Baz Luhrmann's retro-modern musical "Moulin Rouge" is such a magnificent mess that it makes you feel hung over before it's even finished. It's like a shot of absinthe so strong you get the bedspins just from watching it pour over the sugar in the spoon. Normally, that wouldn't be a good thing. And yet just two days after seeing "Moulin Rouge," I can't help looking back fondly at the memory of it.

There's plenty I can't forget soon enough. The quick, choppy cutting makes the movie feel spit up in pieces instead of served as a whole. And the frenetic plot repeatedly grabs attention away from what should be the movie's central focus, the love story between Ewan McGregor's penniless writer Christian and Nicole Kidman's showgirl-courtesan Satine. Worse, Luhrmann's fondness for tight close-ups of the garishly painted showfolk of early 20th century Paris reduce them to Fellini leftovers.

But Luhrmann is a tricky director. I'm not sure how he does it, but his movies have a way of reshaping themselves in your memory after the fact -- it's as if they have viruses built into them that spring to life a day or so later, mysterious microorganisms that go to work in your brain to smooth out a movie's flaws and heighten its most sensual or exhilarating moments.

I know because the virus worked on me. When I first saw Luhrmann's 1996 "William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet" I perceived the movie as nothing short of a travesty, save for the performances of its two young leads, Leonardo DiCaprio and particularly Claire Danes. But a day or two later, I felt an inexplicable yearning to see the movie again, and the second time, I fell in love with it. I hate that movie's editing to this day; Luhrmann is clueless about how to organize his ideas, or even how to distinguish his good ideas from his terrible ones. That's without a doubt his major shortcoming as a filmmaker. But I found myself willing to weave a path around the movie's cracks and faults, led by Luhrmann's choice of (and use of) music, and by what I finally understood, the second time around, as his brave, honest and reckless heart.

"Moulin Rouge" is more ramshackle and harried than "Romeo + Juliet," and it doesn't have the same languorous resonance. The story, written by Luhrmann and Craig Pearce, is simple and desperately operatic. (It also, incidentally, has nothing to do with John Huston's earlier film of the same name.) "It was 1899, the summer of love ... " the voice-over begins, as young Christian (McGregor) relays the tale of how he came to Paris to become a writer, only to find himself entangled in a web of tragedy and loss.

Christian falls in with a bohemian crowd led by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (John Leguizamo, wonderful when Luhrmann remembers to tone down the dazzle around him), who introduces him to the redheaded dazzler Satine (Kidman), a showgirl at the Moulin Rouge, which is run by sozzled impresario Zidler (Jim Broadbent). Satine falls for Christian, but their love is doomed; she's practically been sold to the rich Duke of Monroth (Richard Roxburgh), a possessive, impossible tyrant. She is also, unbeknownst to Christian, withering away from consumption.

In pacing his movie, Luhrmann is like a hamster on a wheel, so desperate to keep our attention that he forgets to tell us where to look. He swings the camera around just when we need it to linger; he cuts away from details just when we're ready to drink them in. He never allows us to sink into the movie's romance, and that's a problem. The whole thing feels scattershot and dyslexic, a noisy clatter of letters on a page that fail to fall into a logical and recognizable order.

But I've already started to gather from "Moulin Rouge" a collection of details that I want to hang onto forever, things that I've rescued from the rubble of Luhrmann's passionate carelessness. Production designer Catherine Martin gives us a glittering nighttime Montmartre that's sprawling and alive. Its chief features are a magnificent, jewel-encrusted elephant that houses Satine's boudoir and a huge neon sign that glows through the night outside Christian's shabby garret. Luhrmann used the same sign in his terrific 1993 Australian Opera production of "La Bohème," where it substituted as moonlight for the characters' trysts. There, it spelled out simply "L'Amour" in flowing script. Here, it reads "L'Amour Fou," an advertisement for what's ahead as well as a warning.

"Mad" is a mild word for the overall mood of "Moulin Rouge." Its climax alone, an extravagant finale lifted straight out of Bollywood, a pageant of Easter-egg sari colors graced with a snow shower of red-and-white rose petals, achieves new heights of insane cinematic beauty. Other moments are less showy but just as spectacular: Satine and Christian, just beginning to fall in love, step out of a window to dance along the shimmering rooftops of Paris, while a smiling, singing moon right out of a Georges Méliès silent smiles down on them. (Its operatic voice is supplied by Alessandro Safina.)

There's been much written about Luhrmann's bravery in making a musical in this day and age, but I don't think he could make a movie that didn't have music as its heartbeat -- he's been making secret musicals all along. Even so, he takes a leap with "Moulin Rouge," and the gamble mostly pays off. The musical numbers range from extravagantly, gorgeously nuts (Satine's exhilarating opening scene, where she descends from the ceiling on a swing, purring "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend") to heart-joltingly touching and funny (Christian awkwardly wooing Satine with Elton John's "Your Song," at first reciting the words as if he's just pulling them off the top of his head). "Moulin Rouge" is a musical for the age of sampling, and yet it's oddly true to the spirit of the era in which it takes place. These characters, going about their business at the turn of the last century, find resonance in songs like "Heroes," "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and "Like a Virgin," without ever seeming stupidly anachronistic.

Some of the musical numbers blaze with unnecessary garishness. That would be less troublesome if it didn't detract from the work of the movie's two leads, whose mere presence is enough to fill the screen sufficiently. McGregor underplays his character's suffering -- he understands the distinction between melodrama and camp, in that the former can easily encompass nobility while the latter can only caricature it. His charm enfolds everything from the way he stammers when he's trying to open Satine to his love, to the suffering he holds like a noble vessel, chiefly in his eyes and in the roll of his shoulders, when tragedy sinks down upon him. McGregor's profound inner dignity always keeps him grounded; it also seems to be the underpinning to his appealing goofiness and humming sensuality.

