Brian De Palma's "Redacted" -- the title is a reference to the act of alteration, of editing or removing sensitive or confidential information -- is the messiest, most confounding picture about the Iraq war that has yet been made. It's also possibly the most direct, and the most potentially upsetting. "Redacted," a fictional story based on real events, wasn't even a germ of an idea when a representative of HDNet films asked De Palma if he'd be interested in shooting a film on high-definition video. De Palma was intrigued, but wanted to make sure he could first come up with an idea appropriate to the medium. He found his subject after he read about the rape and murder of a 14-year-old Iraqi girl, Abeer Qasim Hamza al-Janabi, in Mahmudiya in March 2006 -- an incident that recalled, to an eerie degree, the subject of De Palma's 1989 "Casualties of War," which was also based on a true story (recounted by Daniel Lang in a 1969 New Yorker piece).

To listen to a podcast of the interview, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

De Palma has said that essentially everything he has put into "Redacted" can be found on the Internet: The director trawled the Web, examining pictures, videos and journal entries made by soldiers, looking at Islamic fundamentalist Web sites and, perhaps most significantly, locating numerous photographs of Iraq war victims -- many of them children -- that would never show up in the mainstream press. "Redacted" consists largely of re-creations of the images, videos, testimonies and blog entries De Palma found on the Web. But with the exception of the very last image (a re-creation of al-Janabi's corpse), the photographs that close the movie are the real thing. In these pictures, some of which are graphic and all of which are disturbing, the eyes of the subjects have been blacked out -- in other words, the images themselves have been redacted. (Eamonn Bowles, president of Magnolia, the studio behind "Redacted," has claimed that the alterations were necessary for legal reasons because the subjects had not signed releases. De Palma has publicly decried the alteration of the pictures in interviews and at the movie's New York Film Festival press conference in October.)

