A tall woman in a power suit

walks onstage at George Coates Performance Works, carrying

a shopping bag and a pair of chopsticks. She asks a butch dyke named Bongi

Perez if she's seen a "little yellow turdlet" she's misplaced.

"What do you

want it for?" asks Bongi. The power-suited woman says she wants it for

dinner. "Everyone knows that men have so much respect for women

who are good at lapping up shit," she explains.

Then they break into a camp parody of "Surfin' Bird" ("Turd, turd, turd is the

word") and Perez goes on to make snippy comments to the power-

suited woman for about an hour. It ends with a woman in a fur coat

strangling her obnoxious son to death. All of this is filtered through a fuzzy,

glitchy P.A. system, under the vaulted ceilings of what used to be a

Methodist cathedral, near City Hall.

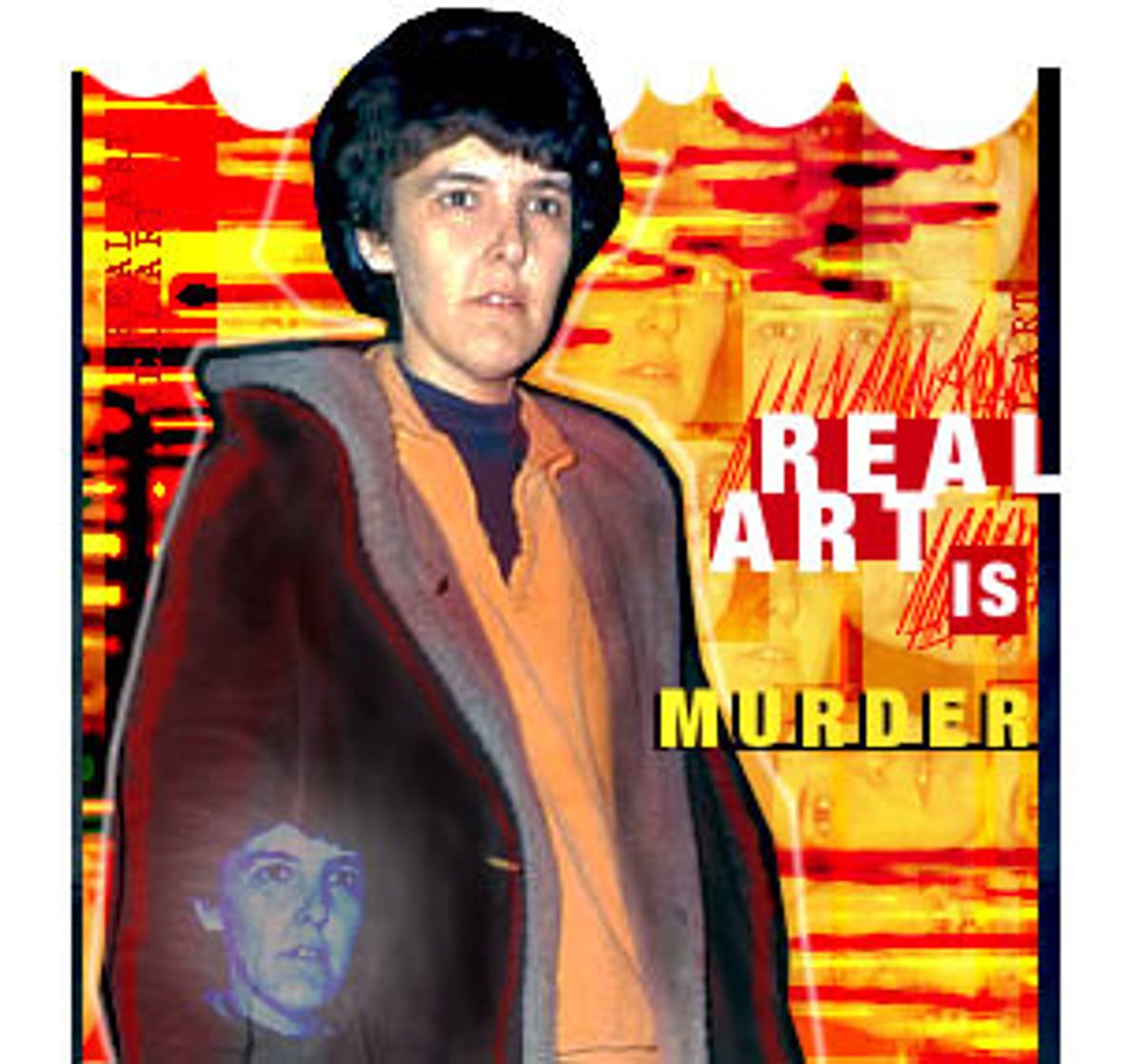

Scandalized yet? What if you learned the play was called "Up Your Ass,"

that it was written by Valerie Solanas, the woman who shot Andy Warhol, and that it was

being staged with several thousand of your tax dollars? Well, relax. It's not

being staged with anyone's tax dollars. George Coates applied to the

National Endowment for the Arts for funding of a less scandalous project, an Arthur

Miller play about censorship. With help from private funders, he's mounting

the two shows together, on alternating evenings, to make a point about

currents of "repression" in the United States.

