Eye-scanning spider robots, vomit-inducing "sick sticks," holographic home video cameras, vertical highways: Welcome to the United States circa 2054. Steven Spielberg's "Minority Report" is essentially a neo noir in which Tom Cruise runs around trying to prove his own innocence. But what distinguishes the film -- besides its ominous political warning -- is its dense, ingenious conception of what life will look like 50 years from now. Not since the neon-soaked "Blade Runner" (like "Minority Report," also based on a Philip K. Dick story) has such a conceivable, self-contained and ultimately disconcerting vision of the future been captured on-screen.

That the film succeeds is as much a credit to Spielberg's direction and Cruise's sturdy performance as it is to Alex McDowell's inspired production design. Helping McDowell achieve the look and ideas of the film were a coterie of self-styled futurists assembled by Spielberg prior to filming. This "think tank summit" (as it's been widely dubbed) hosted a cross section of philosophers, scientists and artists. Two of these conceptual consultants, Harald Belker and John Underkoffler, spoke with Salon by phone from their respective offices in California.

A native of Germany, Harald Belker is recognized as one of the premier conceptual artists/designers in the business. After graduating from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., Belker designed automobiles for Porsche and Mercedes (most notably the latter's Smart Car). In 1996, in his first Hollywood job, he was asked to dream up a new Batmobile for the franchise-killing "Batman and Robin," and went on to work on "Inspector Gadget" and "Armageddon."

John Underkoffler, of the left-brained variety, spent the better part of his pre-Hollywood years as a researcher at MIT's prestigious, multidisciplinary Media Lab. There, he toiled on a myriad of intellectually minded projects encompassing everything from holography to computer graphics to electronic publishing. Having survived his virgin foray into the film industry with "Minority Report," Underkoffler now finds himself a wanted man, serving as a science and technology consultant on Ang Lee's anticipated comic-book opus "The Hulk."

What exactly is a "futurist" and how do you become one?

Harald Belker: I know people who call themselves that, but I'm not one of them. [Laughs.] I think I live in that world, sort of thinking of the future a lot. I like to give my input toward futuristic looks and designs specifically. But call myself a futurist ... I don't think so.

John Underkoffler: I think you just have to blather a lot about the future. I hope to see the term become slightly debauched -- in the present it probably already is. It was still a plausible position, say, three years ago, because the economy was good and we had the kind of technological utopianism thing going on. But it doesn't work as well when everyone has told all the stories there are to tell and actually it's time to invent some of the stuff instead of just talking about it.

So, technically, would it be fair to say that you get paid to see what the future is going to be like?

Underkoffler: In the context of these movies, that's definitely a piece of the job. The interesting thing is that it's not just broad-strokes prognostication. It requires coming up with all the details as well.

On "Minority Report," you're credited as being a "science and technology advisor." What does that mean?

Underkoffler: It extended quite broadly. It was everything from inventing future history, sort of extrapolating from the present to describe trends that by 2054 were already in the past and would've led to what we see on the screen. And these aren't merely technological trends but also social and political. For everything you see on the screen, there's actually a hundred times more well-knit back story.

Describe the process of how you begin to invent an imaginary world. What's your source of inspiration?

Underkoffler: I think it might even be more interesting to talk about the collective effort inspiration. For example, Alex McDowell produced -- and kept revising throughout the course of preproduction -- what we called "the 2054 bible." It's a brilliant document, and I hope someone gets encouraged to publish it. Its notion was that it kind of laid out in about 80 pages or so the entire world that we were going to build. It covered everything from architectural overviews, the trends that had led to more vertical buildings and cities, the urban areas pulling in the skirts, so to speak, and rising into the air to allow green to return to surrounding lands (that sort of ecological imperative), the political tenor of the times, the individual economics of different social strata that led to certain architectural forms, right on down to the gadgets -- the nonlethal weapons, the hover packs, the little spider robots that run around and identify you.

Had you read Philip K. Dick's story before you started working on the film?

Belker: They gave us the short story to read when we first got started because the actual script was all secret. So we'd get a page or so which we were directly involved with. I got pages where vehicles were described. The short story stuff was promising, though it didn't go into much detail.

