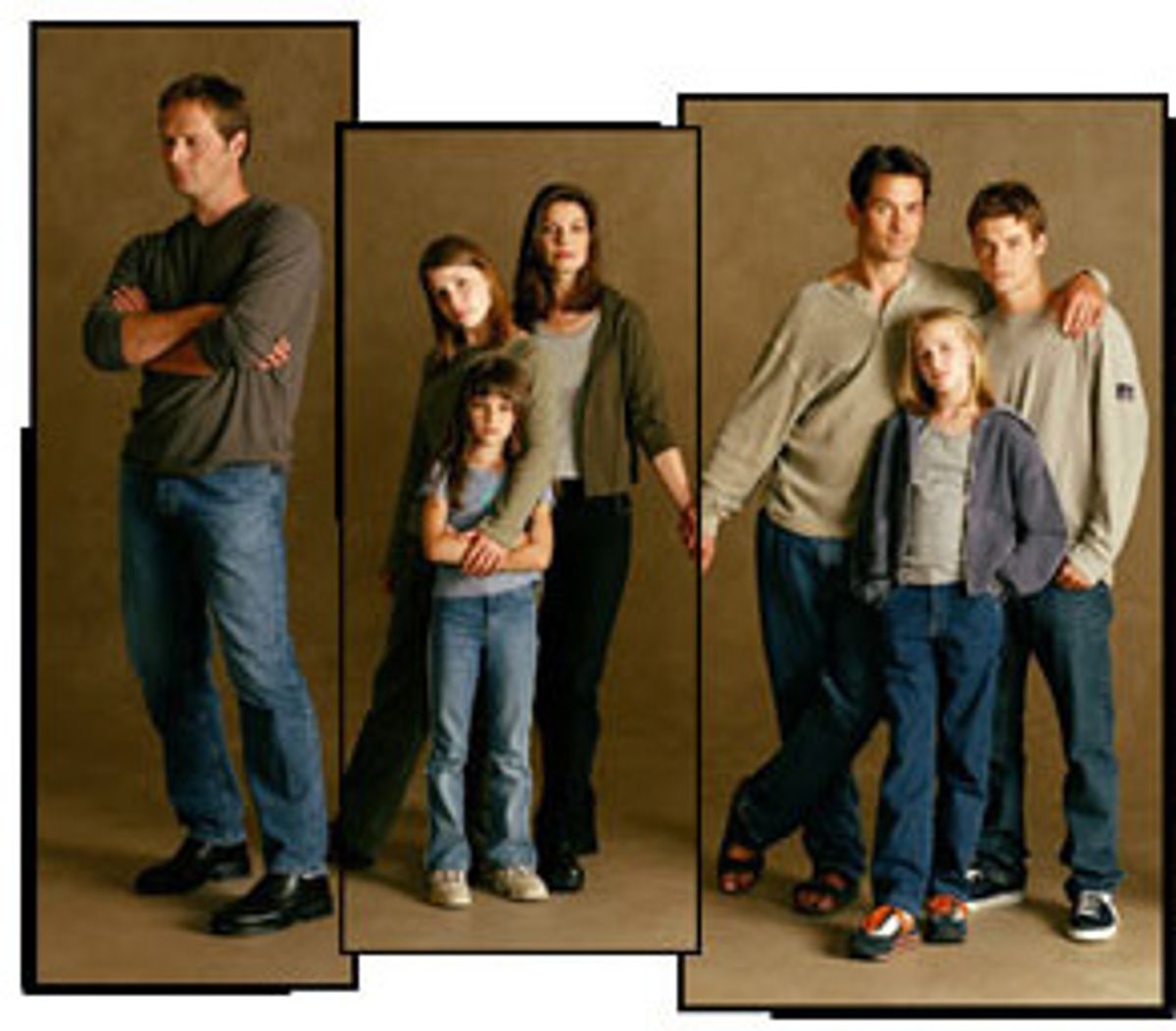

The most elegantly crafted show in this trio is Marshall

Herskovitz and Ed Zwick's "Once and Again," which looks a

lot like what Herskovitz and Zwick's "thirtysomething" might

have become if it didn't get canceled before Hope and

Michael reached the breakup they were obviously heading

for. A decade ago, Herskovitz and Zwick based

"thirtysomething" on their own marriages, which were

undergoing the tests of parenthood, career success and

stay-

having watched "Once and Again," that Herskovitz is now

divorced. Those guys are so plugged in to the boomer

zeitgeist, it's scary.

"Once and Again" has the duo's unmistakable imprints:

lyrically written dialogue that makes white middle-class

angst sing, emotionally voyeuristic shots of characters

being pensive, snuggly folksy background music, gold and gray autumn light.

Herskovitz and Zwick haven't lost the touch for eliciting a

deep, visceral identification with their characters; whether

that makes the characters, or us, stereotypical is open to

debate. The pilot did a fine job of portraying the

existential terror of an over-40, SUV-driving soccer mom

(Sela Ward) and football dad (Billy Campbell), whose dreams

have fallen apart; it did an even better job of depicting

their confusing, exhilarating rush of emotions at facing new

romantic possibilities.

Lily Manning (Ward) and Rick Sammler (Campbell) have teens

at the same high school. They eye each other while unloading

the kids one morning, then awkwardly chat during a chance

meeting in the school office. In the Sept. 21 pilot, after

much agonizing, he called her for a date, then another. They

had to speak furtively on the phone, because their kids were

always around listening; they necked in his SUV like

teenagers, because she was afraid to take him inside her

house, lest they get caught (they did, by her ex-husband and

two daughters). "Once and Again" has an enticing parallel

going; Lily and Rick are behaving like horny teens again

(they've shared some of the sexiest TV kisses in a long

time) at the same time his son and her daughter are

suffering their respective growing pains.

