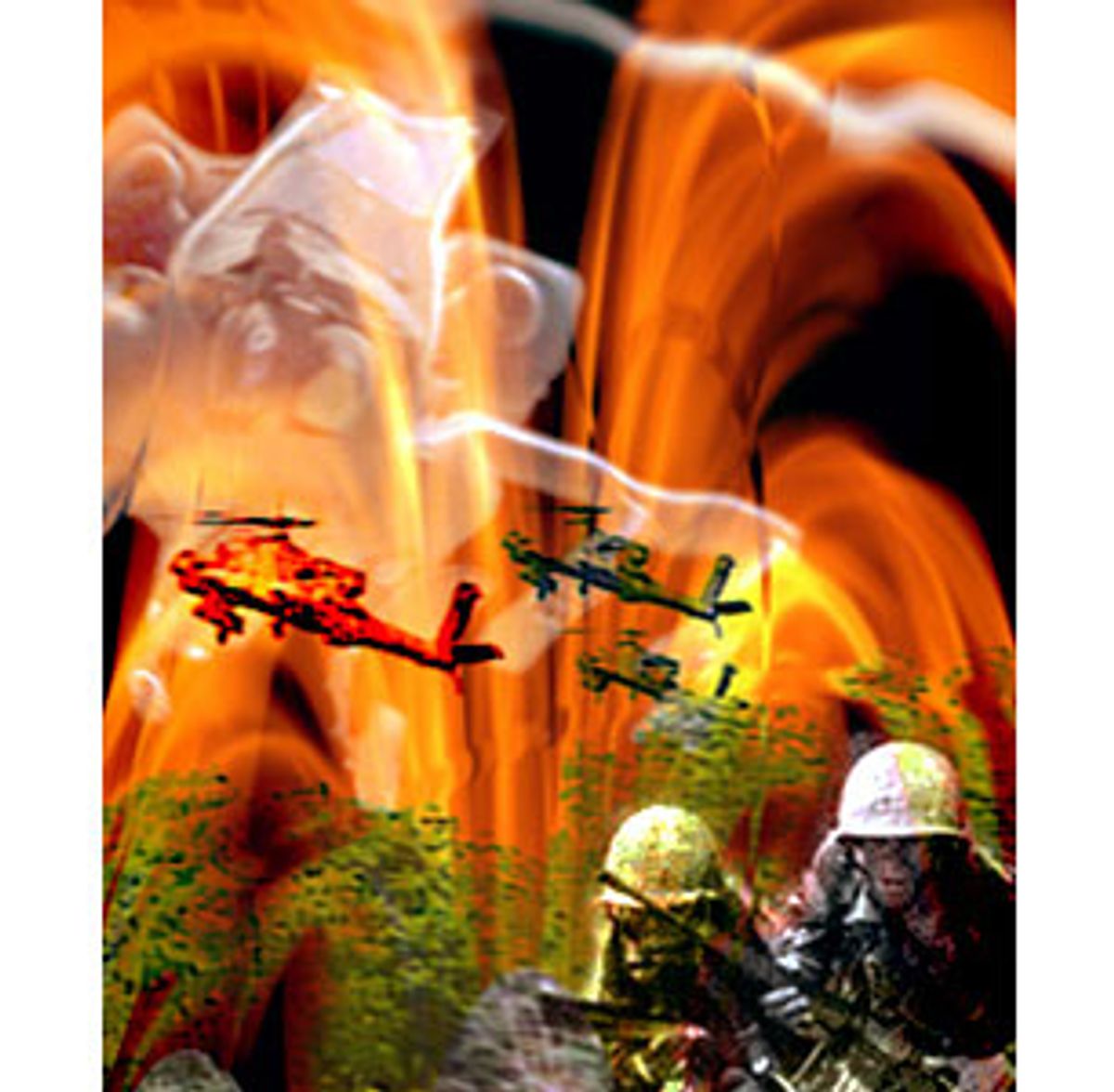

Francis Ford Coppola's "Apocalypse Now" renders Vietnam as the Inferno, with a psychedelic swirl of helicopters, flames and fog. An arbitrary attack on a tiny Viet Cong village appears to have an entire squadron of air cavalry supporting it. A quartet of needle-nosed jets finishes the job with napalm. The firepower is stupendous. Its force is heightened even further by "The Ride of the Valkyrie" on the soundtrack. This is Coppola's Wagnerian extravaganza, with streamlined, fire-breathing dragons.

