Each year, the Academy Award nominations bring at least a few surprises: Maybe a certain superstar actor or actress doesn't get the nomination everybody expected, or a previously unheralded writer or director sneaks into the pool of nominees. But this year in particular a crop of truly fresh-faced contenders from foreign and independent cinema have gained entrance to Hollywood's premier bash. And some of the most interesting names gracing the Oscar ballot are ones most moviegoers don't even know at all.

Keisha Castle-Hughes of the art-house favorite "Whale Rider," for example, is at 13 the youngest best-actress nominee ever. And Castle-Hughes is joined in her category by Shohreh Aghdashloo, the heretofore all but unknown actress in "House of Sand and Fog," as well as by Patricia Clarkson, whose role in "Pieces of April" comes after she starred in seemingly every film to be entered last year at Sundance.

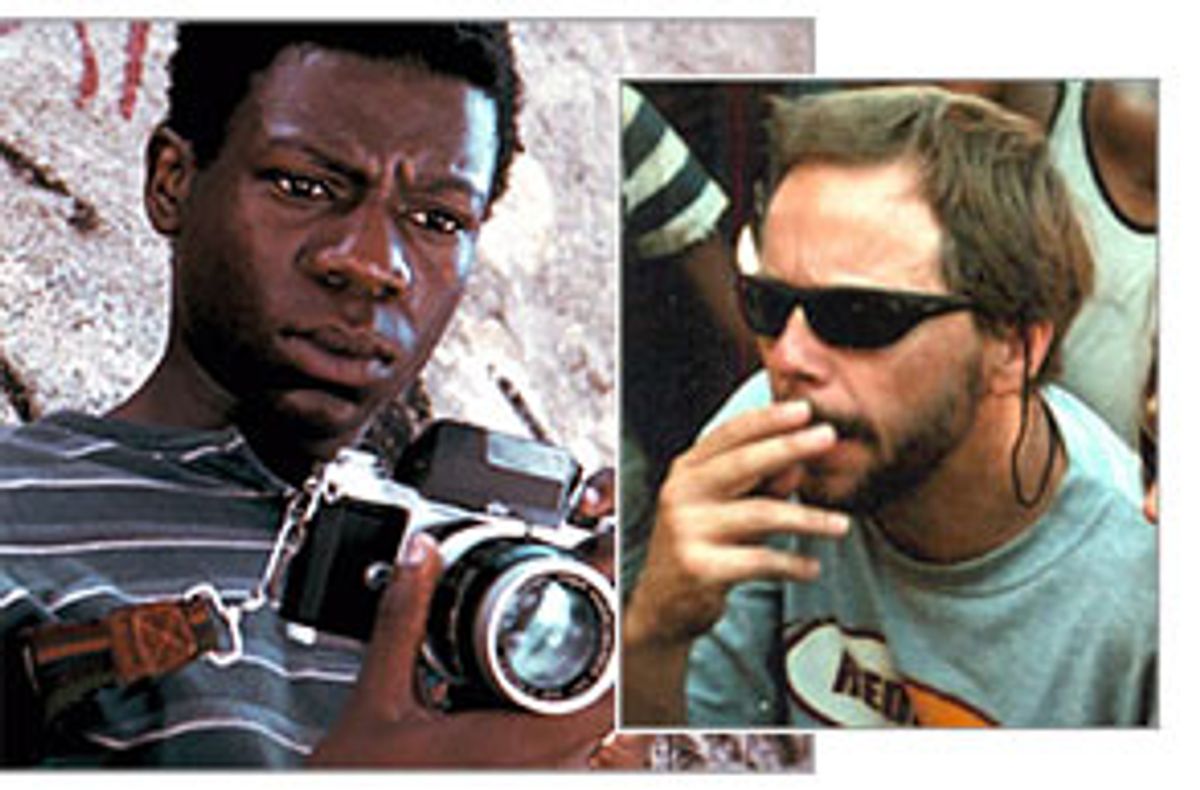

Meanwhile, a little-seen but critically acclaimed picture from Brazil, "City of God," has earned three major nominations: for best director, best cinematography and best screenplay (Adaptation). Although it's worth noting that "City of God" has been distributed by Miramax, easily the most successful studio when it comes to guiding (some might say "bullying") its films to Oscar success, it remains outright astonishing that a foreign film that doesn't pander to its audience with sappy feel-good moments can register this resoundingly with the notoriously conservative academy, which also can be pretty lazy when it comes to seeking out obscure films en masse. If you'd predicted before Tuesday's nominations that "City of God" would be more honored by Oscar than, say, a studio epic like "Cold Mountain," you'd have been laughed out of the room.

In the hours just after Oscar nominations were announced, Salon spoke with "City of God" director Fernando Meirelles, who has already garnered comparisons to Martin Scorsese, about film, architecture and conquering his nervousness when it's time to head to the Kodak Theater next month.

A little-seen foreign film like "City of God" getting three big nominations seems like a real coup. Were you surprised?

I'm still in shock. We had previously been in the running for best foreign film last year and were not selected, so I thought it just wasn't the academy's kind of film. To have it nominated now is a huge surprise. I'm working in London now on a new project, and my day today was full of meetings. I didn't even pay much attention [to the announcement of nominations], because I never thought it would be nominated.

