During the three-plus hours I sat in the dark watching Paul Thomas Anderson's ensemble epic "Magnolia," I found myself wanting something I'd never wanted before. More Tom Cruise. As a white, middle-class American moviegoer who went to high school during the Reagan years and subscribes to more than one cable film channel, I've seen every film Tom Cruise ever made, some many more than once, without even trying. Like a Tom Petty or a Jim Lehrer, Cruise falls into that category of competent if ubiquitous public figures who have never won my love or hate and therefore never truly caught my eye. Except for his memorably baroque turn as Lestat in "Interview with the Vampire," which I, like the rest of the country, blame mostly on his curdled blond hair. But somehow, Cruise's work in "Magnolia," as male prowess guru Frank T.J. Mackey, so seized my curiosity that I walked straight out of the theater to go rent his 1983 film "Risky Business." Has he always been that -- whatever he is?

Tom Cruise is a mystery in plain sight. If one sets out to explain his appeal, all the normal movie-star reasons melt away. For starters, his looks. Cruise has never been a breathtaking beauty. The shock of "Risky Business," especially if your head's full of the dreamy teens currently steaming up the WB, is how ordinary Cruise looks. He's a regular, awkward kid, to the extent that I doubt he'd be cast in the lead now, what with pretty boy Ryan Philippe's head shots on a casting director's desk.

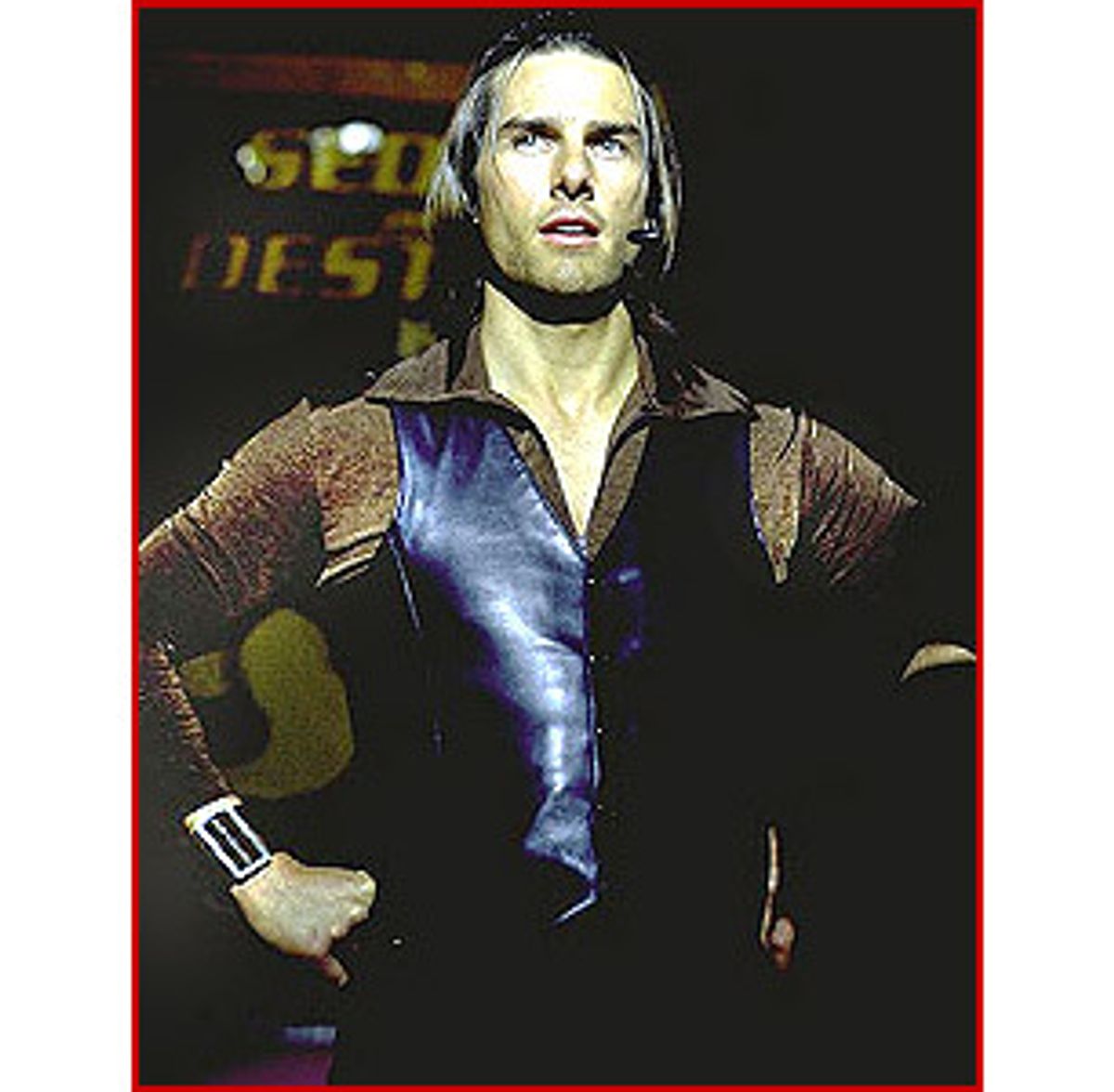

Cruise's face is too angular to be sensual. Whoever said that there are no straight lines in nature never bought a ticket to "The Firm." His face reminds me more of a math problem than a love poem, the nose and chin right out of high school geometry, hard vectors of flesh. Picasso might have liked to paint him, though it would have been too easy -- turning breasts and lips into rectangles is more of a challenge than making a box like Cruise boxier. Even his hair is drawn on with a ruler. Check out his short and sporty coif in "Mission: Impossible"; every individual strand is a line parallel to the Y axis. Which might explain a little of the "Magnolia" draw. Cruise's longer locks in that picture do make his face look a little softer, or as soft as it's possible for a man to look while he's swaggering around a stage inciting other men to date rape by proclaiming, "Respect the cock!"