The movie opens in a soft blue haze: a junglescape enveloped in a smoky aura that bathes the scenery in a golden pseudo-dawn. Helicopters swoop through the images, seemingly close enough to touch, but insubstantial, like shadows. Palms burn abruptly with napalm, not with a dramatic burst but as naturally as sunflowers opening up to daylight, while the Doors' dirge "The End" plays out against the blaze. Suddenly, the choppers' propellers become the blades of a Saigon hotel-room fan -- and we enter the mind of Willard (Martin Sheen), who will soon trek through a Southeast Asian heart of darkness in search of the military madman Kurtz (Marlon Brando).

When the film premiered in 70mm stereo in 1979, this deliberately elusive opening put many viewers under a hallucinatory spell. Years later, even those who resisted the film (like I did) find its brilliant and insidious meshing of imagery and sound sneaking into their heads when they think of Vietnam.

None of the movie's sounds is more indelible than the roaring, buzzing and whirring of its helicopters. And Walter Murch, who both designed the sound and edited a healthy chunk of the movie (from the opening through a My Lai-like attack on a civilian sampan), says that the choppers' audiovisual potency was built right into the movie's DNA.

I spoke with Murch at the San Francisco editing rooms of Coppola's company, American Zoetrope. Amazingly, Murch was once again working on "Apocalypse Now." The French film company Canal Plus has funded what Murch calls "a fishing expedition." He and Coppola are sifting through outtakes that had been kept in underground storage to find deleted scenes worthy of inclusion in an expanded edition that is being released in August in theaters and will ultimately wind up on DVD. The only additional footage in the current DVD is the destruction of Kurtz's compound, which ran under credits at the close of the film's 35mm prints in '79. On the disc, Coppola explains that he never intended the conflagration to complete the action of the film. Murch stole time away from his recon mission to explain how he and his collaborators originally came up with the film's eerie and illuminating sounds.

When did you and Francis know that you would key so much of the movie off the sound of the helicopters?

It was something that came up long before the film ever got made -- back when George [Lucas] was going to direct it. There was a lot of discussion between George and me, and between us and John Milius, who was writing the script, that what made Vietnam different and unique was that it was the helicopter war. Helicopters occupied the same place in this war that the cavalry used to. The last time the cavalry was used was in World War I, which demonstrated that it didn't work anymore. In World War II there was no cavalry. Then we got the cavalry back, with helicopters, to a certain extent in the Korean War, and really got it back in the Vietnam War. The helicopters were the horses of the sky -- the whole "Valkyrie" idea came out of that discussion. And, of course, we thought of the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. The cavalry-horsemen-Apocalypse thing was bred in the bones of the project.

The beginning of the film was a trigger for the psychic dimension of the helicopters. Later on, when you get into the attack on the village [when Robert Duvall's ramrod Col. Kilgore tries to clear a VC-held coastal town], it's dramatic and it's fantastic, but it is fairly much "what you see is what you hear." Whereas at the beginning of the film it's some drunken reverie of this displaced person, Willard, who is trying to bring himself back into focus. There are fragmentary images of helicopters, then he comes more and more back into his abysmal reality -- this stinky hotel room in Saigon -- and we get the fan.

That connection, between the helicopters and the fan, was latent and waiting to be done. For me, the moment when it came to be done was like one of those moments when Kennedy was shot: I remember I was at the KEM [a horizontal editing machine with two large screens and two soundtracks], early on in the assembly of that scene, when I put a helicopter sound over that fan. Suddenly it sounded right. I believed the fan was making that noise, which is what Willard believes. So I felt that if I could believe it, as the "seen-it-all" editor, then it would have that effect on an audience. And if we could have that effect, then we could put the audience in the place of that person.

The helicopter sound isn't just a combat sound in this movie. It's like the defining sound in World War II movies of the German police cars ...

Duh-dah-duh-dah-duh-dah ...

Right -- so the sound of helicopters conjures up this sense of an existential prison. It's like a jail sound that envelops Willard periodically.

