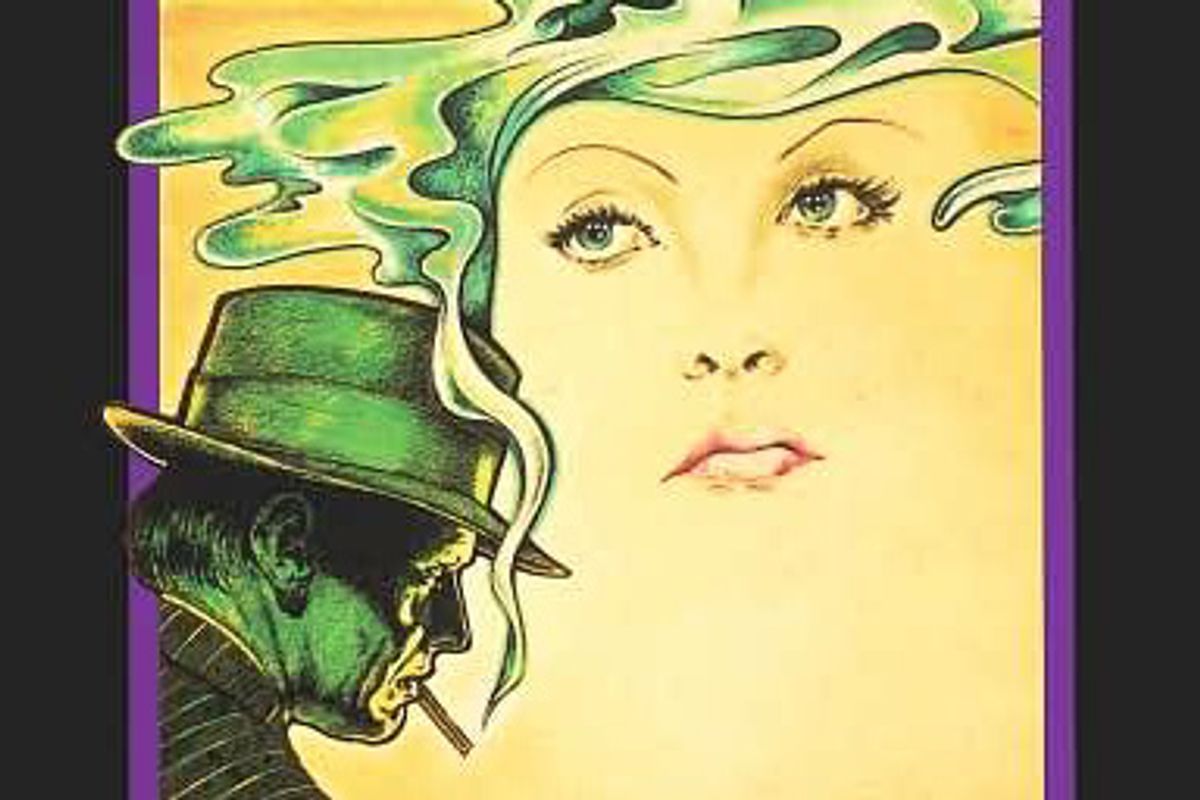

In case you're wondering why the arrest of a 76-year-old man for a sex crime committed 32 years ago has provoked a world-historical display of stupidity and sanctimony on all sides, the answers, such as they are, can be found in "Chinatown." By pure coincidence (I think), the genre-defining 1970s neo-noir is the latest DVD release in Paramount's Centennial Collection, hitting the street barely a week after its director was detained in Zurich, pending extradition to the United States.

If "Chinatown" is the greatest of all American detective films -- and I think the case is a very strong one -- then that results from its remarkable confluence of ingredients: Career-best performances from Jack Nicholson, as witty and thin-skinned private eye J.J. Gittes, and Faye Dunaway, as the promiscuous and damaged California WASP wife who either does or doesn't hire him; an unusually intelligent and engaged producer, Paramount's legendary Robert Evans; a script loaded with the pain and nostalgia of Los Angeles history, from native son Robert Towne. Oh, and then there was the director, a phenomenal European craftsman who didn't much want to come back to L.A., because he already knew too much about the terrible things that could happen there. What was his name again?

"I wasn't very hot on going back to Hollywood and making a movie there," Roman Polanski says in a laconic 2007 interview excerpted on this double-disc set. Presumably if he'd resisted the entreaties of his friends Nicholson, Evans and Towne and stayed in Rome, then "Chinatown" would never have been made and nobody outside Samantha Geimer's family would ever have heard of her. Would Polanski have directed a different great film, and abused some other young girl? Hypotheticals like that get us nowhere, which makes them nearly as pointless as the noble intentions -- the desire to see vice punished and virtue rewarded -- that lie at the heart of so many doomed human endeavors, in life as in "Chinatown."

