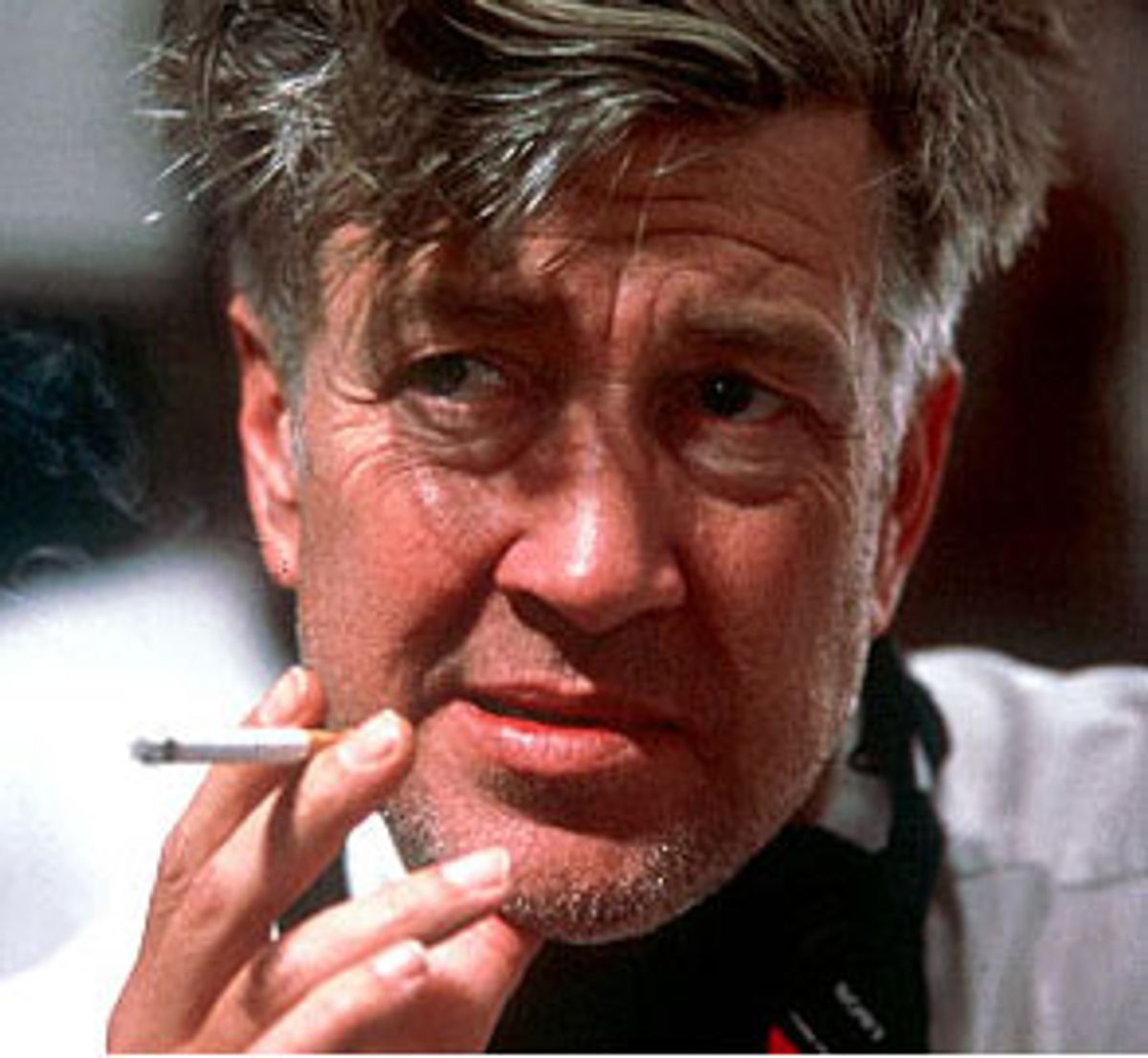

After the change of pace of 1999's "relatively" normal "The Straight Story" -- a G-rated film released by Disney -- director David Lynch is up to his old tricks again with "Mulholland Drive," a film that is likely to satisfy and provoke his fans, while irritating and provoking those who don't respond to his particular brand of skewed reality.