Right. But all of this was latent. Even the idea of starting with the shot we started with. That was something that came to Francis when he was looking at dailies. The film never began that way in the script. He was looking at the napalm drop when Kilgore calls in the planes to drop napalm on the jungle so that his guys can surf. There were six cameras shooting. The sixth camera had a telephoto lens and was shooting at, oh, 120 frames per second. Francis saw this shot from the sixth camera and recognized something about how the jungle was compressed and flattened by the telephoto lens, and about how the helicopters, because of this visual compression, just sort of slide sideways across the frame in a very dreamlike way. That's when he got the idea, "This is Vietnam," just by looking at this scene that explodes in fire. There was something dramatic about these three elements of green jungle, helicopter and fire.

Then we took things from the end of the film, and put the Doors' "This is the end" and worked that in -- so that somehow the end of the film is contained in the beginning. And then, once that was in place, there were shots done specifically to feed that thought. The images of Willard in his room alone drunk were actually character-rehearsal shots. Francis had the notion that if you wanted an actor to investigate a certain part of a character in an improvisational way, you turn film on it, even if you think the film will never be used, because it makes the actor wake up -- after all, it could be used, resources are being expended. What you wind up with has a different feel than if it were just an actor and a director alone in a room saying, "Let's investigate" (although some of that is done, too). Even those shots at the time were not meant to be in the film, but such amazing things came out of it that we felt, all right, let's put that shot of the helicopters and the jungle together with this stuff and see what we need to get from here to there.

As I said, the whole idea of the helicopter sound of the war wasn't a discovery; that was talked about in 1969. But Francis made the decision to make this film quadraphonic [or quintaphonic]. Essentially the format we established for "Apocalypse Now" is now the standard for DVD and any big Dolby Stereo film: three channels in the front and then two channels in the rear and then subwoofers. And helicopters are ideally suited to that, because they fly and move around and hover. So it's a perfect format for a helicopter movie, compared to, say, a submarine movie, or a boat movie, or an airplane movie. Helicopters can position themselves and swoop and go in circles; they are kind of circular beings.

I think people were impressed because there was this whole new way of listening to movies and it matched the main aural subjects, which were helicopters. Then you had the fact that the film is told from a particular person's point of view, that it presents the war as seen by Captain Benjamin Willard. And we establish right from the start that the helicopter sound is part of what makes you identify with Willard -- it subjectivizes your experience, so it's not just an impressive technical sound, it's got a psychic dimension that is very deep. So you have all this working at different levels at the same time. Some of it was deliberately investigated right from the beginning, even when there was a different director, so it was inherent in the script. But a lot of it was also discovered in the process of making the film.

I remember, having edited the attack scene, I knew that there was rarely a moment when you were seeing more than [approximately] eight helicopters. Francis had gotten these helicopters under contract from the Philippines' army; at night they were repainted and sent down to the south to terrorize the Communist rebels. We never knew the next morning how many would come back and in what condition. And they had to be repainted in American colors -- it was an unbelievable process.

We didn't have that many helicopters, but when you edit a scene, you cut it so that there seem to be eight helicopters over there, and -- here come another eight from this direction, and here are four more flying overhead from the north, and here are three more from the south. So eight plus eight plus four plus three is 23! And the funny thing is, that when I was cutting it, that didn't occur to me -- I knew it instinctively, but it wasn't conscious stuff. Then, when I set out to mix the film and talked to the sound editors, they said, well, these are coming from there, and you have to keep those sounds going when you bring in the other ones. It was like coming upon the Grand Canyon after wandering in the forest.

I realized how immense this was really going to be. You are hit by the immensity of that sound, but visually there's a tricky thing going on, because you're never looking at more than eight at one time. That was another discovery -- and, again, it was latent. You only confronted the monumentality of this picture when you were doing it. And the movie became particularly monumental because of the nature of the format we were dealing with. Nobody else had ever done it before: We were grappling with sound in three dimensions.

I'm old enough to remember the black-and-white TV footage and the choppers being part of that, but I don't have a specific memory of the sound from that footage. Did you in the late '70s?