I'd never given Tom Cruise's cock much thought before. I'd thought about the members of his contemporaries Nicolas Cage and Johnny Depp and, as long as we're on the subject, Steve Martin. But if you'd asked me to draw a nude Tom Cruise before seeing the bulge protruding out of his white underwear as he strips in "Magnolia," I probably would have given him the smooth anatomy of a Ken doll. Of course, where Tom Cruise sticks his privates is the speculation of the is-he-or-isn't-he homosexuality rumors that pervade his persona, but I never gave Cruise's sexuality much truck one way or the other. Because, watching his movies over the past couple of weeks, I am constantly surprised when Cruise is in the same room with another person, much less the same bed.

He strikes me as utterly, quintessentially, fundamentally alone. Of course Stanley Kubrick wanted Cruise to play the doctor in his "Eyes Wide Shut." Much of the movie requires the doctor to walk the streets of New York by himself at night, and when a director needs an alone-in-a-crowd, he calls Tom Cruise. The running gag about his title character in "Jerry Maguire" was that Jerry hated to be alone, but he also couldn't connect with anyone. In that sense, "Jerry Maguire" is the perfect fable of America's relationship with Tom Cruise. Basically, we think he's a stuck-up phony and we want to see him hit bottom, have his love interest notice for once that he isn't paying any attention to her and then we want to see him humanized, i.e., cry.

Cruise's two Oscar nominations -- for "Jerry Maguire" and "Born on the Fourth of July" -- display the public's deep desire to see Cruise put through a wringer. We want him to get his legs cut off ("July") and we want to see him lose for a while to the even slicker, if that's possible, Jay Mohr ("Maguire") because we want to punish him. Because I think the only reason that seemingly every man, woman and child in America goes to see his movies is not that he blinds us with beauty or talent or emotion. We can't take our eyes off him because he makes us a little nervous. Not too nervous -- that's why we invented Dennis Hopper. Cruise makes us stealth nervous, just jittery enough to keep us awake.

Watch Barry Levinson's "Rain Man" again and I guarantee you that the discomfort of Dustin Hoffman's shticky autism does not compare to the heebie-jeebies of Cruise's performance. Hoffman can dodder on about missing "Jeopardy" every 13 seconds and he's fresh air, but Cruise, closed off and angry, is a twitch fest. When Hoffman's Raymond throws a fit as Cruise tries to give him a hug, the viewer more than understands. While autism is the most natural thing in the world, an embrace from Cruise defies the laws of nature.

When the cute little kid in "Jerry Maguire" gave Cruise a hug, my first reaction was parental. I wanted to grab the child away, scolding, "We don't do that. We don't touch burning stoves, strangers' candy, and we do not touch Tom Cruise." Because Cruise is not, as the French say, good in his skin. Even in his most flawless, most affable performance, as Lt. Daniel Kaffee in "A Few Good Men," Cruise seems most comfortable on the softball field, having conversations with Demi Moore through a fence. Because Tom Cruise is the most talented actor of all time at keeping his distance.

Like most screen icons, Tom Cruise is not of us. Us, with our faces lumped together out of concentric circles versus his straight-edge mug. Us with our nerves and fears and him with his lieutenant-lawyer cockiness. Him with his choreographed cocktails and us dripping gin on our carpets as olives splash on the floor. But that's where Tom Cruise stops -- better than. There's no further inspiration to be gained. Like every time I see "To Kill a Mockingbird," I take one look at Gregory Peck's Atticus Finch and resolve to become more dignified. Even seeing Rene Russo in the remake of "The Thomas Crown Affair" made me vow to dress better, which, if not a moral for our times, is at least some little something. Cruise's best line in "Magnolia" comes when his character is asked by the reporter interviewing him why he has stopped talking. "I'm quietly judging you," he seethes, and that might be just what we're afraid of when it comes to Tom Cruise.

The mark of a great performance is that it obliterates distance, gets under our skin. It's simply harder for an icon to do that. But possible. "Magnolia" is the first time Cruise even comes close. It is far and away his most physical performance, if only because I'd never previously heard him breathe. About half of Cruise's screen time is taken up with Mackey's rooster struts -- again, alone -- across a darkened stage. His entrance, an amusing backlit pose to the strains of "Thus Spoke Zarathustra," isn't his only Elvis move. His debauched bumps and grinds as he speaks, fucking the air, punctuate his hilarious pigspeak with a new earthiness. He has never seemed more human -- which is to say funnier, more vulnerable -- than playing a man without the self-awareness to know that barking the words, "You are gonna give me that cherry pie, sweet mama baby!" might make him come off dopey, pathetic and sad.

We've never seen Cruise this lewd, and thus we've never really seen him get his hands dirty, dirty with the dopiness of desire. As my upstanding mother said when she called last night to tell me why she'd walked out of "that horrible, horrible 'Magnolia'" and wanted me to explain what's wrong with movies today, she sighed, "I'll never be able to look at Tom Cruise again."

I didn't have the heart to tell her that I feel like I've seen him for the first time.

Shares