Quiet, superb afternoons of snow on Tremper Mountain, the light quitting early, the candles go up by 4 p.m. In morning, I squat to defecate in a ravine downhill, and then the ritual of waking-by-gun: sometimes the boy-like .22, which makes little pops and might make a fox laugh if I brandished it; or the gruesome AK, a semi-automatic Romanian thing, an assault rifle, rude, very loud, bought on a whim (cheap), designed, at bottom, to further insurrections and slaughter villagers. Then there's the hunting rifle, a Winchester lever-action, famed exquisite straight shot of the Old West.

Most gun nuts are also hunters. I count myself in neither camp, but I can converse easily with both, as long as no mendacious arguments about "constitutional privilege" come up. To the Second Amendment zealots I always say, "Guns are merely an extension of the fist, and their ultimate purpose is not defense, but the increase of power. That's why they're so much fun."

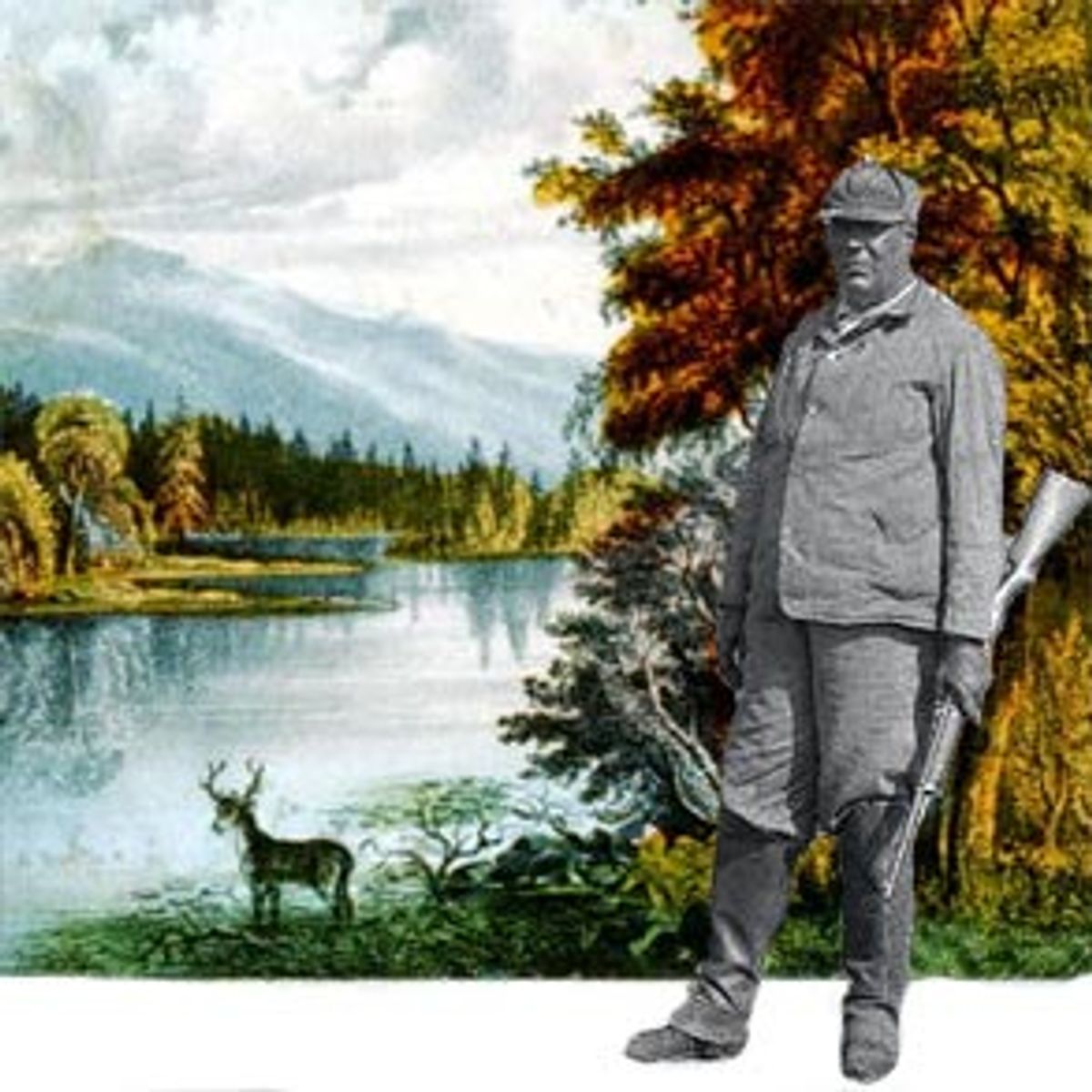

So the hunters are out for the three-week deer season here in the Catskills, 100 miles north of New York City, and the urge among all good men is to grab fatigues, rifle and scope. Bag a three-point buck in the haunted woods. Often in the blue mornings, when I'm shooting, I hear the echo of my reports, and others, from across the valley, and hear the wash of silence over the disorder of human sounds. There is a part of me that turns away in shame; a feeling of obsceneness, mixed with the adrenal rush of the crack and the recoil and the shattered blocks of cut wood. I used to fire into a tall oak near the cabin, but was ashamed too at the damaged bark. In this island of forest, where the major highways run only 20 and 30 miles away, most of the trees are second growth, the generation before logged to exhaustion for tanneries and mills 100 years ago.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The kill: a 30.30 Winchester is a cannon, it pierces flesh straight and fast. One shoots without emotion, extending that big fiery fist, and just as in any fight, the drawing of blood happens as if one were watching from another room, wholly disembodied.

The deer, shocked that his life runs from him, stands for an excruciating four or five seconds. He stumbles like a drunk, settles down as if to kneel, tumbles, twitches. The death-act, like Bugs Bunny's, is full of urks and ools and blurghs, a holding up of fingers, a tumble-down drowning in air. The death shock resounds in the forest by the silence of his fall, reminding the hunter that his life will not end as dramatically.

On the main road off my property, big buses and motorcycles move fast on the gully curves. Nearby, I once found the rotting summer-heated bodies of a mother deer and her child next to the river that runs along the road. It was an odd grave: the mother was well-eaten, the child freshly dead. I understood: the mother had been killed by a car or an out-of-season bullet, and was dumped here. The child watched from the forest, and like any child, later crept by her mother's side, not knowing what to do, too young to forage. She starved to death waiting for her mother to wake up. Mother with maggots, the half-yearling with an oily coat, drawing flies.

