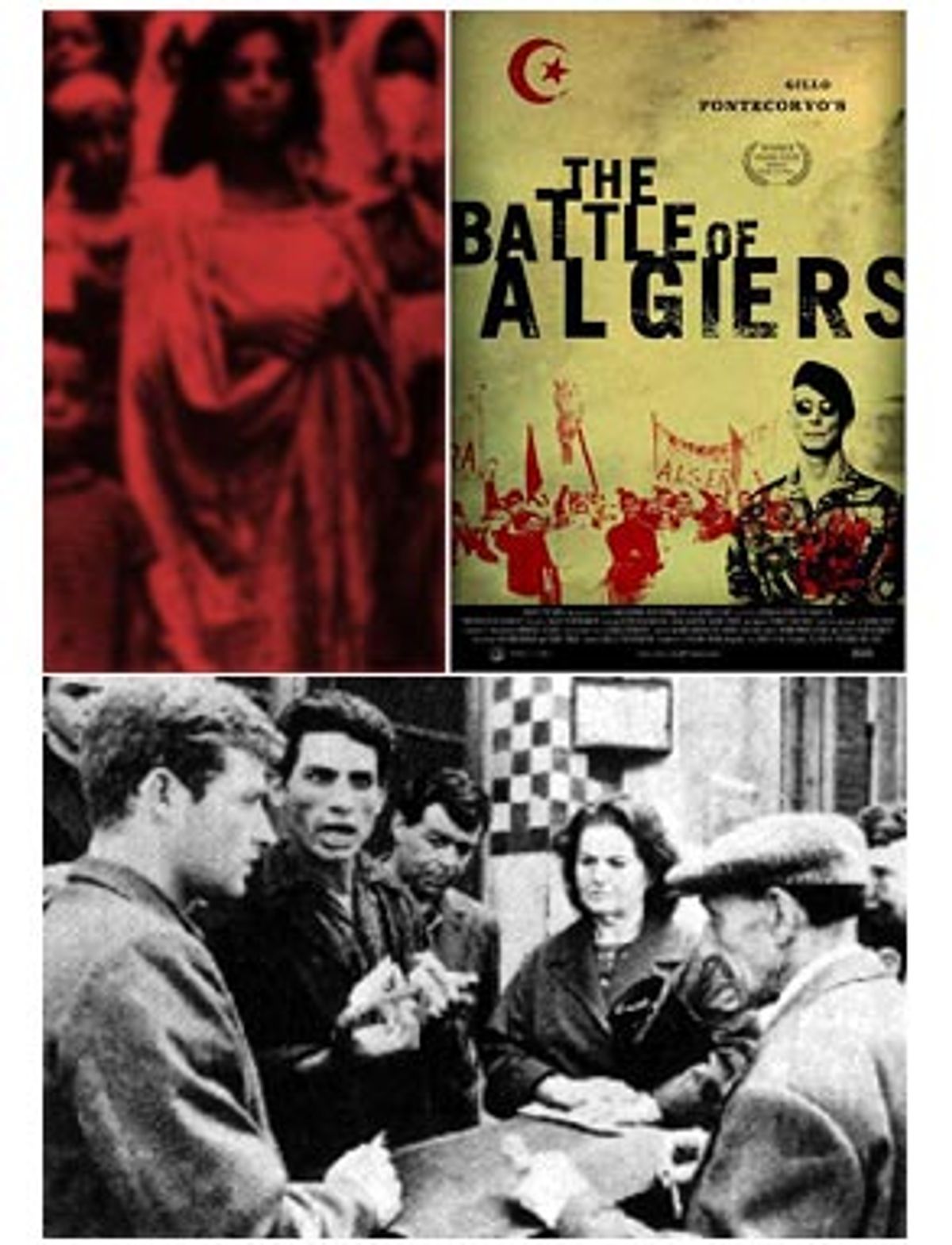

Fifty years ago, Saadi Yacef was an Algerian revolutionary fighting France for his country's independence, planting bombs to kill French occupiers, including civilians, and hiding in the raw sewage of Turkish toilets when the authorities came looking for him. The French government went so far as to ban "The Battle of Algiers" -- a movie Yacef produced and starred in, based on a book he wrote about the insurrection -- soon after the film's 1965 release, due to its subversive nature.

How times have changed. Today, Yacef is an Algerian senator. "The Battle of Algiers" -- which has long been a cult classic, a favorite of professors of postcolonialism and your typical revolutionary types -- is recommended viewing for officials at the Pentagon, which held a private screening of the film in August. Officials described it as an illustration of "how to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas." As former U.S. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski told an audience in October, "If you want to understand what's happening right now in Iraq, I recommend 'The Battle of Algiers.'"