When Lynch made his feature debut with "Eraserhead" in 1977, it seemed clear that he wasn't destined for a Hollywood career. An extraordinarily weird exercise in surrealism, "Eraserhead" demonstrated amazing technical control, a bizarre but undeniable sense of humor and (most of all) a dazzling visual style, all in the service of a horrifying dreamlike narrative that made little traditional sense (unless your notion of tradition is Dali and Buñuel). One would have guessed that Lynch would spend the rest of his life putting his dreams and nightmares up on the screen in little, low-budget, personal films.

But Mel Brooks had the inspiration to hire the director to helm the version of "The Elephant Man" he was producing -- leading to a best director Oscar nomination for Lynch and thus Tinseltown credibility. The result has been one of the strangest bodies of work ever to emerge from the American film industry. A big-budget adaptation of Frank Herbert's sci-fi perennial "Dune" was a catastrophe that almost threw Lynch back into midnight shows at art houses; but the deal he cut with "Dune" producer Dino De Laurentiis allowed him to make the sensational and disturbing "Blue Velvet," a perfect blend of his distinctive style and concerns with traditional Hollywood genre conventions. "Blue Velvet" -- which ended up near the top of any and all polls of the great films of the '80s -- led to "Twin Peaks," the TV show that (briefly) made Lynch a household word.

The "Twin Peaks" phenomenon was a roller-coaster ride that took the show from national obsession to old news within about eight months. For a brief time, Lynch seemed to be on the cover of every national magazine, and analytical speculations about where the show was going appeared in quarters where analysis had rarely been seen before; but, as soon as the murder mystery at the center of the plot was "solved," the show tumbled downward in both the ratings and in critical opinion.

Since then, the director has done other TV shows and directed the Cannes palm d'or winner "Wild at Heart," as well as "Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me" (a sort of prequel to the series) and the radical puzzle movie "Lost Highway." While his feature projects have been distressingly few, he has kept himself more than busy with his still photography and artwork, his comic strip "The Angriest Dog in the World," producing record albums, and now with an ambitious Web site, which he hopes will be ready any day now.

"The Straight Story," his last feature, was surprising only in how "unsurprising" it was: that is, it was by far his most conventional project, the true story of Alvin Straight, an old man who rode a lawn mower a few hundred miles to visit his ill and estranged brother. It had Lynch's stamp if you looked close enough, but it represented another unexpected career turn.

"Mulholland Drive," on the other hand, "feels" like Lynch, most particularly like "Twin Peaks," transported from the spooky woods of Washington state to the spooky world of Hollywood. It's hard to describe the plot without destroying the film's pleasures, but suffice it to say that it centers around two women: Betty (Naomi Watts), an apparently naive, starry-eyed blond, who, in the tradition of a million small-town girls before her, has come to Hollywood to be a star, and "Rita" (Laura Elena Harring), a dark-haired beauty, who has lost her memory after a car wreck on Mulholland Drive. As the two of them attempt to reconstruct Rita's past, their lives intertwine with a bunch of other L.A. players: some inept hit men, a temperamental Hollywood director whose ability to deal with executives is no better than his ability to deal with his marriage, a mystically withdrawn studio boss and a scary guy in a cowboy hat.

"Mulholland Drive" may seem like a reflexive response in the opposite direction after the experience of making "The Straight Story," but in fact it was in development around the same time as "The Straight Story" and was shot shortly thereafter. Its genesis is unique for a major studio release: The current version is a two-hour, 27-minute retooling of a script originally shot as a 94-minute pilot for a TV series; ABC, which had approved the script, chose not even to air the pilot once it was done, despite Lynch's efforts to cut the project to their liking.

It was a strange and frustrating decision: It seemed as though they made a deal with Lynch and were then shocked -- shocked -- when he turned out something weird. What did they expect from a man who has been called (among other things) the Wizard of Weird, the Sultan of Surrealism and the Boy Next Door (from Mars)?