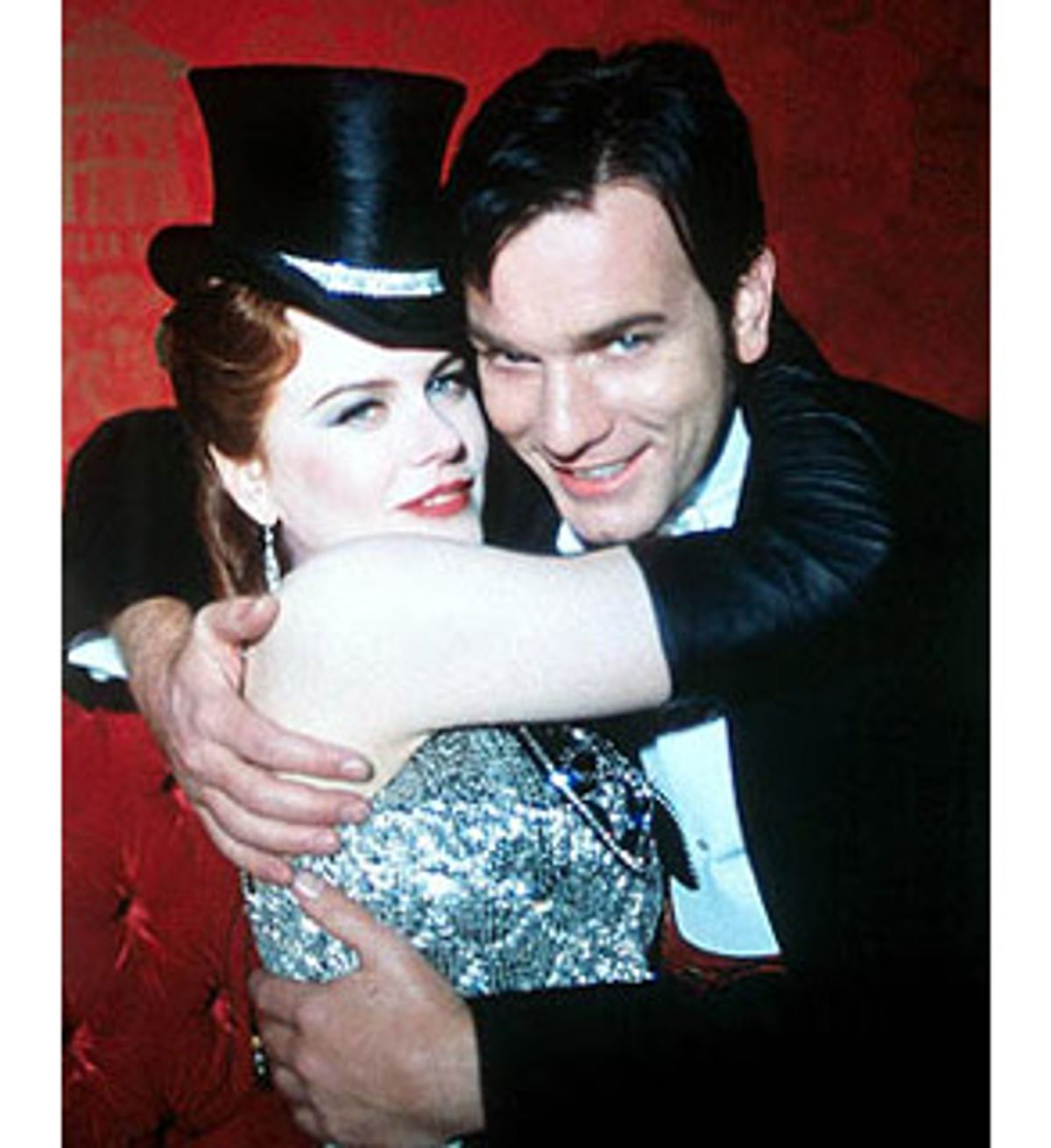

He lavishes both of those things, with tenderness and generosity, on his costar Kidman as Satine. Kidman has rarely looked so beautiful. Pale, luminous, cracklingly sexual and with a protective veneer that's both as hard and as delicate as an eggshell -- she's a cross between Rita Hayworth and a John Singer Sargent painting. When she's playing the showgirl, she cannily navigates the psychology of the biz with all its attendant bravado and feigned vulnerability: Her eyes look catlike and calculating, peeking out from behind those devilish Titian waves. But when she's playing the lover, the girl who's become enchanted by a handsome boy with no money, she's heartbreakingly girlish. Even her glamorous showgirl clothes seem to sit differently on her body. She makes a satin gown look like a tailored shirtwaist, a repository of warmth and womanly secrets.

That Kidman, McGregor and most of the other actors in "Moulin Rouge" do their own singing (mostly surprisingly well) is more than just a charming touch. It's an affirmation of the whole cast's commitment to Luhrmann's outlandish, go-for-broke vision: How far will you go to risk the audience's ridicule? And can you continue to believe in yourself, even if they laugh at you?

That vision, and the actors' pledge to it, is what makes "Moulin Rouge," messiness and all, so moving. Like a movie version of Mad King Ludwig's Bavarian fairytale castle, it's a mishmash of decoration, drapery and debauchery that's both deeply pleasurable and kitschy. It may not be the kind of place you'd actually want to live in. But after you've seen it, its rooms magically reassemble themselves in your memory, and the colors are softer, the vibe is warmer and there's love in every corner. "Moulin Rouge" is l'amour fou written in neon.

Shares