Because of the film's newfound relevance, its distributor, Rialto Pictures, is rereleasing the movie Friday at theaters in New York, Washington, Chicago and Los Angeles. Yacef now has a French publicist who guides eager members of the press under the gilded ceilings and gleaming chandeliers to his posh digs at New York's Plaza Hotel. At 75, Yacef doesn't look much different from the handsome, charismatic figure preserved in the grainy black and white film. It's tough to reconcile the fact that this man, dressed in a black sports coat and turtleneck, armed with a warm smile and quick laugh, once helped kill French civilians on a daily basis.

While the film was not a documentary, Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo didn't use any professional actors to portray the Algerian rebels; instead he chose to use average Algerians, for whom the memory of winning independence, which finally happened in 1962, was still fresh and poignant. Many of the scenes were shot in the exact locations in which the original historical event occurred. The cinéma vérité style of Pontecorvo's handheld camera makes it feel like you're watching history. But it has been most widely praised for successfully capturing the complex moral dilemmas faced by both the occupiers and the occupied, who feel driven to terrorist acts. As critic Pauline Kael wrote, "'The Battle of Algiers' is probably the only film that has ever made middle-class audiences believe in the necessity of bombing innocent people."

So what does Yacef think of the terrorist tactics by Islamist militants today? He condemned much -- in particular the Sept. 11 attacks -- as blind hatred without a just cause. Yet on the subject of the attacks against American soldiers in Iraq, he seemed to waiver. When asked if the cause of Iraqi insurgents was just, Yacef at first said yes, then seemed to hesitate. He stated that he himself opposed Saddam, but complained that the process of transforming Iraq into a democracy ruled by Iraqis was taking too long, keeping the country plunged in chaos. In the end, Yacef's sympathies seem to more naturally align with the insurgent force.

Salon spoke to Yacef, with the help of a translator, about how the film and his experiences are relevant to the U.S. involvement in Iraq today.

When you helped make this film, did you think "The Battle of Algiers" would be still be considered relevant 40 years later?

I never imagined the film would have this kind of resiliency and popularity 40 years later. When I made the film, I was sure that it would be a classic and last for a very, very long time. But now, 40 years later, for example with the Pentagon, the film has another aspect: It brings to light our war in Algeria with the war -- and I'm going to call it a war -- in Iraq. And it enables us to look at the two situations and see, are there things we can draw from the Algerian experience, mistakes or errors that were made.

What kinds of lessons do you think the United States should learn from the film?

It's important to note that the war that took place in Algeria is not the same as what took place in Iraq. The reasons are different -- although the real reason [for the U.S. occupation], I don't know what it is. But there are lessons to be learned. For example, the Americans shouldn't stay there for a long time. Because what will happen is, from a very small, small resistance, it will spread over time like an oil spill spreads, further and further. What will happen is that the Iraqis, the different groups, the Shiites, the Kurds, will end up uniting and developing a nationalistic attitude in order to get rid of the U.S., the outsider.

In Iraq now, the GI's and the marines are very brave soldiers who have been trained to fight a real war as real soldiers -- and now they've become police. The style of fighting is very different. This is what happened with us, in our country, with the French. General Jacques Massau -- who is Colonel Mathieu in the movie -- he commanded a very large army that was sent to the capital city, Algiers. He was in effect a policeman, and his army became an army of police. He was granted all special powers. They gradually engaged in activities like torture and murder, and these were things that over time created a feeling of malaise that led to the downfall of the Fourth Republic. Among the soldiers who were based there, there were many who were deserters, many who committed suicide. A great deal of the families of these soldiers were receiving letters at home that their sons had been killed there ... If the United States stays in Iraq, this definitely may be what happens.

But at the same time, if the Americans leave, that would be a very dramatic thing for the Iraqi people. Then, as a civil war, the Iraqis would begin to kill each other. There would be thousands of deaths that way. My opinion is based on having fought for many years against 400,000 European occupiers in the country and 80,000 soldiers. I can tell you right now that if the army were to come into this room right now, I would be able to hide myself, and they wouldn't find me. [Laughs.]

It isn't often that someone who's a part of history gets to reenact that historical event in film. How is it for you to watch the movie now?

When I see the film, I fall in love with it again -- like a girl.