Underkoffler: Oh yes, long before. I'm a huge fan of all of Dick's writings. It's a very compact little piece with a fascinating central idea that very much competes with all his other stuff. As with the rest of his writings, he recognizes that social science fiction is more interesting than pure science fiction. He was one of the few guys back in the '50s who knew the truth about technology. Everyone else wanted shiny ray guns and perfect societies floating around in anti-gravity space stations and who knows what. Dick knew that technology mostly doesn't work or complicates things in unforeseen ways. And so, in Dick's books and stories, you always have doors that won't let you through 'cause you have to give them a quarter and you have to argue with them because you don't have any spare change. In general, with him, it's the intersection of high-end science with other more human elements: individual psychologies, larger-scale sociology or politics. That's what makes him continue to be relevant where other authors of the same era ... their shiny spaceships and ray guns look a little tarnished right now.

How often did you refer to the original text? Did you have much creative license?

Belker: I don't think I had much license except for the actual design of a vehicle. I'm definitely bound by the direction of the director and the production design, but the way it looks is my problem.

Underkoffler: I myself didn't, and I think that the film took everything it was possible to take from the story. By the time we were up and running, those ideas were so fully dissolved into the fabric of everything that we were doing, it wasn't as if had to go back and look at the scripture, so to speak.

What were some of the ideas or concepts you personally devised that made it into the final film?

Underkoffler: The sort of single largest scale item was the gestural interface language that we see in the first scene that Mr. Cruise's character uses to sift through the pre-visions -- the evidence dreamed by the pre-cogs. We had him in the middle of that giant curved, transparent screen and Steven's brief was that he wanted the interface of that computer to be like conducting an orchestra. Armed with that brief, I went off and devised this whole kind of sign language for interacting with this computer, for controlling the flow of all this information. That was great fun and it derived in some ways from my earlier research back at MIT.

Much has been made of this "think tank summit" hosted by Steven Spielberg prior to shooting. Can you give us an idea what that experience was like?

Belker: I thought, "What is all this?" [Laughs.] They went into great detail on medical future, architectural future, the rising of the sea level. For me, what was most interesting was the way they foresaw the future; if you really showed that in a movie today it would be unbelievable. So, to make it more realistic, you almost have to draw back from that and show it a little more reasonable.

Science used to draw on sci-fi all the time, but that relationship has changed: now sci-fi draws more from science. Which does this film do?

Underkoffler: I'm not sure that I totally agree. I think in some ways, science draws more than ever from science fiction. Here's one example. We had the constant problem of designing access panels to high-tech installations, stuff that appears in movies where you scan your thumb or your iris. And what does it say when you can't get it? It says, "Access Denied." Everyone knows that. The guys who have to build that hate "Access Denied" -- we all hate "Access Denied." It's such a clichi, but the fact is, the people who build those things for real make them say "Access Denied." And why? Because we all know that from movies.

Of all the technological advancements showcased in the film, how much of this stuff actually exists or is in the early stages of development?

Underkoffler: I would say a surprisingly large fraction. Almost an astoundingly large fraction. The mag-lev cars, for example. Although we don't have mag-lev technology that works on vertical surfaces, mag-lev technology has been around for many decades, spearheaded by professor Eric Laithwaite, who died not too long ago. And, of course, in Japan and Europe you have mag-lev trains. The nonlethal weapons are all variants or extrapolations of currently existing or under-development technology. It would be hard to identify anything that had no grounding in reality. I think that was very much by design.

Are there any concepts to which you were particularly attached that never made it into the movie?

Underkoffler: [mock coyness] Mmm ... not sure if I'm allowed to say such things. I mean, there was a lot we certainly didn't have time to do. We had a couple of interesting gadgets. Stuff like media-bots that were kind of autonomous, flying robots that would collect video and audio footage of the scene of the crime, a sporting event, some other paparazzi-intensive place. And they'd sort of jostle with each other for space and transmit it back to TV. The world that we all had in our heads was complete and as rich as our real world.