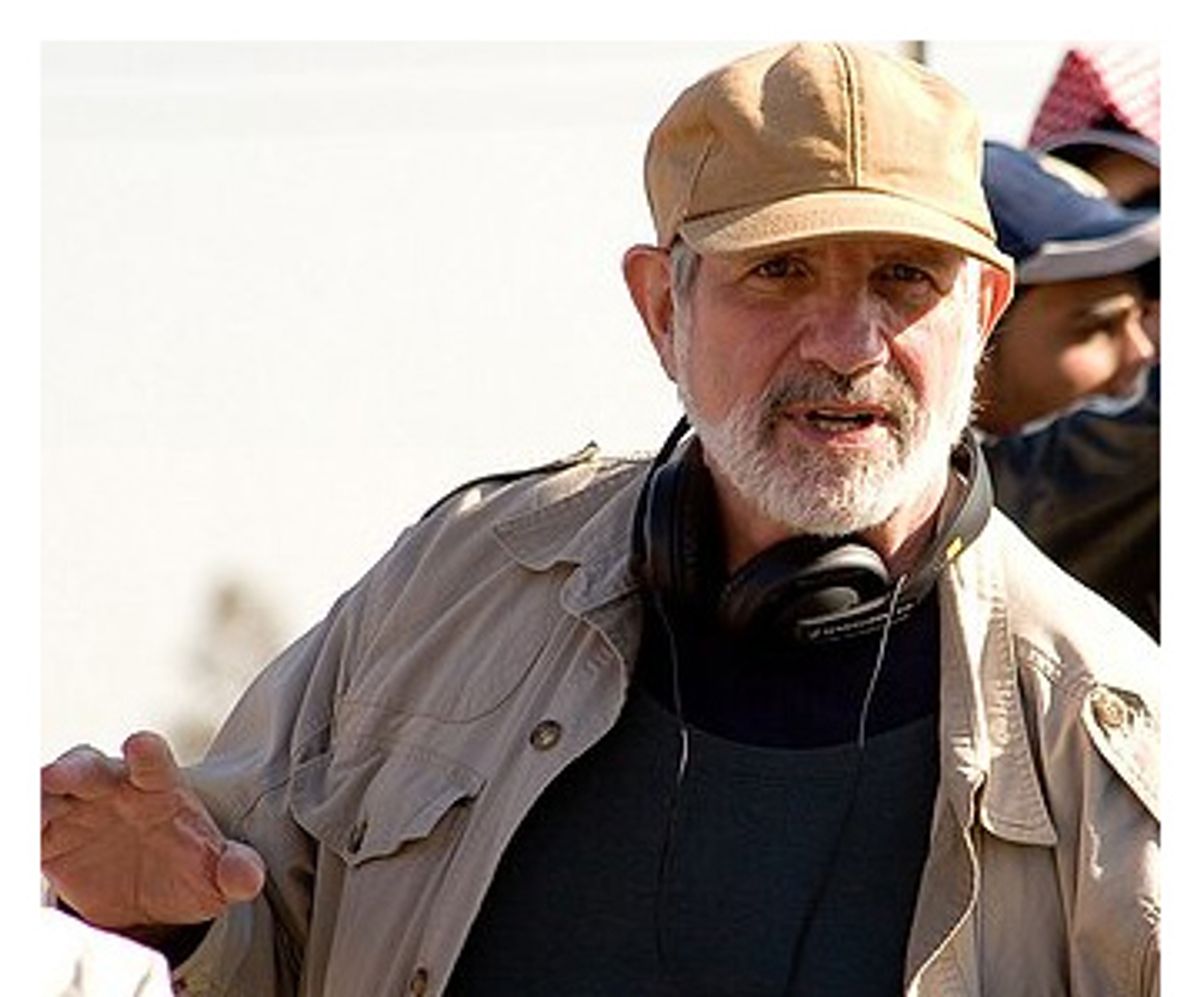

De Palma, 67, has built a career making movies that remind us we can't always trust what we see. With "Redacted," a very personal and very angry film, he goes even further in exploring our experience of what we see -- or don't see. I spoke with De Palma in October in New York, where he discussed the similarities between "Casualties" and "Redacted," talked about the failure of the media to tell us what's really happening in Iraq, and explained why he thinks Americans at home have been "living in the Green Zone." (To listen to a podcast of this interview, click here.)

As you know, because you've seen a lot of them, there have been all these Iraq documentaries: "No End in Sight," "Iraq in Fragments," "The War Tapes." And all the conscientious people on the left either have seen these movies or haven't and said that they have. It seems to me that you're trying to do something different with "Redacted," to get people to respond in a more immediate and emotional way.

Yeah, by the very nature of the drama. The great documentaries, like [Albert and David Maysles'] "Salesman" or "Grey Gardens," the ones I remember seeing in the '60s or '70s -- when documentaries have a real dramatic line, that can be devastating. But when you fictionalize things, obviously you can make connections that you can't make in documentaries. This [story] had all the beats that "Casualties of War" had. I mean, it was almost spookily similar.

That's part of what drew you to it.

That's exactly right. Plus, I think it's a great metaphor for these quagmire wars, where the guys get over there and they don't know why they're there. McCoy [one of the characters in "Redacted"] says, "You'd better have a very good reason to have your buddy die next to you." To go out and kill people, you've got to have a very good reason. When they get over there, it's like, "Why are we here?" And it's an environment they don't understand, a culture they don't understand. The people are not speaking a language they understand. They can't tell the insurgents from the al-Qaida, or whatever sect they're fighting. And they band together -- that's the only thing they can hang onto -- and then one of their buddies gets blown up or shot. And they take all their anger and frustration out on the people.

My understanding is that you'd read or were aware of the Daniel Lang piece that ran in the New Yorker in 1969, the one that "Casualties of War" was based on.

I read it when it came out in the New Yorker. I tried to get ahold of that property for years!

And it took a good 20 years for the movie to get made.

Because nobody wants to make movies like that. They're impossible to get made. Even [when we were] closer to the Vietnam War. And of course, with the success of "Platoon" -- well, it was decided that maybe these war movies make money. And that's when we got our movie made.

And we know what happened then: People just didn't go out to see it. Maybe one explanation is that people weren't ready to see it.

I just think these are difficult movies to get made, and they're difficult movies to market, especially when they have such serious themes and they're kind of upsetting. "Coming Home" was a successful movie. They're never like Spielberg/Lucas successes, but they do OK. But they're always hard to get made. And it's usually because of the particular craft and the artistry of the movie that somehow gets it past that [attitude among audiences of], "You know, why do I want to see a depressing movie about the war?"

