The shock of Jean-Claude Brisseau's "Secret Things" has less to do with what we see -- copious nudity, lesbian scenes, threesomes, public masturbation, incest and a hardcore orgy -- than the movie's unfashionable level of seriousness and ambition. "Secret Things," the first of Brisseau's films to be released in the U.S., has been talked about as if it's the latest in French cinema's ongoing series of provocations, a list that encompasses the work of directors as talented as Catherine Breillat ("Romance," "Fat Girl") and as fraudulent as Gaspar Noé ("I Stand Alone," "Irreversible"). The movie is a French provocation, but one whose lineage is Choderlos de Laclos and (fleetingly) the Marquis de Sade.

Not only is Brisseau's narrative classically structured -- this is a rags-to-riches story about the material and social rise and moral fall of its protagonists -- the film has a deepening sense of consequence. Souls, if not lives, are hanging in the balance here, and Brisseau takes the ideas of corruption and damnation very seriously. At times the movie feels like an updated version of a scandalous 18th century novel, the sort of thing Roger Vadim accomplished in his 1959 retelling of "Les liaisons dangereuses" starring Jeanne Moreau and Gerard Philippe as a modern, bourgeois Merteuil and Valmont.

Brisseau risks ridiculousness and sometimes teeters right on the edge of it. This is a director working in a contemporary setting and in a (deceptively) naturalistic style who, in some scenes, includes a hovering Angel of Death, replete with raven. We still accept stories about people destroyed by fate or by their own flaws in opera and in novels of past centuries. But in a contemporary setting we tend to find those same potentialities silly, as if this scale of passion or hubris is something that we've collectively and sensibly outgrown in favor of Wes Anderson comedies.

Which may be why some of the advance reviews of "Secret Things" suggest that critics are content to enjoy the movie as long as it's the cool, cynical comedy of sexual manners it starts out as. As soon as it becomes clear that there are human casualties of the power games the two female leads are playing -- that is, as soon as the movie becomes more than an elegant, art-house turn-on -- those same critics start talking about how nutty and overheated it is.

But the tone shift that Brisseau engineers in "Secret Things" is essentially the same as the one de Laclos employs in "Les liaisons dangereuses," which seems to be the movie's main inspiration. Nathalie (Coralie Revel) and Sandrine (Sabrina Seyvecou) meet working in a strip club (Nathalie as a dancer, Sandrine as a bartender) and are fired on the same night for refusing their boss's attempt to pimp them out to a customer. Unable to pay the rent on her room, Sandrine moves in with Nathalie, who decides to use the sexuality that makes her the focus of attention when she's performing to haul herself and Sandrine up the corporate ladder.

The early scenes of the more experienced Nathalie instructing the novice Sandrine in how to be a corporate courtesan recall the licentious comedy of Pietro Aretino's "The School of Whoredom." Nathalie explains to Sandrine how to seduce without being seduced, and warns her that love is Public Enemy No. 1. She tells Sandrine that, above all, she has to dare, and this becomes a series of challenges during which she prods Sandrine to masturbate on a subway platform, or to walk around with nothing under her trench coat and to feel superior to the people constricted by their clothes and undergarments.

