The first thing you see when you walk into the installation "The Universe Within" is a dead Chinese man with very little skin. His hands are triumphantly on his hips, and he's made to revolve slowly on a turntable like a track and field trophy. A large rhombus of muscle is partially carved off his buttocks and peeled forward, and if you look closely at its edge you notice the familiar, pinkish marbling of a raw flank steak. And then you have an indescribable little epiphany: You realize that you're looking at this gentleman's actual flanks.

"The Universe Within," now at San Francisco's Nob Hill Masonic Center, is a traveling road show of 21 provocatively posed human bodies and a menagerie of organs, all embalmed by a process called "plastination," in which body fluids are replaced with liquid plastic. It hails from China and joins two other wildly successful touring exhibits: "Body Worlds" and "Body Worlds 2" (currently in Chicago and Cleveland, respectively). Those exhibits are promoted by plastination's inventor, Gunther von Hagens, and have grossed nearly $1 billion worldwide. They've also incited almost perpetual controversy, due in part to von Hagens' Barnum-esque eccentricities. (Most notoriously, after bullet holes were found in two of his specimens' heads, he was accused of, but never charged with, using the bodies of executed Chinese prisoners. Then in March, when the Body Worlds 2 exhibit was in Los Angeles, someone walked off with a 13-week-old plastinated fetus.)

But after "The Universe Within" debuted in San Francisco in March, it quietly went about its business for two full months before arousing suspicions from local government and scandalizing the citizens. Last week, San Francisco's ABC affiliate reported that the bodies were leaking a viscous combination of silicone and liquid human fat (signs of a "rush job," according to anonymous plastination experts cited by the news station). Moreover, the station reported, the corpses were not the property of the Medical University of Beijing, as initially claimed by one of the exhibit's promoters, an Austrian TV producer named Gerhard Perner. The university has never heard of Perner.

So whose bodies are they?

"Where the bodies came from in terms of donors, they don't tell us anything," a docent of the exhibit told the station's investigative team. "They tell us, 'Don't talk about that.'"

These revelations led to protests by Chinese-Americans who, fearing the worst, are likely imagining an otherwise unimaginable class of human rights violations. "There are red flags popping up all over the place," said city Supervisor Fiona Ma, a Chinese-American herself. She's now working to shut down the show and to bar such exhibits from the city without clear proof of the donors' consent.

But those flags have been flying high for the past two months. A reporter from the San Francisco Chronicle sent to the exhibit before its opening was given a terrific runaround by its promoters when she tried to find out the origin of the bodies. She was told only that most were donated to science, though some were "unclaimed."

Coincidentally, "The Universe Within" opened in San Francisco on March 31, the day Terri Schiavo was officially pronounced dead -- a moment when corpses and our moral obligations about how to treat them were at the center of the news. In retrospect, it's amazing that a giant room full of controversial cadavers slipped under the radar of our culture of life for so long. Especially a room full of corpses like this these -- a flamboyant bunch that cavalierly blur the line between science and pure spectacle. I visited last month and found the whole thing exhilarating, God help me.

Despite all its educational pretensions, "The Universe Within" is overwhelmingly a work of art. The potted tropical foliage, the theatrical lighting design and the piano music are all part of it. But most of all, it's the impishness of whoever's turning these bodies into sculptures.

Plastination preserves all the nuanced bumps and wriggles of body tissue, sustaining its appearance and allowing the bodies to be easily posed. These are not skeletons or mummies but recognizable humans with skin, fingers, lungs, spleens, tongues, privates, eyelids, even eyelashes, and often enough face left to make things unsettling. Just how much face is up to the curators who have carved up and peeled these folks open with the panache of wedding florists.