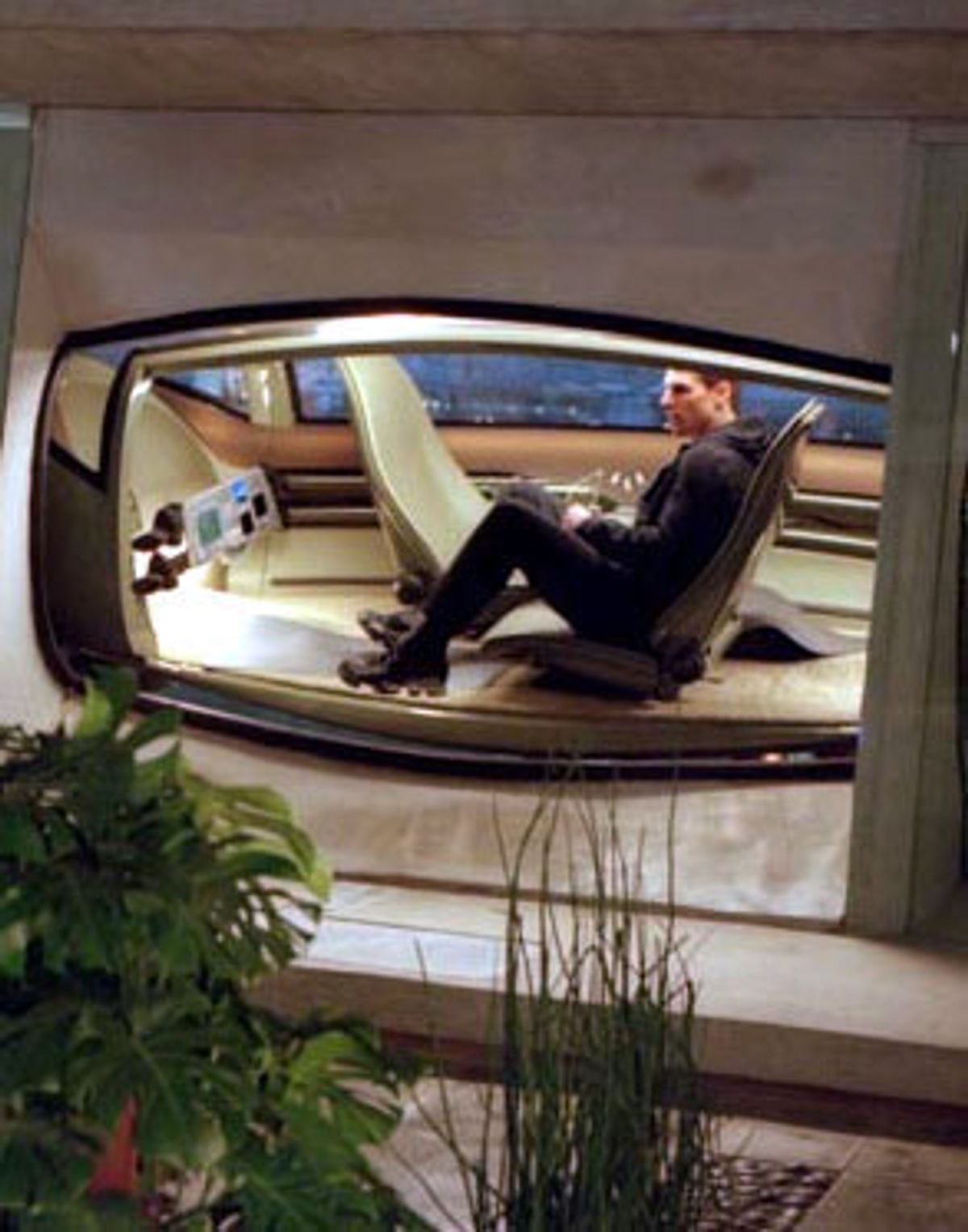

Belker: Yeah, I wish there were a lot more establishing shots of the transportation system, not just a quick drive-by. [Laughs.] There was a lot of work done on explaining how the hovership works, the whole transportation system. It was fantastically put together and yet you see very little of that. But, the way he [Spielberg] was shooting the film, the subject matter and the actor were his prime goals.

As a futurist, do you see the world as you think it will be or as you personally want it to be?

Underkoffler: The more time you spend thinking about that sort of thing, the more you have to acknowledge how things rarely turn out the way you intend. Very often it's the case that new technology -- even with beneficial ends in mind -- turns out to have effects you didn't expect at all. I think more and more I feel wary about technology just in the sense that we're rushing headlong into any number of different of technologically advanced fields without a full understanding of what's necessarily going on. Bioengineering is an obvious example -- just hanging around waiting for the mini bio-apocalypse.