So a feature-length work by one of America's premier directors was left in a legal limbo: ABC owned it, but didn't want to show it.

"I was so happy with the cast and all the people involved with that show," Lynch said when I spoke to him by phone recently. "It was so much fun, I can't tell you. But they weren't behind that, not one little bit. It could have had a life, and people might have enjoyed it."

Of course, what had Lynch himself expected? After "Twin Peaks" crashed and burned, ABC had also ordered up (and then rapidly abandoned) "On the Air," an intensely strange sitcom.

I ask Lynch why, given these experiences, he would ever want to work in TV again. Hadn't he learned his lesson? "You do learn from your past, but sometimes it's like, you're a dog, and you love chocolate, and you get sick from chocolate, but you're going down the street, and you smell that chocolate shop, you're gonna go in there again. And then you don't think about the painful side of the past. You just get kinda euphoric about going there again.

"I mean, I'm a sucker for a continuing story. That's one of my problems. And that's why I wanted to do it as a series. I had no frustrations with it until ABC saw the pilot and hated it and in a sense killed it."

I tried to get him to snap at ABC, but he wouldn't take the bait. "Looking back," he said, "I see that they did me a huge favor. Number one, by allowing it to get going as an open-ended pilot. And number two by killing it. Then we were at a very strange place, because we had this open-ended pilot and a desire to turn it into a feature. But my friend Pierre Edelman of Canal Plus [the French production company] saw the pilot, saw the possibilities, knew of my desire to turn it into a feature and got Canal Plus to work over the next year to get the rights.

The buyout gave Lynch the wherewithal to turn the pilot into a feature, and apparently allowed him to put the original story into one of his "Lost Highway"-like puzzle boxes. "I was very fortunate," he said. "I sat down one night, and these ideas came into me, showing me how to do it. Up until that point, I didn't know what I was gonna do. And so the ideas that came in were only possible because it had started open-ended. It's strange how what went before was so necessary to the final form. And I don't think it would have been the same at all if it had started out being a feature. So it's an interesting trick of the mind."

So in the long run, is he basically happy that the show didn't get picked up?

"Oh," he said, in his most endearing Jimmy Stewart stammer. "I'm ... I'm ... I'm ... next door to euphoric!"

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Lynch had engaged in a similar process on "Twin Peaks": For a European theatrical release, he added extra footage to the American broadcast pilot to "wrap up" the mystery. (Curiously, in America, the European version is available on video. But in Taiwan, you can buy the American version. Go figure.) He eventually recycled some of that material for the series, most notoriously the first of the "Red Room" sequences, with the dancing dwarf and the backward-sounding dialogue.

Lynch said: "One of the greatest experiences of my life was getting the idea for the Red Room and what that led to finally. So you never know where ideas are going to lead."

I ask him to compare that to the even stranger retrofitting process on "Mulholland Drive": More than a year after finishing the original pilot, he reassembled the cast and shot an additional 45 minutes or so of footage, designed to change the open-ended pilot into a complete work. I tell him I've glanced at a version of the original script that's floating around the Internet; this gave the impression that the first hour and a half or so of the film is pretty much the pilot, with all the new footage at the end.

"No," he says. "That's not right. What is interesting is that the ideas that came in affected the beginning and the middle and the end. What happened was that what had gone before was suddenly seen from a different angle. Many things went out, and a bunch of new things came in, which affected what had gone before, because of the new angle. And then the new footage fit in, at the beginning and the middle and the end. It was like a brand new ballgame, but the ballgame was built on what went before.

"It was great, because, you know, you don't know for sure if you're going to catch these ideas, and there was a period that was sort of filled with anxiety before they came in, because here's this company that's bought the rights and spent a lot of money, and I didn't have the ideas yet."

While he's loosened up a bit in recent years about discussing his work, Lynch has a reputation for refusing to elaborate on intentions or the creative process beyond the evidence on the screen. (The single most emphatic reaction in our conversation came when I asked about rumors he was doing a commentary track for the upcoming DVD release of the first season of "Twin Peaks": ""No! I don't believe in commentaries.")

