Hollywood has a drug problem. For all the dope movies, for all the films about cops or junkies, kingpins and double-dealing DEA agents, there's never been a single mainstream movie that's been big enough, ambitious enough to go after the drug war itself.

Steven Soderbergh's "Traffic," which opens Christmas Day in New York and Los Angeles, is that movie. If films like "Drugstore Cowboy," "Rush" or even "The Man With the Golden Arm" have been orbiting planets, self-contained units that dissect or examine one facet of drug use or the war on drugs, "Traffic" is the solar system.

Perhaps even more notable, "Traffic" is the first mainstream, major Hollywood production that has come out and said that America's drug war is not winnable. The film argues both implicitly and explicitly that going after the suppliers and the drug traffickers -- where the U.S. spends the bulk of its $19-billion-a-year budget -- simply doesn't work, that it kills innocents and turns others into criminals, that it devastates poor neighborhoods, that it can't stop or even attenuate an insatiable social maw of illicit drug use.

"Traffic" is a huge, determined movie in every way. Stephen Gaghan's original 165-page script, loosely based on the 1989 British miniseries "Traffik," contained 130 speaking parts. It was shot in nine cities on 110 locations and cost $50 million to make.

The result is an exciting movie to watch, one that has the potential to draw a wide audience. As a director, Soderbergh's a Hollywood golden boy; he's riding the critical and commercial success earned from such varied films as "Out of Sight" (a silky, surprisingly sexy caper film); "The Limey" (a fractured, postmodern gangster noir); and the blockbuster "Erin Brockovich" (a smart and crowd-pleasing classic Tinseltown entertainment).

Even amid the clutter of Christmas releases, "Traffic" could be the one film that plays through April. The early reviews are strong; several critics have included it on their year-end top-10 lists. Last week it won best picture and best director from the New York Film Critics Circle -- an early sign that the film could earn a few Oscar nominations.

"Traffic" tells three stories at once. Michael Douglas plays an Ohio state Supreme Court justice appointed drug czar by the president. He (and, by extension the audience) quickly comes to appreciate the octopus-armed enormity of the drug problem and the complicated skeins of American law enforcement tied together to fight it as his daughter turns a taste for cocaine and heroin into an addiction.