Again, it was probably there but latent. The soldiers that we talked to would talk about it. And there was a wonderful documentarian who had worked in Vietnam -- Eugene Jones was his name. He said you always heard these whirling sounds: They permeated everything.

Was the recording of the helicopters done on location in the Philippines?

No, that was done at a Coast Guard station up in Washington. We did three days of recording there. The Coast Guard was very cooperative. We went up with a list of what we needed, and they had all the different kinds of helicopters. The LOACHes, some acronym for these buzzy little helicopters, and the HUEYs, another acronym [for the war's main helicopter utility vehicle], and a third one, with the double rotors on it, which makes a thuddier sound. A great thing about helicopters is that their variety has a musical element to it. So the LOACHes were the high strings, and the HUEYs occupy the middle range, and then these helicopters with two blades, fore and aft, have a huge thwud-thwud-thwud sound to them.

I'm surprised the Coast Guard cooperated; all we read about at the time was that no branches of the American military would help you.

That is basically true, and it's one of the most interesting things about this film. I can't think of another film with a military theme done on this scale that didn't have the cooperation of the military. And no matter how neutral a presence, if there is a military presence on the set -- Colonel Somebody -- when you shoot the scenes, it inevitably sets a tone. There was none of that here -- in fact, just the opposite. Once the word got out that this film was being made in the Philippines, and that the Army was not cooperating with us, it attracted all these real-life Captain Willards like a magnet. They were people who had gone Missing In Action but were still alive and living anonymously on some island in the Philippines, doing bush-piloting or beachcombing. They came to this film and hovered around it and said, "No, here's how it would happen." So we did have advisors, but an opposite kind of advisors from the ones you'd normally get on a military film, who will naturally give you what the military wants you to put out.

Even the most realistic sounds in the film are sometimes hard to identify; they come at you as part of an integrated scheme.

That's partly because we took those realistic sounds and deconstructed them on synthesizers. One more wonderful thing about the way a helicopter sounds is that it has a different articulation as it passes by. You'll hear five or six different things going on when you get into different spatial relationships to it -- sometimes you'll hear just the rotor, then you'll hear just the turbine, then you'll hear just the tail rotor, then you'll hear some clanking piece of machinery, then you'll hear low thuds. The helicopter provides you with the sound equivalent of shining a white light through a prism -- you get the hidden colors of the rainbow. So we would hear a real helicopter at any point and say -- listen to that! Let's see if we can synthesize just that! And using a synthesizer we created artificial sounds to mimic the real sound.

We formed what became known as "the ghost helicopter" out of this, which was sort of an aural Lego kit. You could put the helicopters all together and they'd sound very realistic. But then you could take them apart and play any one of them individually, a single helicopter on multiple tracks, and that's what the film begins with. That sound -- that whoop-whoop-whoop-whoop-whoop sound -- is the synthesized blade sound. And in isolation it had this dream-like quality.

We used lots of isolated sounds in various places, wherever we felt we needed to color the realistic sound and make it hyper-real. Throughout the movie, the helicopter is positioned between realism and hyper-realism and surrealism. It can slide anywhere on the spectrum. In musical terms, we thought of the helicopters as our string section.

Small arms fire would be the woodwinds, I guess. The "Valkyrie" scene has the Wagner music in it. It has choppers in it. And it also has the small-arms fire, which occupies a different region. Then there are the artillery sounds -- the mortar fire -- and a vocal part of the sandwich, from the sounds the people are making. Another layer is the clinkity-clink sounds of people moving around. Then there's a layer of winds and fire and leaves blowing.

There were a lot of instruments in the film. The soldiers we talked to said that anywhere you went in Vietnam you could hear some low artillery going on. Thunk-a-thunk-thunk-thunk. That has a kind of timpani quality to it. But it also sounds like a heartbeat. We positioned it "way over in the next valley," so to speak. We put it in when Willard and Chef [Frederic Forrest] were coming in on the tiger. Before you know that there's a tiger in the jungle, you hear naturalistic sounds of the jungle. But underneath it is this thunk-a-thunk-thunk, thunk-thunk-thunk.

