Arturo Pirez-Reverte's novel "The Club Dumas," the basis for Roman Polanski's new film, "The Ninth Gate," is one of those books that you can't help imagining as a movie while you read it, even though it would appear to be nearly impossible to film. The solution to the novel's mystery is fairly obvious. The pleasure comes from its literary gamesmanship -- it helps to know who Irene Adler is, or why a burglar hunting for a rare Dumas manuscript would leave a Montecristo cigar as his calling card -- and even more from the way it captures the nuttiness, and the nastiness, of people who love books.

Pirez-Reverte's hero, Corso, is a "book detective," a mercenary hunting down rare books for the collectors who itch to possess them. In the course of seeking out the three existing copies of a book said to contain the means of summoning the devil, Corso finds himself seemingly living out the plot of "The Three Musketeers." The book detective becomes ensnared in an intrigue that's a sly joke on both the fantasies and the isolation of constant readers. Pirez-Reverte's characters, devotees of Dumas and Conan Doyle and Dickens, sneer at the way "serious" fiction has largely abandoned the pleasures of plot (the author shares their contempt) in favor of the tedious nonnarrative of personal observation. But it's almost a case of "Be careful what you wish for" when Corso's life is lifted above tediousness into what he calls "a serial that somebody's writing at my expense."

"The Club Dumas" is unusually generous entertainment, a pop metafiction that's also a portrait of the far-from-benign acquisitiveness of book collectors. Corso encounters people who have amassed thousands of volumes without apparently opening one, fetishists for binding or the quality of paper. The most poignant person is the final descendant of a once-wealthy family, living alone in his ruined mansion, his existence devoted to tending his remaining volumes. He survives by selling two or three a year, each sacrificed as lovingly and obediently as if he were Abraham doing God's sadistic bidding.

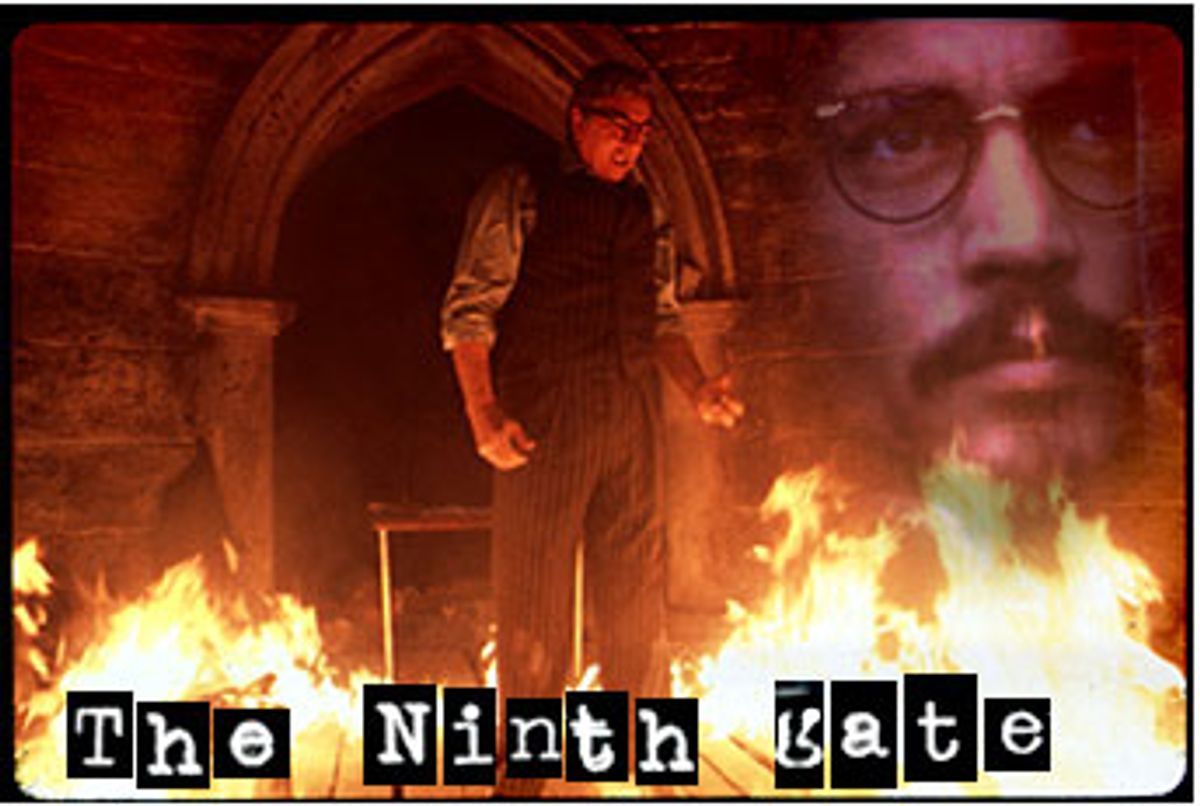

It's no surprise that Polanski and his co-screenwriters, Enrique Urbiz and John Brownjohn, had to pick and choose in adapting "The Club Dumas" into "The Ninth Gate." The parallels to "The Three Musketeers" have been entirely jettisoned, and characters have become composites. The plot now has to do entirely with Corso's search for the satanic texts. But beyond the disappointment and dislocation that are inevitable when a good book is changed for the movies, there's a pretty good time to be had with "The Ninth Gate." It's not exactly a good movie. Polanski's approach is airless and a little pokey, and you can't always be sure he sees the ludicrousness of the devilish goings-on. (After orgies, nothing looks as consistently silly in movies as satanic rites.) But until the very end, when it indulges in one flourish too many, "The Ninth Gate" is amusing, ultra-deadpan entertainment. The director was lucky enough to have a cast who were in on the joke and tuned in to his wavelength.