I put myself into the skin of an actor. It was a difference in acting in reality to acting in the film. But the director was there, and he made me act the way he wanted me to act. What I can assure you is that everything that took place in the film is something real that took place. And what I tried to insist on is that we use the same locales in the film. I'm in the film, but it was not my original intention to star in the film. But it was the director who asked me to be in the film. And one reason I agreed was because I wanted to make sure that no errors were committed.

I killed people. I did it for my country -- in real life. Now, I can't even kill a chicken. I'm another man.

At a blockade, you would come to a stop, and they would check you with metal detectors. So a bomb that was 10 or 15 kilograms, I was able to transform into a plastic bomb that was the size of a cigarette package, with a small battery. We would put it into a metal birdcage, and take the cages with us. When you passed through the checkpoints, they would see that the birdcage was made out of metal, and they let you by, with the bomb underneath in the cage. [Laughs.] I'm not going to tell you these things.

The success of the film is based on the fact that it shows the reality, and the reason why the Pentagon is interested in looking at this film is to see how did the French react, how did the French get out of Algeria. But the truth is that the French themselves never learned the lesson that can be drawn. For example, you have the French in Madagascar in '47, then in Vietnam, in Morocco, in Tunisia. They never learned these lessons. Each time, it was like something new.

What about in the Arab world -- now most of the colonial powers are gone, but there are still many dictatorships. Do you think things have really changed?

Not totally. There were countries that were almost 90 percent illiterate, meaning 10 or 15 percent were literate. It was this small percentage of the population, the literate population, who blew up the bombs. We were the people who were able to channel the rest of the population in that direction. In the case of all revolutions, there's an evolution and a change in the mentality of some of the population. That can also lead to a conflict within the country, within the peoples within the country.

We can use France as an example. There was this sublime revolution of 1789 -- liberty, fraternity and equality. The precursors of this revolution are the people who have prepared this revolution, for example Voltaire, Robespierre. In the end, these were all people who were decapitated by the revolution that they had created. I'm very happy to have my head on my shoulders -- with a wound, of course. [He points to his right side.]

You mentioned your participation in bombing civilians. Those kinds of tactics have really influenced the Middle East. Do you think this is leading the Arab world in a good direction?

In some cases, it is useful. For example, in Algiers alone, there were 400,000 French civilians -- and they had placed bombs long before the FNL detonated even one bomb. The colonists didn't want Algeria to be independent. They had their own infrastructure in the country, almost like apartheid. They provoked us, and these colonialists -- against the policy of the government in France -- insisted that Algerians who had been arrested be executed. These colonial vigilantes would describe themselves as paratroopers. In military uniform, they would enter into houses and slit the throats of children. These were our enemies, more than the actual military. We offered them the chance to be part of one country, and people like Albert Camus were brought in to promote this idea, which the French colonialists refused to consider.

What took place was horrible. These were atrocities, but it was war -- and attacks take place against civilians and against the military. What's sad is that there were babies, children, young people, without arms and legs -- they were cut off. This is the one thing that really saddens me. As for the rest, I consider myself a soldier without uniform.

I tried to make the film a very balanced film. It's not like when the French make a film about the Germans, because when the French make a film about the Germans, the Germans are always the bad ones. For example, when the woman goes to place the bomb, you see the French baby eating the ice cream cone. I did this deliberately. I could have cut it, but I didn't. I wanted to show violence on both sides, in different forms.

Now, for the Arab population, there's really no reason for them to use terrorism. The real terrorism would be to go into the schools and begin to educate people and begin to bring them to a level of more scientific knowledge. You fight for something like this. They want to really apply a religion that's different from the religion of Muhammad. For example, in Algeria in certain places, if you're sitting in a chair and you're eating with a fork, what you're doing is considered to be against Islam. You're the enemy of Islam. Because the Prophet Muhammad didn't eat with a fork -- you have to eat with your fingers! And now there's terrorism in Algeria -- a little -- it's been going on for about 10 years. And children of a few years old are being killed. Why? Why? For what reason? They are free, in a country that's free. We shouldn't have pity for these kinds of people, because these people are really destroyers. What they're doing is not to defend a cause or the truth. If it was for a just cause, then yes. But just to go out and kill, to bring down two towers in New York, what's the result?

In Iraq, are the bombings of the American soldiers just?

Yes. [Hesitates.] I would've given a lot of money and done a lot to get rid of Saddam. But where is the democracy? Arabs have never been democratic, only in a few countries.

[The allotted interview time ends, and Yacef and his entourage prepare to leave.]

But is that a problem of the Arabs or a problem of the West?

It's a problem of the whole world. You have to learn to be democratic, developed over time. Somebody can't just come over to you and say, "Now you have to be democratic." It must be learned.

Shares