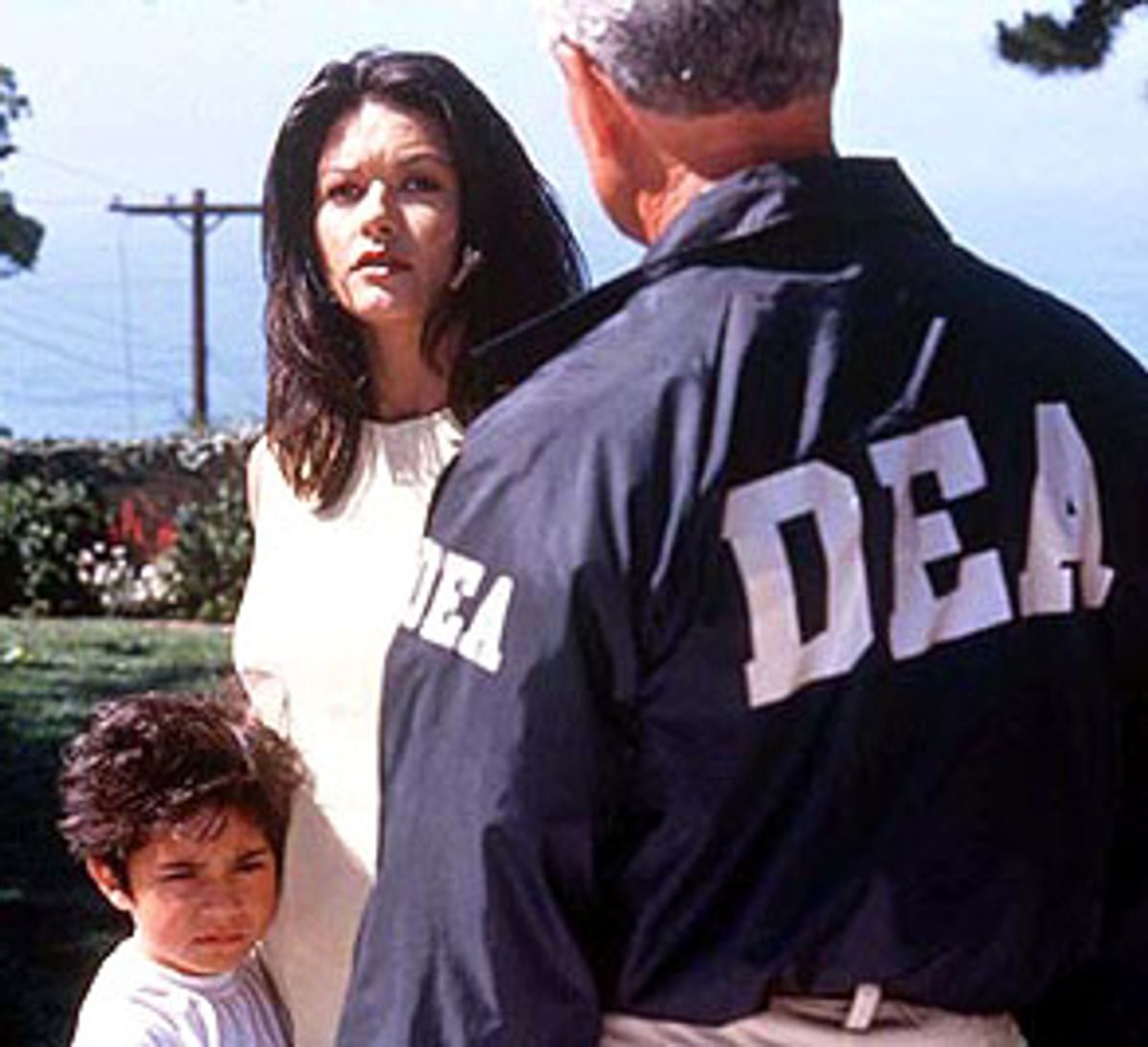

In the second story line, Catherine Zeta-Jones plays the society wife of an American cocaine importer busted by the DEA; she was unaware that he was moving drugs. The bust threatens her husband's self-made American dream and the future of her children, and she must make a decision to help her husband or remain a bystander. In the third story, Benicio Del Toro is a Tijuana cop who with his partner gets caught up in a battle between two Mexican drug cartels. Both are more or less good guys who can't avoid getting swept up by one side. When Del Toro finds out he's being used, he has to figure out a way to save himself and his partner.

The stories all intersect at certain points: The drug czar recruits the same Mexican general who employs Del Toro; and an assassin from the Mexico thread ends up in the Zeta-Jones story. Cumulatively, the stories convey the disturbingly sticky problems caused by drugs in America and the grimly determined but bloodily feckless efforts to control them.

At the same time, these characters are merely the interstices of a dizzying panorama of characters: including users, addicts, social workers, counselors, cops, DEA agents, custom officials, mules, dealers, midlevel traffickers, kingpins, soldiers, assassins, reporters, prosecutors, lawyers, politicians, judges and czars.

Soderbergh effortlessly herds these characters and themes, using both the trenchant structure of Gaghan's script and a variety of filmmaking techniques -- changing the colors of the film between each of the stories is just one. If you don't know what's going on, like when local cops crash a DEA bust, it's because you're supposed to be as confused as the characters.

Moving from city to city, into cheap hotels, across the White House lawn, through country clubs and across the U.S.-Mexico border, "Traffic" feels like a documentary or a nightly newscast. (Soderbergh and Gaghan met with and interviewed the same policymakers and cops who appeared in the film as themselves or as characters; in addition, New York Times investigative reporter Tim Golden was a consultant.)

It's a thrilling movie because it feels so real. Most of the hand-held camerawork, shot by Soderbergh under an alias, provides a rushing sense of immediacy. You're there, inside the news, watching it happen to and because of real characters -- characters you care about, characters who are as complicated and flawed as the real thing.

But the entire point of "Traffic" is that it is bigger than its characters, and that's what makes the movie so important: It's a film that's moved beyond laying out the facts and letting its audience sort them out. Soderbergh and Gaghan have a clear opinion and neither are holding back -- they're not afraid to risk sounding didactic in service of what they consider a moral high ground.