Coates is a heavyset old radical with flowing white hair, a

scruffy beard and blue eyes set in pouchy sockets. He walks with a limp and

uses Cold War language to discuss pressures on the endowment. Ever since

a handful of right-wing activist groups and some Republican congressmen

waged a campaign to eliminate the NEA in the early '90s, there has been a

standards-of-decency clause in the endowment's charter, intended to keep

the most offensive works of art off the public payroll. (Andres Serrano's

"Piss Christ," a photograph of a crucifix suspended in urine, famously

outraged some Christian groups.)

Coates says it'll take a "Prague Spring" to lift the decency clause, and

describes the current endowment budget as equal to "about 2 inches on a

Trident submarine." He's a partisan in the culture wars partly because of his

hippie temperament but also because the sort of work he does --

experimental theater -- hemorrhages money and needs grant support to stay

alive. "In the past," he says, "I could have gotten an NEA grant for 'Up Your

Ass' -- even during the Reagan administration."

He picked Miller's play, "The Archbishop's Ceiling," for a reason. It's a Cold

War-era story, set in Russia, about a group of writers who meet in a house

that once belonged to an archbishop. When they learn that the florid old

ceiling is probably bugged by the Kremlin, the paranoid writers

change their behavior for the microphones in a way that, for Coates,

expresses the effects of the NEA's decency clause. "I can't apply for 'Up

Your Ass,'" he says, "but if I do it as a double-book, that is, two shows

together, and one of them is a show that is censored today and another is

about censorship in another culture, do they inform each other in some way?

That's the examination that's going on now."

In 1996, the whole NEA budget was reduced by 40 percent, from $162

million to the current level of about $98 million. Roughly a thousand arts

organizations lost their grants completely; others took substantial cuts.

Congress also ordered the endowment to stop funding individual artists or

organizations and start funding specific projects, so there would be no

confusion about where the money was going. (Pat Buchanan fueled the "Piss

Christ" controversy by holding up the picture during the 1992 presidential

campaign and declaring that Bob Dole had voted for the budget that funded

Serrano. Of course, Dole had never heard of Serrano. The money went in a

block to a larger exhibition.) The changes were seen as a victory by the

Republicans -- conservative columnist George Will called the decency clause "a sop to, and a

(successful) attempt to deflect, those who wanted to abolish the NEA" -- and

essentially saved the endowment's skin.

Coates calls it censorship. He thinks the NEA crossed a sacred line when it

accepted a mandate on content, as opposed to simple craftsmanship. "When

you go into a contract with a plumber, you've got to get plumbers that know

what they're doing," he says. "But to take the contract away from them

because two of the plumbers are surrealists on the side -- that's a content

restriction. That's really a form of oppression leveled at a certain class."

Opponents of the NEA, of course, disagree. The American Family Association, a

conservative Christian group based in Mississippi, lobbied Congress in the

years before 1996 to stop funding the endowment altogether. The AFA declined to

be interviewed for this article. ("What is Salon? Is it a homosexual

magazine?" asked spokesman Allen Wildmon.) But the AFA does have a

Web site with articles stating its position: "Contrary to the argument of

some," one article reads, "AFA does not believe that the elimination of the

NEA is censorship. Great art has existed for thousands of years without

governments funding it. AFA believes that artists should be free to produce

what they want -- but that taxpayers should not be forced to pay for it."

That reasoning is what led the Supreme Court to uphold the decency clause

in 1998. Performance artist Karen Finley argued, in Finley vs. NEA, that the

clause was a First Amendment violation. Federally funded artists, she

asserted, have a constitutional right not to be judged on the content

of their projects. Justice Antonin Scalia and the majority disagreed, ruling that the

government can do as it pleases with its money.

That seems logical enough. But a larger question was never addressed

by the court, since it had nothing to do with the lawsuit: Is this any

way to run a national arts fund?