The sci-fi genre often has a tendency to cannibalize itself -- almost to the point of parody. This film, however, boasts a look that is a lot fresher and more original than most. If you could put your finger on it, how did you manage to accomplish that?

Belker: For once, they tried to show a very positive future environment. I mean, we all lived through the bible of all sci-fi movies, "Blade Runner," which painted a very dark view of the future. And many, many sci-fi films after that kind of reflected what "Blade Runner" had started. So, there was a conscious effort to go the other way, to make it a positive, bright future where we solve a lot of problems and make life more pleasant.

But there is a lot of negative as well. Of all the fantastical inventions featured in the film, which do you fear the most?

Belker: Those little spiders. You have to surrender. Watching the "First Look" special on HBO, I think one of the guys said, "You don't have 15 minutes of fame, you have 15 minutes of privacy." If that is all taken away, that's a pretty scary thing.

Underkoffler: I think the clearest warning comes in relation to the kind of Orwellian or Huxley-esque scenario, where your eyes are constantly being scanned, your identity is being assessed at every moment and your location known at all times. In the movie, of course, that's motivated by principally market concerns, commercial concerns. The idea is that if we can identify you at this place and time, then we can advertise very specific to you. "It's time for a Guinness, John Anderton." [Laughs]

How much input did you have in the whole advertising scenario?

Underkoffler: That idea was integral from the very beginning in Steven and Alex's conception. The idea that your privacy was really a thing of the past, that the pure market forces had long since eroded everyone's intimate civil liberties to the point where only the wealthy could afford to not be bothered all the time. That was one of the benefits of extreme wealth, that you could afford to silence some states where stuff wouldn't be yammering at you constantly trying to sell you watches and beer.

Is this film more of a cautionary idea or does it present more of an inevitable future?

Underkoffler: I think it's something that is in danger of happening right now. I mean, given the awful events of last fall where we're starting to see a lot of this stuff on the immediate horizon. We have video surveillance systems being installed in Boston's Logan Airport and Providence Airport that are being tied on the back end to template matching -- facial recognition systems. They may not be accurate enough, but we're at that moment where if we, as an ostensibly democratic society, don't make some choices, the choice will just happen automatically.

I think we are in danger of approaching the world shot in the film from the opposite standpoint. In the film, we see a society with this universal surveillance because advertisers benefit from that, and they sort of pass off the information to peacekeeping forces and law-enforcement agencies like "Pre-crime." I think we're in danger of doing that the opposite way around, where people's knee-jerk reaction concerns for national and personal security allow that kind of surveillance to take hold. And then, of course, there's nothing to stop stuff from migrating into the commercial sector. If everyone's being scanned and identified all the time anyway, maybe the government would like to make a few extra bucks selling it to Timex or whoever wants the demographic information.

Do you see this type of future as unavoidable or can society do something to prevent this so-called progress?

Underkoffler: Well, the most important thing is for people to remain really aware of what's going on and, having made a decision about it, to speak that decision clearly. Which isn't necessarily something always in practice.

Belker: How many phone calls do you get everyday of people advertising? Isn't that annoying already? I wish I could turn that off. I mean, with the Internet today and your personal information available everywhere, we hope that doesn't go out of control.

In your opinion, what is the most unlikely thing to happen in the future that we see in "Minority Report"?

Underkoffler: Clearly the farthest out element of the story are the pre-cogs themselves, the essentially psychic adolescents who float in the tank. That was our largest leap. The whole movie is predicated on the accidental creation or discovery of these psychic kids.

Belker: The hover packs.

Which scares you more: The world depicted in "Minority Report" or the one we live in now?

Belker: Really neither. I just see technology exploding in the future. If you look at the last industrial revolution, what humankind has done in the last 50 years -- there has to come some good from that.

Underkoffler: Well, because the one depicted in "Minority Report" is fictional, we always have the option of correcting it through rewriting. The one we live in now is ultimately more frightening because there's no promise that we can divert the course, even if we were vigilant enough to watch the course and see where we're going and try to change it. There's much more uncertainty in the real world.

Shares