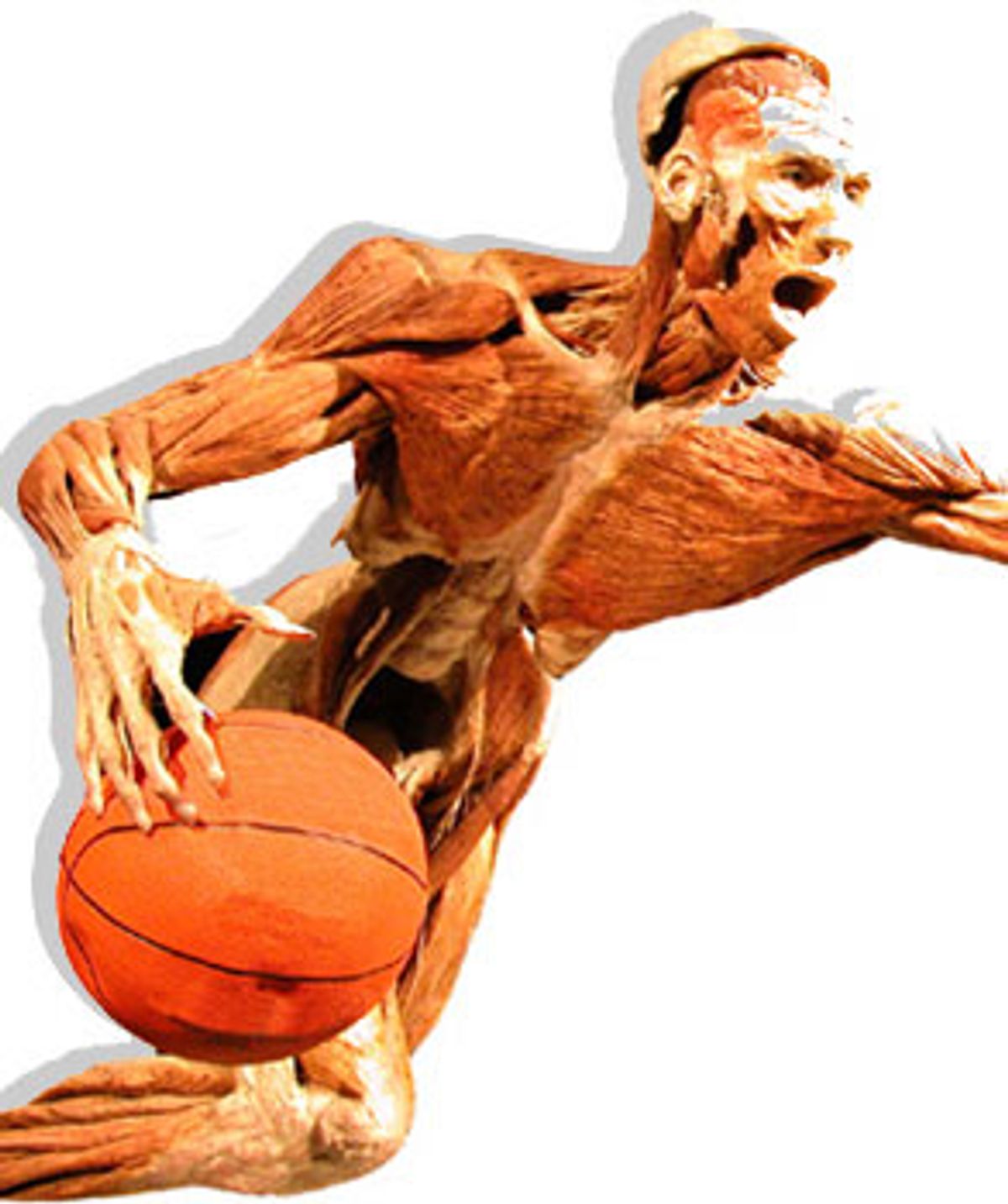

It's with a certain baroque flair that one plastinated dead body rides a shiny blue bicycle with "Forever" decaled on its frame. And what about the man next to him, the one holding out a sagging jumpsuit of his own skin on a wooden hanger -- that's meant to be ironic, right? I didn't quite know what to make of the guy sawed vertically down the middle, each half stepping forward to shake hands with the other like forthcoming husbands at a barbecue, nor the man charging at me with reddened plates of freed muscle splaying wildly off his body in all directions, the way radishes are carved into roses.

Such mordant morbidity is apparently de rigueur for plastination exhibits. (Some poses are apparently taken straight from von Hagen's "Body Worlds," which also features a fleshless corpse turning freestyle skateboard tricks.) But what's peculiarly unsettling about "The Universe Within" is how little information is put forward.

The diagrams next to the bodies seem largely arbitrary. One bears the heading "Digestive System" and points out things like the clavicle deltoid muscle, biceps brachii, and quadriceps femoris muscle -- none of which, of course, digest. There are no clunky blocks of prose explaining what the highlighted body parts do, and the partially fleshless corpse rearing back to pitch a bright new Rawlings baseball in the center of the room doesn't even get a write-up. He's just a dead man throwing a ball, you see.

I can't say all of this didn't seem suspicious at the time, and I began to feel that leaving "The Universe Within" without a nuanced edification of physiology would somehow dishonor the people, the bodies, who had made it possible. I tried to eavesdrop as the occasional medical student or professional would start explaining respiration or cardiac arrest to the group of friends he or she had doubtless dragged there.