Do you think people are ready for "Redacted"?

[Pause] I don't know, to tell you the truth. It was made so inexpensively, and was made because of a certain sequence of events that happened, having to do with HDNet coming to me and [asking if I'd like to] make a movie for $5 million, in high definition, and reading about the incident and knowing these Canadian producers, and going on the Internet and finding all these unique methods of [telling the story]. All that came together very quickly, so the whole thing flowed. I never thought -- I don't think Oliver [Stone] thought, when he made "Platoon," that it was going to be a big success. You just make a movie you feel very strongly about. And it's made so inexpensively that you know it will pay for itself.

I also think the immediacy of the movie alone is effective. The story is based on relatively recent history; it's something people are thinking about, or should be thinking about.

It happened a year ago. But people aren't really thinking about it. I think they've basically forgotten about it. But what's so striking about it, and what gets such a reaction -- unlike in Vietnam, where we saw stuff on television and in our magazines -- is that nobody's seen anything [like that before]. I think that's why people are so stunned by the pictures at the end. They haven't seen pictures like that -- even though they're all over the Internet.

There have been some very angry responses to the movie, people saying, "Why are you putting this in front of me?" I hate to be ageist, but I was a little girl during most of the Vietnam War, and I remember seeing some pretty rough things on television, and in Life magazine. Those things were out there. You didn't have to seek them out. So I wonder if people feel a little assaulted by what they see in "Redacted." I'm not saying that's your intent.

I think it's because they've been living in the Green Zone. They've been sheltered from this war. That's what the architects, who are my age, learned from Vietnam: Don't show any pictures. Get a volunteer army. Don't let the populace turn against you. And that's what they did. They did it artfully, and that's what I was watching year after year on television. Embedded reporters? What's that?

And they're still getting killed. Being embedded doesn't offer them much protection.

It's a propaganda machine. And obviously they'll tell sympathetic stories about the soldiers they're with because the soldiers are protecting them and they feel very heartfelt things about them. And they're not going to take pictures of anything the soldiers are doing that's going to make them look bad. But that's not what they're supposed to do. They're reporters.

I want to talk about "Casualties" a little bit more. One of the problems that it faced when it was released was that there was a trend in feminist discourse toward looking at movies through a certain ideology. If you strayed from that, you weren't part of the club. Someone I knew at the time made the argument that "Casualties" wasn't valid because it was about a rape but wasn't told from the woman's point of view -- which seems to me a very limited way of looking at the world.

I'm trying to think of movies [about rape] that have been told from the woman's point of view. There was one filmmaker who made a movie about her rape, about 25 years ago. But go ahead.

It strikes me that over and over again in your work, you've dealt with the horrors that men are capable of. And even if you're not talking strictly about sexual victimization, you're often dealing with the ways men fail women. Do you think that obsession with gender issues can get in the way of being a humanist?

[Laughs; laughs some more] What a question! Whoa. [Pause] Say that again?

Can obsession with gender issues get in the way of being of a humanist?

I think the mistake you might make, or a critic might make when they look at somebody's work, is that you're looking for some kind of design that isn't there to make it fit into some kind of framework. I remember an interview with Bergman once, when somebody was asking him [about "The Seventh Seal"], Why did he have those guys on the horizon, dancing with death? And where was Edmund, or one of the other characters? Why was he not included? And Bergman said, "Well, he was sick that day."

In this case, I have to show you my process and then you can make whatever analysis you're going to make. Obviously, in "Casualties of War," as in "Redacted," you're dealing with the rape of a country. So when you have the actual rape of a girl, you're making a big metaphorical [statement] -- this country is being raped, it's being destroyed. And there's nothing left but ashes and sobbing faces. And you see this incredible military machine, clunking around; it's very masculine: "Bomb it! Destroy it! We'll sort out the good from the bad from the bodies." You fall into those kind of gender identifications, but that's why I was attracted to this particular story. I don't look upon it as, What kind of feminist politics are involved here? I'm just seeing this innocence being destroyed. This is how I look at this war. And I wonder how did I, an American, get to that place? That's what I'm trying to examine in these characters.

Shares