What's interesting when you're working with image and sound is to stretch the content of what you're looking at to the breaking point. In the case of the tiger scene, we stretched it to the point where nothing that you're looking at has anything to do with what you are hearing. Under these circumstances people tend not to hear sound consciously. But they process it nevertheless, and it has the effect of a heartbeat. If you stopped the film and asked, "What's that sound?" -- people would come to a certain level of consciousness, and say, "Oh, it must be distant artillery." But they don't: The sound operates at this subcutaneous level.

In the Do Lung Bridge scene, what was interesting was to create a sonic environment where we took sounds away. You look at the scene and see explosions going off, but you don't hear any of them. Because in that particular scene we're going into the aural consciousness of a character called Roach, who is a human bat. The way he hears the war, when he sets out to kill "Charlie" -- and he echo-locates Charlie -- he doesn't hear anything except Charlie. The goal was to get audiences into the place where they hear only what Roach hears.

I worked on the napalm sound for a day in the mix. It includes a real napalm drop we got from a recording the Swiss Army had made of it. We built on that. The trick is always to articulate it, not to have everything hit at once or else it turns into a ball of mush. You have to let the ear hear fragments of each thing so that the ear builds it together, rather than have the film build it for the audience.

Francis was depicting Vietnam as the rock 'n' roll war, which must have dictated part of what you did.

At one point in the film's evolution, there was much more Doors music. The funny thing was that wherever we put whatever piece of Doors music we had, it was as if we had Jim Morrison in the room looking at the images and coming up with words to describe them. It was too much. All of the classic Doors songs, when we put them up against the film, were doing exactly what you don't want music to do -- they were simply duplicating what you were seeing visually or commenting too exactly on it. So we shifted course. But I think "The End" becomes even more powerful because of its placement at the beginning and at the end and nowhere in between. It would have been watered down if we'd followed the path we'd originally chosen.

Even the original music by Carmine and Francis Coppola recalls musique concrete -- music made of sound.

I was greatly influenced by musique concrete when I was, like, 10. I was completely mesmerized by the idea that you could make music out of sounds. So that's been a constant influence on all my work. But the films I'd done before "Apocalypse Now" had all been mono films ["American Graffiti," "The Conversation"]. Here was not just a stereo film but a whole new format. It was like jumping from a Stone Age tribe into, say, Wall Street. I was terrified of misusing the palette; I thought the worst thing to do would be to overuse it. I thought, instead, what you had to do was shrink the film down to mono at times, and let it be there quite a while. People without knowing it would think, "This is mono." And then, at that moment, you could make it a stereo film, and that would be impressive because now it was different.

And when people got used to that, you could make it quintaphonic or six-track -- at the right, the necessary moment. I wrote down a master chart of the scenes in the film with two timelines running alongside it. The results were like four-dimensional Einstein drawings. Sometimes there were single lines, and sometimes triple lines, and sometimes sextuple lines. When we were mixing the sound it showed us when the sound effects were mono and the music was in stereo, or when we should open the sound effects to stereo and close the music down to mono.

It kept us from losing perspective. It was the equivalent of what mural-makers do by breaking a huge mural up into a grid pattern. You only work on one part of the grid at a time. But because you have visualized the whole thing in advance and broken it down into pieces, you know what to do when you're working on any one piece. When I think about it, my unique contribution to the film was this concept of "sound design." It was the working-out of the mural grid that underlay the structure of the film, which was being developed with a dimensionality that hadn't been attempted before.

Is it ironic that this film, which shows the impotence of our technology against the spirit of the North Vietnamese, used such advanced technology to convey its message?

The relationship between the human spirit and technology is not a simple equation. It's got many dimensions to it, too. Part of the lesson of the film is that war has a seductive power. There's that quote from General Lee, which goes, "It is a good thing war is so terrible. Otherwise, men would love it too much." People gravitate to the power that any kind of technology gives you -- the power of a sword, the power of a machine gun, the power of a napalm drop or the power of an atom bomb.

People like that power. They like the flash of fire and the sensory recoil that goes with it. They like the smell of it. You have to put that alongside the negative aspects of war. But you have to remember that quote from Lee. Why do we do this? We do it for all of the usual reasons of acquisition and influence. But we also do it because of the seductiveness of it. The technology that we marshaled to make this film allows the audience to participate in the seductiveness of it. If the film had less powerful sound and less powerful visuals, that wouldn't have been possible.

Shares