But I also noted that "The Universe Within's" mission statement stops short of offering any exhaustive education, rather aiming to "stimulate interest in and create a new awareness of the wonder that is the human body." That is, these bodies may be intended to spark a curiosity more than satisfy it. And it seemed to me there should be a place for just this type of scientific outreach, where the volume of facts isn't necessarily given a premium over a general sense of wonderment.

I began to think of "The Universe Within" as a kind of secular reliquary -- like Rome's crypt of Santa Maria della Concezione, where room-size mosaics have been fashioned from the bones of thousands of Capuchin monks; or St. Catherine's glass-encased hand in Siena; or the slumped body of St. Boniface in Prague. The believer was meant to feel earnestly, if not quantifiably, inspired in the presence of these relics. Seeing a cadaver hitchhiking or a plastinated lung -- a real lung for chrissakes! -- filled me with a not so dissimilar, almost religious exuberance.

"I don't think you're wrong to think that," Michael Sappol, a historian at the National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Md., and the author of "A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth Century America," told me later by phone. "You're not wrong to be amazed, to feel, This is my body. And you're not wrong to look at a dead body and think, This is death."

Sappol speculates that plastination exhibits are alluring in part because "we live in a sea of body images that are constantly trying to trump each other in terms of novelty or beauty. Because we can't directly see into our own interior, there could be nothing more novel." Yet we also live in a culture intent on hiding death; and these exhibits flaunt it. "You're seeing yourself, but you're also seeing a monster at the same time."

Plastination exhibits follow a long tradition of spectacular anatomical displays that channel this basic curiosity. These range from dissecting humans in a public "anatomical theater" in the 1600s, often for the pleasure of civic dignitaries, to grotesque cadaver exhibits in the dime museums of 19th century New York. Creeping alongside this continuum, however, have been debates (and sometimes riots) over the provenance and rights of those bodies, similar to the arguments erupting now around "The Universe Within." After all, it was common for 19th century doctors to resort to grave robbing for their specimens -- only because there was an inadequate supply of executed criminals and unclaimed vagrants, who were fair game.

In America today, the widely revered principle to adjudicate the use of cadavers is informed consent: Donors must sign off on precisely how their bodies will be used. This is effectively what Fiona Ma is battling for. Sappol calls enforcing it with respect to exhibits like "The Universe Within" a matter of justice, saying, "It's very unlikely that von Hagens or these plastination people can meet any kind of informed consent." That is, it's unlikely a man somewhere in China volunteered specifically to be the skinless fellow riding a bike. Sappol also cited reports of organ harvesting from executed Chinese prisoners.

But Sappol admits he's ambivalent about the idea of applying that standard retroactively. Informed consent, like all other concepts in bioethics, is relatively recent, having arisen only after donating one's body to science became a prestigious, upper-middle-class bit of altruism rather than a haphazardly forced arrangement for the destitute. "Every major anatomical museum would have to take things off display," Sappol said. Just two years ago, the skeleton of a slave in Waterbury, Conn., which had been turned into a medical model by his physician owner and displayed in a local museum for generations, was finally given a proper burial. (Connecticut also commissioned an operetta to honor the slave.)

The ethical controversy surrounding "The Universe Within" may undermine any esoteric argument about art, science and the value of wonder. The excesses of the exhibit itself certainly can't be justified for their power to instill reverence for the human body if the curators have so basically betrayed that reverence by hijacking bodies and then lying about it. The paradox is, an exhibit that so forcefully inspires curiosity about "the body" also seems to have a strange power to neuter curiosity about the individual bodies staring us in the face.

So it may turn out I was complicit in the handiwork of body-trafficking hucksters, ponying up $15 and shuffling around the gallery with my jaw dropped, exclaiming over how marvelous it all was. And I can't say I don't feel pretty filthy about that. The things that amazed me most, while still amazing, are also now vaguely haunting. That flank steak, for one. Or consider the hot fuchsia filigree of arteries that the curators of "The Universe Within" had extracted from a leg to be strewn across the blue velour of a rectangular display case. Consider how the filaments still hold their leg shape, like a knit sock that has nearly worn away. But also consider that it was a toddler's leg. And a few short wisps of its artery had flecked free of the mass and were, as I stood there gawking at it, static-clinging to the velour -- just kicking around, like bits of a cheap feather boa after a costume party.

Shares