Polanski seemed to pour everything he had to say about a life marked by violence into his last picture, 1994's devastating "Death and the Maiden." It's understandable that he would now take refuge in the elegance of his craft. "The Ninth Gate" is an extremely well-made movie. Despite a few slow spots, the pace is just about perfect. A mystery centered on books should unfold at a tempo different from the pell-mell acceleration to which movie thrillers have accustomed us. And though the opening scenes have been relocated from Madrid to New York, Polanski and cinematographer Darius Khondji have given the city a sinister Old World air. It's all ominous brownstones and narrow streets. You wouldn't be thought foolish to imagine eyes watching from dark doorways or behind curtained windows. When Corso, played by Johnny Depp, stands in the private chamber where the wealthy book collector Boris Balkan (Frank Langella) has stored his treasures, the nighttime cityscape beyond the glass windows looks like an elaborate facade, as if the modern world were no more than an illusion, a storyteller's construct.

Looking for a replacement for Pirez-Reverte's literary allusions, the screenwriters have introduced the conventions of old movies. As one of the hounds on Corso's tail, Lena Olin does a pretty good femme fatale, balancing parody with enticement. (She's much more game than the bloodless, deeply boring Emmanuelle Seigner as the mysterious girl who becomes Corso's protector.) And there's a great moment when Depp delivers the most movie-ish of lines, "Stay here and cover me -- I'm going down," as if he can scarcely believe he's saying it, and secretly tickled that he got to. But these substitutions feel halfhearted, too tacked on and intermittent to work as a fully developed satirical idea.

The movie could use more oomph. Polanski's jack-o'-lantern leer has always been a mite dry. He's so at home with his perversities that they don't carry a jolt. (When one of the characters turns out to be one-handed, you know it's only a matter of time before Polanski shows you the stump.) For "The Ninth Gate" to really sing it would take a degree of playfulness and energy that doesn't suit Polanski the stately, grotesque prankster. Still, he tosses off the macabre touches -- a submerged corpse surrounded by swimming goldfish, a woman descending a staircase so rapidly you can't be sure whether she's sliding down the banister or floating -- with such nonchalance that the images linger. The mood they establish bleeds into the rest of the movie, creating an atmosphere of handsome unease.

As usual, Polanski's grotesquerie is embodied in the casting, particularly Barbara Jefford, who hisses like Conrad Veidt in "Casablanca" as one of the collectors Corso calls on. (You wouldn't be surprised if she crooked a finger and admonished, "Be-vare!") Jefford, wisely, doesn't even attempt to be subtle, and Polanski rewards her with a spectacular finish, one worthy of Miss Havisham. (As the ruined book collector protecting the remnants of his cherished collection, Jack Taylor acts in another mode altogether, the poignancy of humbled privilege.)

Nothing seems impossible for Depp as an actor, except losing his dignity or appearing out of place. He can lend himself to a filmmaker's most fantastical ("Sleepy Hollow") or poetic ("Dead Man") conceptions and turn into the embodiment of those flights of fancy, anchoring them to earth. From our first glimpse of him, as he screws a greedy bourgeois couple out of a book collection, Depp is right in tune with Polanski's dry malice. Depp's performance here is so understated it's nearly subterranean. There's a flicker of amusement, but it's deep down. Chain-smoking crumpled Luckies and downing scotch, and done up in round glasses, graying hair and a mustache and goatee (in a disheveled state he looks like a matinee-idol version of Leon Trotsky), Depp looks as lean and hungry as one character describes him. His unflappability as the corpses pile up and the whole enterprise gets stranger and stranger becomes the movie's running joke. It's a sleek, mischievous performance.

But Langella as the collector who sets Depp on his course is the prize ham in this piece of elegantly appointed hokum. Bearing an amusing resemblance to Gore Vidal (and wearing huge eyeglasses that look like one of Swifty Lazar's rejects), Langella pops up with the larcenous assurance of a practiced scene stealer. Most of the time he appears only with Depp, who more than holds his own, and it's a good thing: Langella looks ready to walk off with the whole movie in the pocket of one of his tailored vests. It's a delicious turn. Langella exudes the purring malice of a house cat who has gotten more cunning and more cruel with age, one you'd never think of getting rid of. You wouldn't turn your back on him for a minute, but he makes a hell of a conversation piece.

Shares