Some critics have claimed that "Traffic" is flawed because it doesn't really offer any solutions. They're wrong. In the Douglas sequence -- the emotional center of the film -- Soderbergh suggests that the only way to deal with the drug problem is on a human-to-human level. The grand war is more preposterous than a quagmire like Vietnam. It's worse because here we fight our own families. If people do drugs, and they will, always, legal or not, some of them will become addicted to drugs. And if they become addicted, they need to get treatment, and they need attention and they need support.

In interviews promoting the film, Soderbergh says that neither he nor most of the people he spoke with think that drug legalization will happen anytime soon. He favors treating drugs as a health issue, not a criminal one. Soderbergh knows it's not a sexy subject, but he obviously thought enough of it to include it in an already sprawling story.

Sure, Soderbergh is far more interested in the problem, and the hypocrisy, of the drug war. Douglas repeatedly dips into his Scotch, and a half-dozen Congress members and politicians chatter away at a cocktail party. The film never says that alcohol and tobacco kill more than half a million people a year, while coke and heroin kill 3,000 and marijuana none -- it doesn't have to.

You could also fault Soderbergh for not really showing why regular people do drugs, or trying to show that drugs are pleasurable, life-changing, relaxing or fun. In this film, the only civilians we see do drugs are a few prep school teenagers. Of them, one has some sort of seizure and another becomes a whoring junkie. But at the same time, you could argue that Soderbergh knows that most of the people in his audience have used drugs: More than half of high school graduates have, there are an estimated 80 million users and the drug trade is worth more than $200 billion a year.

Soderbergh does better on the resource issue. The Mexican cartels are far richer and better outfitted than both Mexican cops and the most sophisticated branches of American law enforcement. The traffickers are also more ingenious, more technologically advanced and more ruthless -- plus they reap huge financial rewards. They'll throw drugs at the border, knowing that some of it will make it and some of it won't, and that the profits will more than cover the losses in any case. It's like a big department store padding prices to cover the damages of shoplifters.

Soderbergh's trying to stun us, to overwhelm us, to dump a load of information on us and get us to just talk about how absurd and complicated and impossible this thing that we're still fighting as a nation is. But he always knowingly undercuts the most heavy-handed of it; when one character goes off on a tirade against two DEA agents, one of them asks him if he thinks he's on "Larry King Live."

That's why a film like "Traffic" is so important. Movies with social or political agendas rarely accomplish much. Oliver Stone never got the files he demanded at the end of "JFK." "Fight Club" probably didn't dent Ikea's take. And people still smoke cigarettes and watch "60 Minutes" despite "The Insider."

But debates about the power of pop culture -- does it reflect or direct society? -- are better left to dorm rooms. These movies do spark national conversations, and if there's going to be any real change in American drug policy it's going to have to come from the bottom up. After many, many conversations -- when legalization, or at least decriminalization, becomes self-evident.

Some, like the folks at NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws), think that there's a major shift in the way we as a country think about drugs. They'll point to good signs, like Republican Gov. Gary Johnson in New Mexico, who favors legalizing marijuana and heroin, or medical marijuana referendums in California and Arizona. And now they can point to "Traffic." But realistically we're going to be rolling joints in the dark for a long time.

Most politicians still can't afford to look soft on drugs. In this year's presidential election, for example, only Ralph Nader and Libertarian Harry Browne broached the subject. Because of his didn't-inhale fiasco, Bill Clinton hadn't much to say on the subject until very recently, in the 11th hour of his presidency, when he suggested that we at least look at decriminalizing pot. And now we've got a president-elect with a similar problem: George W. Bush's "youthful indiscretions" and the Republican Party's law-and-order platform will likely keep any drug reform out of the executive branch.

But as the small documentary "Grass" pointed out this summer, it was middle-class families losing their children to prison who pushed Nixon to relax drug laws in the early '70s -- when some states decriminalized marijuana.

The real drug czar knows that a major part of the war on drugs is a war of images and messages. With the Partnership for a Drug Free America and the most sophisticated advertising agency in the world, it spends millions on advertising, inserting messages into television shows and magazines and even fighting popular referendums. "Traffic" is a cannon shot from the other side.

Shares