John O'Brien heads the Dalkey Archive Press, a small

publishing house in Normal, Ill., that's typical of the sort of arts organization

that didn't exist in America before the NEA was founded in 1965. Dalkey

Archive books are literate, obscure and generally unfloatable in the

marketplace. They rely on NEA grants, and O'Brien thinks the funding

should be an all-or-nothing proposition. "Either you believe that there is a

proper role in the government to support the cultural health of the country,

as every civilized country does, and usually to a far greater degree than the

United States has ever done," he says, "or you believe that the government

should have no role in this, that it should be left to the marketplace, or it

should be left to individual donors or foundations."

O'Brien opposes the decency clause but doesn't think Finley made a

strong case that it constitutes censorship. "I don't know about a legal

argument," he says. "But I would say that it's an almost indispensable

function of government to recognize that art has a profound effect upon what

happens in this country. There's an argument I've made for years, and I think

I'm absolutely right about it, that this country was not aware of race

problems until those race problems appeared in literary form. I really

attribute the civil rights movement, for instance, to the fact that

imaginatively we could grasp the issue of race in this country through such

writers as Jean Toomer and Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison.

"Does art have that kind of impact, of making us aware of who we are as a

people, and is that valuable for us to know? I suppose at that point it

becomes the old Socratic value of 'know yourself.' Well, do we want to? The

great fear in any society is of artists, because they're the ones who give us

conceptions of what's going on and what will be going on."

As for Solanas' "Up Your Ass," it's a deliberately outrageous diatribe dealing

with sex roles in America. Coates thinks it usefully violates the taboo against

violent women. He started looking for the script when he saw Mary Harron's

1996 film "I Shot Andy

Warhol," which recounted Solanas' obsession with Warhol and his

Factory. Solanas has a cult following because of a satirical book she wrote in

the '60s called the "SCUM Manifesto" (SCUM stands for the "Society for

Cutting Up Men"). In 1965 she wrote "Up Your Ass" and asked Warhol to

produce it; he not only turned her down but, with typical Warhol

carelessness, managed to lose her script. Three years later, paranoid and

delusional, Solanas stalked him and shot him in the chest. Although he

survived the shooting, Warhol never fully recovered. When he died in 1987,

complications from the wounds he had suffered 19 years earlier were partly

to blame. By that time Solanas was all but forgotten. She died destitute in

1988 -- in San Francisco, not far from Coates' theater.

"I thought it was a worthy project to examine what she wrote before all

that," says Coates. "Before her break with reality, before her assassination

attempt and before the "SCUM Manifesto" even, there was a time when she

was on her game and writing comedy more like Lenny Bruce would write

than like a mad stalker. So is there any value in examining that piece? Well,

we'll find out by doing it. Let's apply to our funders."

Someone at the Warhol estate found the script a few years ago at the bottom

of a crate of lighting equipment, and it needs to be said that this brief, rude,

battle-of-the-sexes farce, which led to an attempted murder and took 30-odd

years to premiere, is ... well, slim. Performing it straight through takes about

40 minutes, but the karaoke-style songs Coates has added (like "Turd Is the

Word") fatten the show and occasionally even improve it. Some routines are

hilarious -- for example, a lesson in homemaking given by an old German teacher in

cat's-eye glasses, with toilet paper stuck to her shoe -- but most of it is just a

scurrilous blast of anger, not a brilliant exploration of maenadism in

America.

Whether "Up Your Ass" works or not, Coates believes he should be free to

fund the show with NEA dollars. "There will always be bombs," he says.

"It's like you have to shoot 3 feet of film to get 1 foot of movie. That's

part of the process. When the Pentagon drops a bomb on the Chinese

Embassy, we don't say, 'Oh, we gotta defund the Pentagon.'"

The reason a decency clause in the NEA charter matters is that the

endowment has enormous influence -- probably more than it wants -- in the

world of nonprofit art. Its grants are small but official gestures of approval;

private and local funding outfits tend to follow the NEA's lead. Winning or

losing a grant can mean winning or losing a bouquet of other money, and for

groups that rely from year to year on the endowment, one rejection can be

disastrous. Coates has been careful not to use any of his federal money to

stage "Up Your Ass," but he worries that the pall cast by the decency

clause on theaters, museums, orchestras and orchid presses across the

country will have an invisibly repressive effect. "In fact, we need more for 'Archbishop' than

we're getting from the NEA," he says.

O'Brien at Dalkey Archive agrees. "You never turn down a book because it

won't receive NEA funding," he says. "But it begins, in some very insidious

ways, to make you second-guess certain things. And if that happens in

publishing, they've won. As soon as you start thinking, 'Oh, God, what is the

NEA going to think?' and 'Are we going to hurt the NEA?' they've won."

Shares