I'm definitely not neutral when it comes to Ingmar Bergman, but the astonishing thing about "Saraband" is not that he's made another film at age 86 -- it's how lean, sharp and vigorous it is. There is nothing here of the fuzzy sentimentality that clouded the lenses of his contemporaries like Kurosawa, Truffaut and Fellini as they drew near the ends of their lives (or, for that matter, that has inflected some of Bergman's recent, mild-tempered work). Amid the over-stylized clutter of so much contemporary film, this movie's combination of naked, almost ruthless family drama, visual intensity and narrative economy feels like a blast of cold Scandinavian air from a suddenly open window. If this doesn't rank among Bergman's very best works, that's an impossibly high standard; "Saraband" still strikes me, on first viewing, as the best-crafted, least self-indulgent film I've seen in years.

This is meant to be Bergman's last film, but as actress Liv Ullmann quipped at a press conference after the New York Film Festival screening I attended, he has said that before. Several times, in fact. ("Saraband" premieres in the festival on Friday.) "Fanny and Alexander," the sweeping family chronicle that summarized much of his accomplishment, was Bergman's first farewell. That was 22 years ago. Like any artist still in possession of his faculties, Bergman has been unable to stop working, but without quite reneging on his promise. Since the mid-1980s he has directed plays for the Royal Dramatic Theatre of Stockholm, written novels and memoirs, and even authored screenplays for other directors (including Bille August and Ullmann, his longtime collaborator). He announced his retirement from the theater in 1995, but hasn't stuck to that either -- I saw his production of Ibsen's "Ghosts" last year at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Over the years, he has also directed several modestly scaled television productions that began to seem, more and more, like new Ingmar Bergman films.

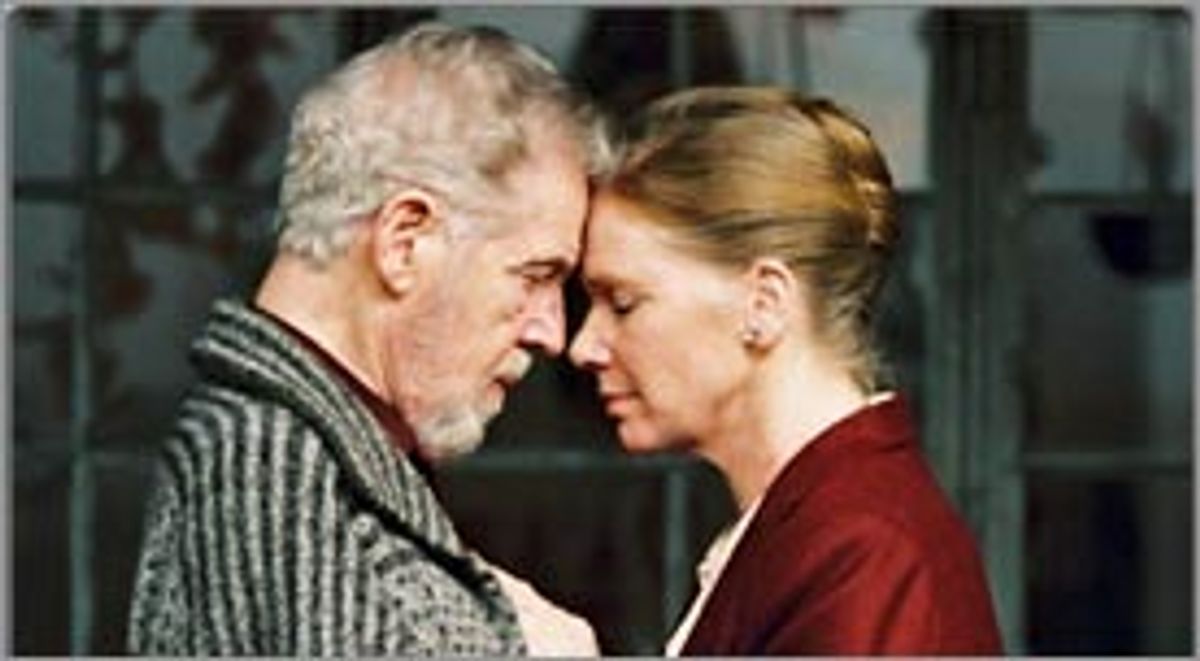

Now comes "Saraband," which despite its fusty-sounding classical-music title is an intense emotional stew that reunites Johan (Erland Josephson) and Marianne (Ullmann), the feuding, neurotic couple from Bergman's 1973 "Scenes From a Marriage." Creaky, crotchety Johan is almost exactly the director's age, and Bergman himself was once married to Ullmann, so it may be tempting to read the story of this marriage and its aftermath as autobiography. Ullmann explicitly denies this, and as usual with works of art, it's probably more fruitful to assume that some act of psychological translation is occurring. Johan may reflect a certain aspect of Bergman's personality, but if so it's one he would like to ventilate or exorcise as much as possible.

When Marianne shows up at ex-husband Johan's inherited summer home -- longtime Bergman viewers will immediately recognize this house, or at least this kind of house, as an archetypal element in his work -- they haven't seen each other for 32 years. She's a Stockholm lawyer, drawing near retirement age, reasonably content, perhaps a little lonely. His conclusions about himself are different: "My life has been shit," he tells her, "a totally meaningless, idiotic life." Nope, we're nowhere near Golden Pond in this portrayal of old age.