Nonetheless, I push for more specifics about the different versions of the project -- unsuccessfully. "Let me tell ya, Andy," he said. "First of all, I only go by, you know, what I feel, and when I go see a film I want to know next door to nothing: I just wanna go in and have a pure experience and have it be my own experience. And it doesn't really matter how a film gets to be the way it is in its final form. It's interesting maybe, looking back, or a couple of years down the line. But whatever overlay you put on a film that an audience takes into the theater can putrefy the experience and cause so much trouble.

"The beautiful thing is that in pretty nearly every film, I think, when you're writing, an idea will come that deals with the ending, maybe even before an idea that deals with the middle. So how the ideas come in doesn't really matter. It'd be nice if they came in fully formed, but they don't. But it doesn't make any difference if they finally form together into a story that you love enough to translate to film."

In other words: Back off!

In the phone conversation, I gave it one more shot, asking about a few specific scenes that struck me as, well, too daring in their explicitness to have been conceived for television -- things that I couldn't picture ever being allowed on the Disney-owned ABC.

"Well, I don't know what to say about that, because I don't want to introduce certain thinking into people's minds."

I'm about to give up and move on, when Lynch shows some mercy: "But I would say that there are a lot of different ways to skin a cat. And in television you can imply things; you can do much more than you think. You just have to do it a hair differently. I found out in 'Twin Peaks' that a lot of the restrictions in television led to some very interesting things that were even better. You know: Your mind goes to work to solve a certain problem, and, because of this need, sometimes the solution is pretty interesting.

"Sometimes the restrictions are great. And sometimes no restrictions is great. You know, we each draw a line somewhere, and the line is different within each of us. And there are certain lines you don't cross over."

While "Mulholland Drive" is in no way a retread, the peculiar blend of deep creepiness and offbeat humor is most reminiscent of the tone in "Twin Peaks." (If "Twin Peaks" was "The Hardy Boys Go to Hell," then "Mulholland Drive" is "Nancy Drew in La-La Land.") And Lynch aficionados will recognize, not merely familiar themes and moods, but even specific scenes that invoke the earlier show, as well as "Eraserhead" and "Fire Walk With Me". Most of all, there is a major plot element -- which it would be churlish to mention -- that calls to mind Lynch's 1997 "Lost Highway," one of his best and least commercially successful films, and certainly the strangest since his debut with the utterly singular "Eraserhead."

In "Lost Highway," the protagonist, jazz musician Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), is in jail for the alleged murder of his wife (Patricia Arquette). He has no memory of killing her and claims he's innocent; and we -- being locked to his point of view -- haven't seen the murder either.

Then one morning the guards arrive to find that Fred isn't there -- or, more exactly, that he's turned into (or, in some utterly inexplicable way, been replaced by) someone else entirely -- a young and callow auto mechanic named Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty). Of course, the authorities have to let him go. He leaves and gets involved with a mobster with a sexy moll, played by ... Patricia Arquette. Then things get weird.

It's an insane concept, one that doesn't vaguely map onto the real world and has very few precedents in cinema, yet -- even more unbelievably -- "Lost Highway" was one of two films that year to use the idea. I ask Lynch if he'd seen Steven Soderbergh's wacky, low-budget "Schizopolis," which came out within a few months of "Lost Highway."

"Yeah! A whole different take on the same thing!" he laughs. I wonder about the coincidence. Was there something in the air ... ?

"It's O.J. Simpson, Andy."

"What?"

"That's what did it," he says. "Think about it: I wasn't really aware of it at the time, but it must have been inspired by, subconsciously anyway, the O.J. Simpson trial. And how O.J. Simpson's mind had to be tricked, so that he could go out and play golf, rather than commit suicide for the deed he did."

I think about asking Lynch if he has a similar key to "Mulholland Drive," but it's become clear that, if he does, he's not revealing it. At least not now.

Shares