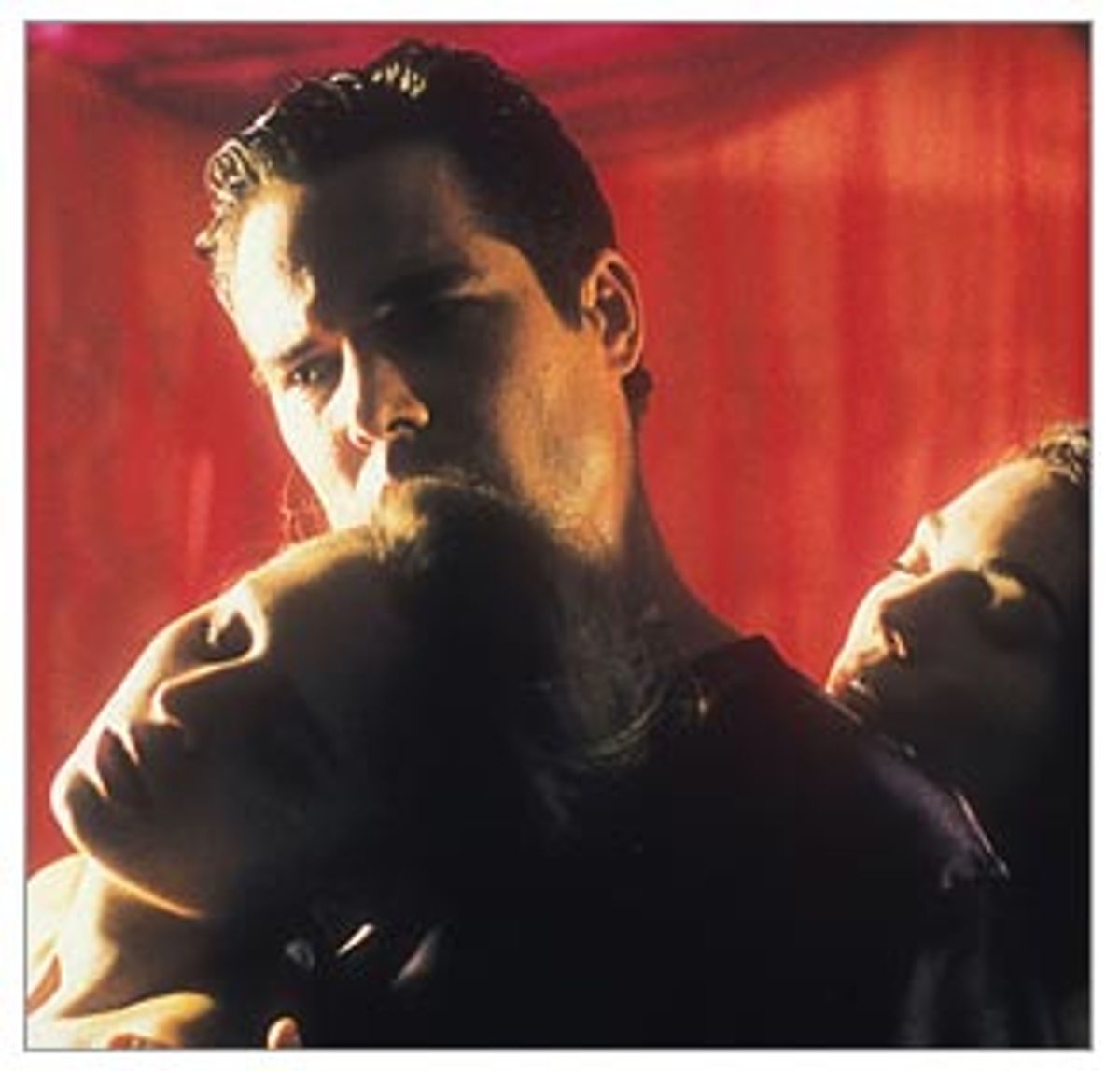

The story proceeds as a fable, confirming Nathalie's logic of sex as power. That power is enough to secure them jobs with the same company on their very first interview. Sandrine's boss Delacroix (Roger Mirmont, evoking sympathy for a character who could easily seem dull), a decent man who's never cheated on his wife, is an easy target for her newly acquired wiles and the two are soon sleeping together. Sandrine's ultimate target -- and Nathalie's -- is Christophe (Fabrice Deville), the boss's son, a smooth-faced brat who has had every privilege handed to him as a birthright and who has the gall to say, "Society proves every day that merit is all that matters."

Needless to say, Christophe's words become the metaphorical knife that Nathalie and Sandrine wield on this arrogant clod. But like so much else in "Secret Things," the meanings remain elusive. Brisseau has not conceived "Secret Things" as a feminist revenge tale. The implied feminist critique --- that women have to use their sexuality to gain power in the male-dominated business world -- is superseded by the film's critique of power. Brisseau does not allow us the comforts of either libertinism or moralism. He doesn't pretend that Nathalie and Sandrine don't give up a part of their souls when they decide to prostitute themselves for power. Prostitution is the controlling metaphor for capitalism here, as it was in Jean-Luc Godard's "Vivre sa vie" and "Two or Three Things I Know About Her," but without Godard's implicit condemnation. Brisseau knows that there's no revolution coming to overturn the capitalist order.

In terms of the world the movie shows us, Nathalie and Sandrine are acting logically. They are not innocents, buffeted helplessly by fate or society, but free agents who have chosen to make their play for success. When Sandrine arranges for Delacroix to find her and Nathalie making love, it's for the implicit purpose of humiliating him sexually and consolidating her power over him. Their actions are cruel and calculated, and yet Brisseau does not allow us to judge them. The choice they have is how they'll prostitute themselves -- pimped out by the strip club owner, or controlling what they get out of the exchange? That's a cold choice, but the fate of Nathalie, who turns out to be much better at formulating strategy than carrying it out and who breaks every rule she set up for seduction, doesn't seem much better. Revel gives the movie's best performance, the steely control evident in her eyes gradually replaced by the zeal of an avenging romantic wraith. Seyvecou's role calls for her to reveal the capacity for manipulation inside her demure exterior, and she's fine but a little bland. (The younger Sandrine Bonnaire, or perhaps Julie Delpy, would have been perfect in the part.)