Johan isn't likely to make such a confession to anyone else in his life, but he may have a point. He has completely lost touch with his two daughters from his marriage to Marianne, one of whom lives in Australia and the other of whom is confined to an institution with an unexplained illness. He and his middle-aged son Henrik (Börje Ahlstedt) -- from an earlier marriage, before Marianne -- view each other with undisguised hatred; their relationship consists mostly of a not-so-cold war over Karin (Julia Dufvenius), Henrik's beautiful 19-year-old daughter. A washed-up and impoverished music professor, Henrik clings a bit too closely to Karin, who is a promising cellist. He is tutoring her privately and refusing to let her leave home until she's ready (in his eyes) for a conservatory. With his inherited wealth, Johan has grander plans for Karin, involving an antique Italian instrument, a prestigious Russian conductor and an exclusive music school in Helsinki. What only Marianne, as an outsider in the household, can see is that neither man seems ultimately concerned with Karin's welfare and that both are haunted, at least figuratively if not literally, by the ghost of Karin's mother, the beautiful Anna.

I don't want to say too much about the role that Anna plays in "Saraband," but it's safe to describe this as another one of Bergman's ghost stories, even if the dead woman never appears in any literal, Hamlet's-father manner. ("Saraband" is dedicated to Bergman's wife Ingrid, who died in 1995.) Over 10 numbered scenes with these four characters in the summer house (along with a mysterious epilogue that features a fifth person), this tense little saraband -- which is in fact an erotic dance as well as a musical form -- plays out. His great leonine head carved like a glacier and his eyes still burning with skeptical ferocity, Josephson plays Johan as a man essentially unbowed by age but almost eaten out from inside by his self-disgust. Ahlstedt nearly matches him; Henrik is a big, huggable walrus in a dingy undershirt, uneasily pitched partway between sympathetic and pathological. He tolerates terrible abuse from his father for Karin's sake -- but when you realize that he and Karin sleep in the same bed, well, you'd be right to wonder about how healthy this whole situation is.

I imagine "Saraband" will be a gripping experience even for viewers new to Bergman, but there's no question that his fans will find in it countless echoes -- ripples may be a better word -- of his earlier work (even beyond the fact that this is a sequel of sorts). There are cuckoo clocks, doors that close without human agency, letters read by people to whom they're not addressed (with fateful consequences), suicide attempts played as very dark humor, Spartan country churches, a young girl who cannot communicate with her father and escapes into the forest. (I would enumerate the references, but they're almost too many to count.) This is also a story of an old man who knows that he has drawn very close to death, that it could come at any time. As Bergman viewers know, this is scarcely a new theme for him. If that awareness is more present for Bergman himself than ever before, it nonetheless does not dominate this film. For all the alleged darkness of his work, Bergman's movies are more about how to survive and even how to love than they are about death or despair, and "Saraband" is no exception.

Bergman has been working with high-definition digital video (DV) for the last few years, and those who have doubted that DV could ever deliver the depth and loveliness of celluloid now, I think, have their answer. The simplicity and precision of the camerawork, from the subtly alarming zoom-ins on a character's face to the elegant stillness of the two-character setups, is vintage Bergman. And some of the shots here -- Ullmann listening to a Bach organ work in one of those rural Lutheran churches Bergman cannot resist, Dufvenius and Ullmann laughing and drinking wine, burnished with an almost Renaissance glow -- are so beautiful you want to stop the movie and spend a day or two in them. If Bergman really is the first artist to make DV look great, there's nothing especially ironic in that. Despite his reputation as a creator of talky darkness, he's always had a painter's eye for composition -- and used the technology then available to break down the wall between narrative and experimental film in 1966, with "Persona."

Whether or not "Saraband" is the final work of his extraordinary career (and as long as he's still breathing, I remain unconvinced), Ingmar Bergman can never again be what he once was. From the late 1950s through the early '70s, one could speak of him, utterly without irony, as the most important filmmaker in the world, and maybe the most important artist, period. But the movie universe, along with the universe in general, has shifted on its axis since then. The art-house audience that made "Smiles of a Summer Night" and "The Seventh Seal" and "Persona" famous around the world was essentially an extension of the high-culture market of symphony halls, art museums and modernist drama, and has withered away. The new art-house audience has been nurtured instead on a pop-culture smorgasbord of music videos, '70s and '80s sitcoms, horror movies and mock-serious cartoons. It belongs to either the big, sweeping gesture or the arched eyebrow (or to both at once) -- to Scorsese and Tarantino, to Wes Anderson and the Coen brothers. Bergman's demanding and often painful dramas -- stemming, as they do, from Strindberg, Sartre and the A-bomb, from the 20th century's existential and spiritual crisis -- are now dreaded as much as respected.

But what goes around comes around, in movies as in anything else. Who would have predicted a generation ago that Luis Buñuel, the inscrutable surrealist and practical joker, would prove to be the defining influence on a new generation of European directors? Bergman's influence is not now a dominant strain, but you can still see it all over the place, in younger Scandinavians from Lars von Trier to Thomas Vinterberg to Christoffer Boe (the entire Dogme movement could be described as a method for making imitation Bergman films), in American Cheerios-realism like "In the Bedroom" and "You Can Count on Me," in the television universe of Alan Ball's "Six Feet Under" (perhaps the best and most vital example). There's no way to know what forms Bergman's legacy will take in the future and where it will lead. As with any really important artist, though, the real thing is inimitable. "Saraband" is here now, and it's prickly, electrical, alive.

Shares