Towne's original script, he tells us in an accompanying featurette, included no scene actually set in L.A.'s Chinatown; it was Polanski who insisted that the movie's racially tinged guiding metaphor had to be made explicit. After Nicholson's Jake and Dunaway's Evelyn Mulwray finally go to bed (for the one and only time), he tells her that he used to be a cop in Chinatown, where "you never really know what's going on." He once tried to protect a woman there, and only ended up making sure she got hurt. "Dead?" Evelyn asks him, and then the phone rings. It's the end of the movie calling. We never hear the rest of the story, but we don't need to: By telling us what happened before, Jake somehow makes sure it's going to happen again.

As Towne puts it, "Chinatown as a notion begins to stand for the futility of good intentions." In the film's final scene -- largely crafted on the fly by Polanski, Nicholson and Towne -- Chinatown becomes the place where Evelyn Mulwray will die, and where her daughter (and half-sister) will be delivered into the arms of her monstrous father (and grandfather), the water-and-development tycoon Noah Cross, played by John Huston as an amazing blend of evil and simian intelligence. It's a crushing conclusion, one from which many viewers understandably recoil, and Towne had originally proposed a different ending: Jake and Evelyn would engineer the murder of Noah and keep silent about the incest. The girl would be free from the man who raped her mother and might well intend to rape her, and if Evelyn had to go to prison (or the gas chamber) then so be it.

It's tempting to speculate that Polanski imposed his own pathologies on the picture, but for whatever it's worth Towne now says that he agrees with the director's view: "I think Roman was right. A story with that degree of complexity needed the clarity and simplicity of the ending that he saw."

As for Polanski himself -- well, all you can say about that 2007 interview is that the concept of irony doesn't begin to cover this situation. Every topic he addresses, from his dislike of Los Angeles to his observations on guilt and morality, seems to encompass an unconscious, almost leering, double meaning. As usual, the man who has jokingly called himself "an evil, profligate dwarf" doesn't make much of a character witness in his own defense, with his dry, bemused, superior manner. On the ending of "Chinatown," he says, "That's how it is in life very often, that the culprit survives ... You have to give people something they can think about. If everything is wrapped up in a happy ending just because the merchandising people prefer it, the audience leaves and forgets about the problem right over their dinner."

It's natural enough that "Chinatown" will be contaminated, perhaps forever, by the infamy of its director, and it's difficult to watch it without supplying invisible exclamation marks. Here's Polanski himself, playing the wicked little thug who mock-castrates Jake, slicing open his nose with a switchblade (!). (Nicholson improvised the line: "Where'd you get the midget?") Here's the immortal line spoken by Huston, a real-life aging lady-killer director (!) playing an aging pervert (!) offering an explanation about how and why he raped his own teenage daughter (!): "See, Mr. Gits, most people never have to face the fact that, at the right time and right place, they're capable of anything." (!!!) Et cetera. You have to hope all that doesn't stop people from appreciating the masterly economy of Polanski's shot construction and editing, the luminous, edge-of-hysteria performances by Nicholson and Dunaway, the affecting and surprising trumpet score by Jerry Goldsmith.

I am not claiming that a work of art has nothing to do with the person who made it, since that's a stupid idea, and I'm certainly not claiming that the work of art is somehow co-guilty of its creator's crimes, since that's an even stupider idea. (Wagner's music will always be identified with fascism; it can't be reduced to fascism.) I am certainly not speaking out in defense of Roman Polanski, who apparently did something that was both heinous and illegal, and should long ago have faced the consequences. I guess I'm saying that it's hypothetically possible to learn something from a movie, and totally impossible to learn anything from the sordid private lives of celebrities.

Furthermore, I'm saying that Polanski's most hysterical attackers, the ones who can't decide whether to gouge out his eyes before or after boiling him in oil, and his most tone-deaf defenders, the ones who wonder whether, y'know, it might not have been rape-rape, are responding to the same social truth identified in "Chinatown." Terrible things happen in all sorts of ways and in all sorts of places -- in Hollywood and Washington and at the mall and on Maple Street -- to girls and boys and women and men, and all too often "the culprit survives" and the authorities do "as little as possible," to use Jake's final words in the movie.

Does it serve the cause of justice for Roman Polanski to come back and serve time? Jesus, I really don't know. He did a very bad thing, but at this point he's become a symbol, and that's never good news. We can decide to "take him out back and shoot him," in the edifying phrase of Cokie Roberts. But, seriously. Does focusing all this rage and resentment on one pervy old Polish movie director somehow make up for all the other times we've been cheated and lied to and robbed and abused and raped (metaphorically or otherwise) by people in power, and then had to stumble away down the street in stunned disbelief while some allegedly well-meaning person patted us on the shoulder and explained that there was nothing to be done, we didn't understand, it was the way the world worked, we just had to suck it up and keep our heads down. Does it make up for the moment of godawful insight as his protagonist vanishes into the crowd at the end of his greatest film? "Forget it, Jake. It's Chinatown."

Shares