"Secret Things" is a damnably slippery picture to get a hold of. Much of it takes a deliberate middle course, declining any of the positions that would make it easy for us to tie the tale up into a tidy lesson. Brisseau refuses both a distanced, purely intellectual approach and an exploitive one. And though the film appears to be realistic, it has a touch of the fantastic from the start. Nathalie's strip-club routine, which opens the film, is more like erotic performance art. It's too bad that the look of the movie doesn't reflect the firmness of its tone. Wilfred Sempe's cinematography is fine, but it lacks the burnish, the diamond hardness, that would make the corporate world both sinfully alluring and inhuman. (The offices all look rather shabby.)

Brisseau needs to allow for the baroque elements as he sets up the last section in which Nathalie and Sandrine finally come up against Christophe and the film moves into full-blown operatic melodrama. It's crazy all right, but no crazier than Christophe himself. He's the character who has taken a lust for power to an insane extreme. This arrogant rich kid turns out to be a Nietzschean superman who, after surviving a childhood tragedy, believes that he's invincible. His preferred dress for his sexual encounters are flowing silk shirts and robes that make him look like a louche ancient Greek. Christophe uses people so consciencelessly that he's driven several of his lovers to suicide. (When a woman turns up at one of his orgies and douses herself in gasoline, his guests calmly file back inside -- they've seen this before.)

It's at this point, I think, that viewers either decide to go all the way with the movie or, as some critics have, take refuge in calling it the "desperately French equivalent of an early '90s, straight-to-video Joan Severance or Shannon Tweed title" or "rococo and cuckoo" or "ridiculous ... the greatest soft-core porn movie ever made." Had Brisseau stopped short of the extremity of his conclusion, "Secret Things" might have seemed too controlled, too smugly sure of itself, a movie about game playing that itself was nothing more than sophisticated, disengaged game playing. Brisseau isn't willing to make Nathalie and Sandrine mere pawns in his scheme. He takes the fate of their souls very seriously. Why, he might ask, would you bother to make a movie about characters whose fates you didn't take seriously? And that's not a hip stance at a time when wiseass irony is king.

"Secret Things" is not a great movie, but its daring and seriousness, its refusal to take refuge in the sort of irony that diminishes whatever it touches, its willingness to risk ludicrousness, may be elements that are necessary to achieve greatness. They are also not widely shared values in movies right now. A.O. Scott addressed this state of affairs in his New York Times review of "The Dreamers" when he said that sophistication has come to mean rejecting emotion. Sometimes reading film critics now, I feel like I'm reading a bunch of high-school kids determined not to do anything to embarrass themselves in front of the cool clique. They seem to live in terror of someone asking them, "You took that seriously?"

I think that fear helps to explain the belittling tone you can read in some of the reviews of movies as diverse as "In America" and "The Dreamers." (J. Hoberman's Village Voice review of the latter ridiculed the very sort of passionate cinephilia he once might have been expected to understand.) It explains why it's easier to praise the stultified prestige filmmaking of "Cold Mountain" and "House of Sand and Fog" (isn't that title enough to warn anyone off?). And it certainly explains the reviews intent on turning "Secret Things" into an overheated, flamboyant skinfest. I get the feeling that it would be easier for some of those critics if they could just say "It's nutty! It's sexy! It's French!!"

What this means, I think, is that allegedly sophisticated audiences have come to distrust emotion, and are unable to distinguish between artists who use it fearlessly and the Hollywood schlockmeisters who manipulate it crassly. And it's not just emotion that isn't trusted but ambition. Maybe some audiences don't find ambition and daring appropriate to an age of diminished expectations. But diminished expectations become a self-fulfilling prophecy when everything is expected to remain small-scale, ironic, hip and distanced. God knows it's hard for any filmmaker, here or abroad, to break out of the strictures that the studios want to impose. But it would be wrong to claim that those strictures are coming from the moneymen alone. If greatness and emotion and daring are foreign concepts in movies right now, part of the problem has to be that critics and audiences have made it so.

Shares