Will you attend the Oscars?

Of course I'm going to the ceremony, especially since my three best friends are being nominated as well: César Charlone (cinematographer), Daniel Rezende (editor) and (co-writer) Bráulio Mantovani. We're like a gang in Brazil, the people I hang out with on Saturday night. But I've already been to the Golden Globes, because I was nominated for best foreign film, and it's not a very good feeling to be there. I get so nervous. If they could send me the award by post, it'd be much less pressure.

Do all the superstars at the Oscars make you nervous too?

No, it's all people. I've been talking to a lot of stars this week because I'm casting my actress for this next project. At the end of the day, talking to them is the same as talking to everyone else.

"City of God" is very violent, but in past interviews you've distanced yourself and the film from mainstream Hollywood blockbusters. How do you make that distinction?

I try to picture violence not as a show or as entertainment. If you watch "City of God" carefully, you'll see that every opportunity I had to show violence I tried to avoid. We had a rape sequence, but I didn't show the rape. We have a war between two gangs, and in a regular U.S. studio film it would be the most exploited sequence in the film, but when I show this it's far away, it's nighttime. You barely see the violence. Usually when people compare my film with the films of somebody like [Quentin] Tarantino, I think they have nothing to do with each other. It's really the opposite intention. I don't think violence is funny, and I don't think it's entertaining.

Most of the cast in "City of God" is nonprofessional actors. How did you find them and what's your recollection of working together?

It was the most incredible experience I've ever had, and I couldn't have done this film without that kind of casting. I used people from all those slums, and some of the boys even used to be drug dealers before getting involved with our project. So they knew much more than me about the film I was shooting. Sometimes I would come to some of the boys and say, 'What should we do here? What would this guy say?' In the dialogue I had written, I was always telling them the intention for each scene and encouraged them to improvise dialogue. I wanted it to be as authentic as possible, because they knew much more than me. I really think we were partners in the project. They were able to teach me what my film was about.

Do you think places like the "City of God" slums are better or worse today?

I think today it's worse than it was in the '70s, in which the film is set. Drug trafficking is worse. There are some really strong factions controlling things right now. It's more difficult to deal with them than 10 years ago because they're so well organized. But I think Brazil is just changing a lot, just like how the academy is finally nominating subtitled films. [Laughs.] We have a president really focused on social issues, and I think the country will be much, much better. And corruption used to be the biggest issue in Brazil, and it's not such a big deal anymore. Things are really getting better.

You've said that poverty and crime were foreign to you before making "City of God." What's your background?

I'm a middle-class guy from São Paolo, the son of a doctor. I was trained originally as an architect, but in university I got involved working with experimental video, and that led me to independent productions and then commercials. And then my life became boring. I wanted to do something else. So that's what led me to shooting this film.

"City of God" is very sophisticated visually, with lots of moving camera work and quick editing. Is it safe to assume commercials are where you developed your style?

I think all I know about cameras, lenses, editing I learned doing commercials. It was a great way to learn and get paid for it. I think I must have done a thousand commercials before directing "City of God." The last 10 years I've been shooting every week. So all the kinds of problems you can have in production lighting or actors or whatever, I'd been through it already. I'm really an old director even though this is only my second film.

What about your training in architecture -- has that influenced your filmmaking?

I think so. I have really good relation with space: setting up the camera and trying to picture a set. I'm very comfortable imagining everything laid out. If you watch "City of God" only trying to understand what happens to the city and not the characters by watching the background, there's a story being told there too. In the beginning you see a lot of open landscapes. You can see the horizon. Towards the end there's only boys running through corridors, trapped inside their world. There's a story being told through the architecture. It feels totally different from beginning to end.

You mentioned working in London right now. What are you directing next?

I'm working on "The Constant Gardener," a film adapted from a book by John Le Carré. It's about a British diplomat whose wife was killed in Kenya. He tries to find out why his wife was murdered, and along the way he comes to love her like he never did while she was alive. It's also about how the pharmaceutical industry profits from health problems around the world. And it's also a thriller.

It sounds like a departure from "City of God." Do you enjoy directing a wide variety of films?

I'm really moved by challenges. Actually, I don't know how to do this new film, and I'm trying to learn along the way. That's usually how I like to do it. I really like to learn things as I'm doing them. With "City of God," I had never been to that slum, and I knew nothing about drug dealers. I think that when you're getting into a new situation, something you don't know that much about, you have really a fresh look. You're very turned on to everything that's happening, and you're paying attention to the details.

Are you interested in the interest you'll probably receive from Hollywood after the nominations "City of God" received?

I've already been offered something like 60 or 65 projects from American studios in the last year. But at the time, I was working on a personal project, a film called "Intolerance," about globalization. So I read the scripts they sent me, but mostly just to learn how to write them, not because I was really interested in directing them. But by the end of the year I realized that my script for "Intolerance" just wasn't ready to shoot yet, and that's when I decided to do something else. That's when I was offered "The Constant Gardener," and I thought it was an interesting project with good people involved, so I decided to do it. It was just the right script at the right moment. Some of the scripts I'd been offered before were actually really good, and they were hard to turn down. But it's about timing, and "The Constant Gardener" was the script that came to me at the right time.

Shares