"Once and Again" (which occupies the "NYPD Blue" time slot

until that show returns Nov. 9) is not without its

drawbacks. Herskovitz and Zwick have come up with this

gimmick where Lily and Rick talk directly to the camera in

scenes shot in black-and-white; it's supposed to show them

revealing the innermost feelings they're unable to reveal to

each other. The limitations of this device became apparent

pretty quickly in the pilot; it's pretentious and annoying

and it breaks up the flow of the story (I use the term

"flow" loosely, because the show doesn't flow as much as

float). Also, Lily's daughter Grace (Julia Whelan) has been

compared by some critics to spunky Angela Chase from "My

So-Called Life," which is absurd. Grace is a whiny wet

noodle of a girl; she has anxiety attacks when her mother

leaves the house, she thinks she's fat and she can't bear that

she may actually have to interact with Rick's hunky jock

son, Eli, some day. Grace is an all-too-realistic source of

divorce guilt for Lily. In the pilot, when Lily finally went

tough-love and told her daughter, "I'm not going to let your

fear dominate this house anymore," you could almost hear

shouts of "You go, girl!" welling up from the suburbs of

America.

But for "You go, girl!" sentiments of the man-dissing kind,

it's hard to top the Sept. 20 pilot of "Family Law." In the

first scene, Los Angeles family law attorney Lynn Holt

(Kathleen Quinlan) was dumped by her husband/law partner;

not only did he run off with another woman, he took most of

the firm's lawyers and clients with him, leaving Lynn with

their two kids and no income. Lynn was floored, but soon the

survival instinct kicks in and she's stealing back clients,

hiring a flamboyant divorce lawyer played by Dixie Carter

("I hate men. And I play very dirty"), scraping "men" off

the door of the bigger bathroom and turning the urinals into

decorative planters. "Family Law" is the most

male-unfriendly show since "Designing Women"; it has a

symbolically perfect time slot opposite "Monday Night

Football."

Lynn's personal crises notwithstanding, "Family Law" is

mostly a workplace drama; the cases Lynn and her loyal

associate Danni (perky Julie Warner) took on in the pilot

represented the various ways marriages and families can go

wrong -- ex-spouses squabbling over the ashes of a pet, a

recovering junkie who wants to get her sons back from foster

parents. Written by co-creators Paul Haggis and Anne Kenney,

the pilot episode was unabashedly female-centric (the

central theme, echoing through Lynn's situation and the

junkie-mom story line, was "What makes a mother?"). But

Haggis, who worked on "thirtysomething" and was the guiding

hand for the very dark, twisted CBS crime drama "EZ

Streets," has juiced "Family Law" with surprising edginess,

stinging humor (used sparingly -- this is a traditional

drama, not a comedy-drama thing) and the brisk pacing of a

cop show. "Family Law" is still a women's show, don't get me

wrong, but there are no angels, no ghosts, no fantasy

sequences. It's one of the few shows in recent years where

women's emotions and lives are deemed dramatically

interesting and important enough to stand alone.

It's one of the mysteries of network programming why CBS

decided to launch two female-aimed dramas about divorced

mothers who work with issues of family law. Like "Family

Law," "Judging Amy" is set against the backdrop of broken

homes, custody battles and child abuse. And like "Family

Law," "Amy" looks at the bright side of its heroines'

marital break-ups -- divorce isn't swell, but a family can

go through a lot worse.

Many similarities have been pointed out in the press (mea

culpa) between "Judging Amy" and NBC's hit "Providence,"

about a single Los Angeles plastic surgeon who chucks her

practice, moves back home to Rhode Island, becomes a family

doctor and communes with the advice-dispensing spirit of her

dead mother. In "Judging Amy," Los Angeles corporate lawyer

Amy Gray (Amy Brenneman) gets divorced, accepts a judgeship

back in her hometown of Hartford, Conn., and moves

there with her 6-year-old daughter. They live with Amy's

widowed mother, Maxine (a gray-haired, crotchety Tyne Daly),

once a pioneering social worker and working mom, now a

dogmatic busybody puttering unhappily through retirement.

Maxine dispenses advice, but Amy has to hack through layers

of crusty mom-speak to glean it.

In tone, "Judging Amy" isn't much like the soft-focus,

sentimental "Providence" at all. Writer-producers John

Tinker, Barbara Hall, Bill D'Elia and their intelligence-radiating star

(who also gets a producer credit) have turned

out a crisply entertaining drama that's as crammed-full as

Amy's docket. The show's concerns include divorce and

combining career and single parenthood, of course, but also

aging, growing up, the search for personal fulfillment,

parents who can't let go and the volatile relationship

between mothers and daughters (Brenneman and Daly are

well-matched sparring partners).

Brenneman's Amy is believably overextended trying to smooth

daughter Lauren's transition to their new life while

simultaneously learning the ropes as a family court judge.

Amy is cranky, she's tired, she has doubts and guilt about

what leaving her marriage is doing to her kid. And she's got

to do it all under the long shadow of Maxine, a living

legend. But Amy is a true working-mom heroine. She takes too

much on, then miraculously finds a way to deliver; to fall

apart would be giving ammunition to those she feels are

sitting in judgment of her -- her mother, her daughter, her

ex, her boss, the stay-at-home mothers at Lauren's school.

The show's central irony is that Amy feels like she's in

over her head as a judge who has to decide cases based on

the best interest of the child when she's not even sure

what's best for her own child. Amy has yet to figure out

what Maxine has learned about decision-making: Look

authoritative and fake it.

Shares