Chance meetings: the porcupine I spent 10 minutes talking to on Giant Ledge Mountain. The mad-eyed raccoon who stood peering into the flashlight at midnight. Tracks of bobcat in the snow, with their overlarge splayed feet that resemble those of the long-vanished Catskill panther. Hiking at night, a cherished vision of a big cat: Seventy feet down the path the figure lay prone, then leapt and was gone, and I aimed my lamp into the underbrush.

The remembrance of an animal encounter is always romantic, the actuality always the sum of our fear and their fear. In retrospect, we'd like to think there was some sort of contact, and that there was a mutual desire for association, that the animal actually turned and said, "Yes, yes, I've noticed you as well, poor thing, and it was really exciting."

We are strangers on the mountain; they have lived here for ten hundred years and much longer. They know a lot more than we do about this place, and therefore we go armed; traps of poison and trickery keep them out of our gardens. They can smell us in a good wind, we hear them, barely, in imagined sounds, and imagine them much larger than they are. In the cabin in August, a giant clears his nose in the hemlocks up the hill. My girlfriend wakes up -- "Hear that! Jesus!" -- I load the Winchester and wait by the door, expecting a bear come for meat-leavings. This happens in the Catskills: A group of hunters abed once awoke in their lodge to a bear rifling food. The bear broke the door open, had his fill and lumbered out, while the hunters hid under the covers in long-johns.

Later, I describe the fearsome night-snort to a local: "That was no bear, that was a deer, a big deer, clearing his throat, he probably smelled the smoke from your cabin and didn't like what he smelled."

Ready to kill: to defend the smoke from my cabin.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

We like our forests Wordsworthian: green glades, waterfalls, orchard idylls. So our encounters with beast nature make us reach for guns in a kind of "Little House on the Prairie" pretense/reaction: the husband and father surrounded by wolves, the house in flames, Indians in the hedge brush counting scalps. We want the little taste of the frontier, too, the woodsman against nature, stalking the way his forefathers did for food, for the tribe, for grim survival.

When I was younger, hunting with my uncle, I tried to kill a deer with the Winchester. I scoped a buck at 300 feet in the clear leafless autumn. I waited for a long time, watching him through the sights. He pecked at pieces of grass, looking confused and dumb as deer often do. I hung on the trigger; my uncle told me to shoot, now. The creature noticed us, at last, and seemed curious about the two men aiming long poles his way.

But the living thing before me was before me: The fact of his realness was what stood out, and the fact that I could remove him from realness, and make him an idea, the fantasy of the kill, and make his head property on my wall. He was looking at the same dark flesh of trees and dusk, enjoyed, like me, stuffing his face in the same streams nearby.

You're hopeless, my uncle might have said, or thought, but he didn't say anything. This was no rite of passage, and we would not starve that night. It was a moment to decide how to approach the wilderness, and he understood.

Shares