Stories by Salon News and others that attempt to connect the dots in unflattering ways between George W. Bush and funeral home mogul Robert Waltrip have been making the rounds of funeral directors' fax machines all over the country. The stories contain unsavory implications about state employees, depositions, big-bucks campaign donations and the good ol' boys. Does anyone else hear an echo here?

Like most of our fellow Americans, we funeral directors know very little about Bush beyond, of course, his huge campaign war chest, the unstoppable juggernaut of his candidacy and the apparent inevitability of his nomination. Since most of us are small-business types with Republican tendencies and hometown duties, we are glad that the media and the politicos are taking care of matters such as these for people such as us.

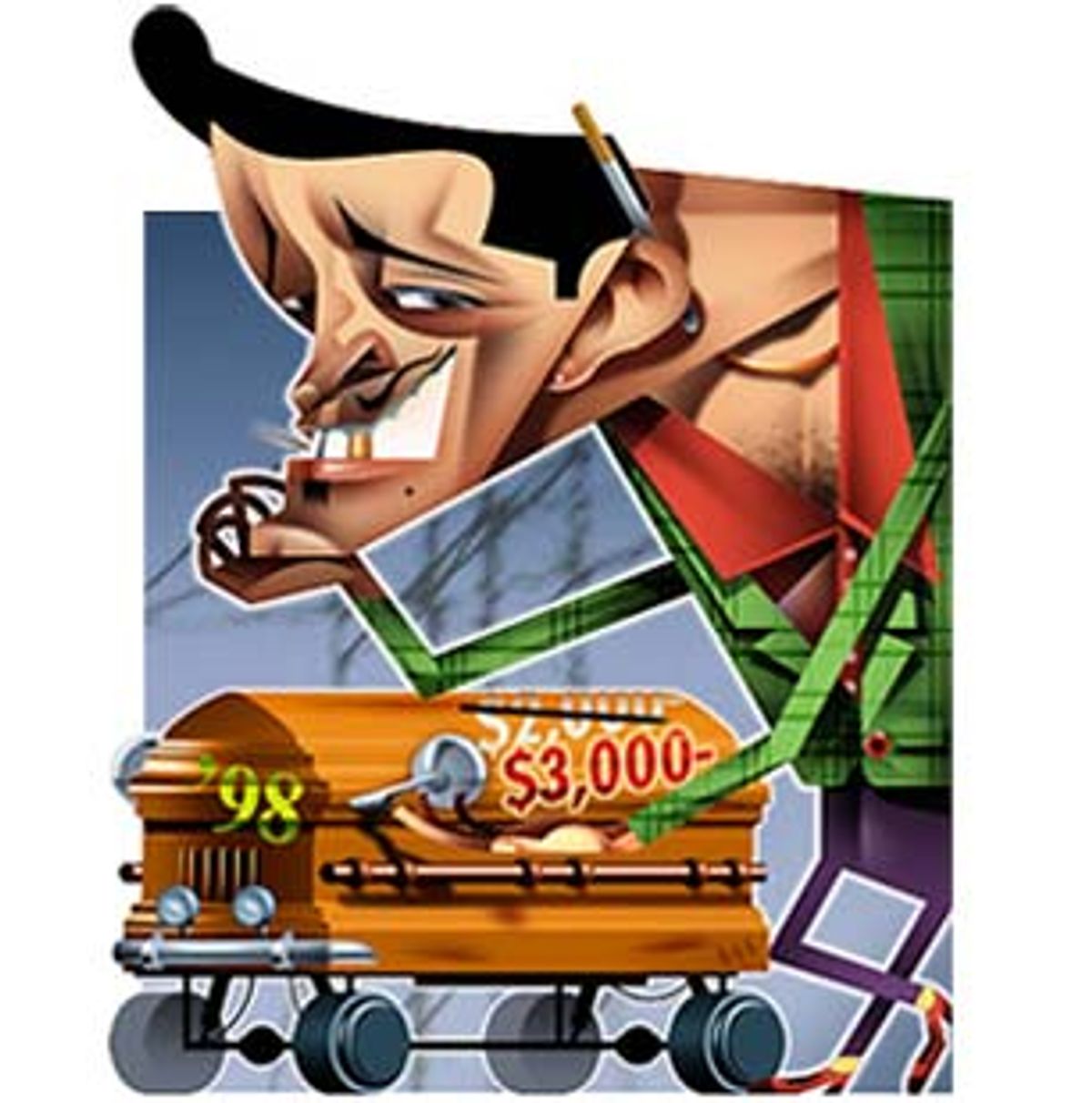

But Waltrip of Service Corporation International in Houston, is no stranger to us. He and SCI are to funeral service what McDonald's is to the local diner: a multinational mergers-and-acquisitions firm that has bought up funeral homes and cemeteries on five continents, including something like one in five here in the good old USA, where good old George W. will maybe be president if everything goes according to plan.

Of course, Waltrip is a Big Mac that comes disguised as the burger you get from your local diner. SCI has made a fortune trading on the long-established names of local funeral directors, who never made in a year what Waltrip has given to the Bush campaigns. To be sure, these firms sold willingly for good money with their eyes wide open. For many funeral directors, as for many Republicans, it all seemed unstoppable, inevitable -- SCI was everywhere, lavishing free booze and finger food on us at our state and national conventions, offering cash and stock options and a "bigger is better" view of the future.

This is not evil. It is the late-century American way: to merge and acquire, to buy and sell. And there is nothing inherently wrong with corporate ownership, nor anything especially noble about independent ownership. In every field, there are sloppy independent operators and exemplary corporate ones.

In practice, however, they are organized around essentially different principles. The publicly traded, corporate enterprise is accountable to the international headquarters, the sales quota and the stockholder, while the independent is accountable to the local consumer, including very often the local loan officer. The privately owned firm cannot attribute its prices to some distant "home office" or the "district manager." It cannot blame shortfalls in service on "company policy." The privately owned firm must make up in local public trust what it lacks in multinational corporate cover.

For independent companies, market share -- present and future -- is guaranteed by reputation, while corporates place more stock in pre-need sales. Independents count on the name on the sign. Corporates count on the money in the bank. This is why the hard-sell pre-selling of funerals has increased in direct proportion to consolidation within the funeral service industry. Pre-arrangement is as old as the pyramids, pre-funding as old as the money stuffed in the mattress. But pre-selling -- the junk mail, telemarketed, briefcase bargain of the memorial counselors and conglomerates -- has turned the funeral from an existential event into a retail one. As more package deals are proffered and pre-sold, the public is quite clearly buying less.

Still, it has seemed to many funeral directors that the only choices were to sell hard or to sell out. SCI, along with Loewen (its recently bankrupt Canadian competition) and Stewart Enterprises from Louisiana, has been wildly successful at persuading funeral directors and their associations that the future belongs to them. The bottom-line sensibilities that turn every sadness into a sales op have convinced a portion of the public that funerals and funeral directors are more trouble than they are worth, and a little like cheeseburgers: all the same.

We are not. The name on my sign, like the names on most, is not Funerals 'R' Us or Best Buy Burials or Mortuary Express. The name is mine, my family's, my father's and mother's, my brother's and sister's, our son's and daughter's. When we serve the families in our town well, they can ignore us, personally. When we don't, they can complain, personally. It is better consumer protection than the FTC or CNN or anyone in Houston can provide. People talk. Our lives and livelihoods depend on it. The name is worth more than the brick and mortar, the rolling stock or any money in the bank. It is the only one we have. We cannot get another. It determines whom we hire, what we sell, for how much, what we say, who we are and what we do. Home office is here -- where the buck stops, where the phone rings in the middle of the night.

And because, like a mother and a father and the love of one's life, a funeral is a thing we only get one of, funerals do not respond well to efficiencies, conveniences, downsizings, economies of scale or uniformities -- all much valued in the corporate world. A funeral is not a great investment; it is a sad moment in a family's history. It is not a hedge against inflation; it is a rite of passage. It is not a retail event; it is an effort to make sense of our mortality. It has less to do with actuarial profits and more to do with actual losses. It is not an exercise in salesmanship; it is an exercise in humanity.

Waltrip and his "death-care professionals" ignore such distinctions at their peril. The Main Street consumer, the Wall Street investor and the mainstream press have connected these dots. They seem to be voting in their various ways against globalization in the mortuary trades. Maybe Mission Control shouldn't be in Houston. Maybe the home office should be closer to home. SCI's stock has fallen from the 40s to the mid-teens this year. A portfolio of "death-care" stocks (SRV, STEI, LWN, HB, YRK) is down more than 60 percent from last summer's values. The New York City Department of Consumer Affairs has urged the state attorney general to prevent further acquisitions by SCI in that city.

Lawsuits against SCI have been filed by disgruntled investors, outraged families and now, it turns out, the state of Texas' former chief funeral regulator, Eliza May, who claims she was given her walking papers for investigating Waltrip's enterprise on reports of unlicensed personnel embalming bodies. The allegation is that Waltrip complained and the investigation went away. And then the investigator did too. Of course, no one wants to connect the dots between May's dismissal and SCI's paying George Bush Sr. $70,000 for a speech to the International Cemetery and Funeral Association or donating $100,000 to his presidential library or helping George W. with his White House aspirations.

Here in Middle America, we funeral directors are not entirely stunned that big business, big money and now big politics may all be aligned against us. We are long accustomed to the slings and arrows.

Candidate Bush will not much miss the funeral directors' vote. We are tiny in the firmament of influence. Points of light, his father called them -- who deal with neighbors more than national concerns. Still, skeletons in one's closet notwithstanding, all politics, like all funerals, are local.

Shares