It's never a good idea to underestimate a charming, nicely crafted trifle like Woody Allen's "Sweet and Lowdown." Movies that can so effortlessly fox trot you into another time and place for a few hours are rare enough these days. But I can't remember the last time I settled in to enjoy a movie that I knew was going to please me with its gags, its breezy dialog, its satiny look, only to be knocked for a loop -- to fall deeply, deeply in love -- with a specific performance I couldn't have been prepared for. "Sweet and Lowdown" is undeniably pleasant, but British actress Samantha Morton quietly explodes it: Her performance is like nothing I've seen in recent years.

If you were to break Allen's career down into individual five-year rotations, "Sweet and Lowdown" would represent a sunny spot in the latest cycle, especially after the facile and bitterly misogynist "Celebrity" (1998) and the depressingly retrograde sexual politics of "Mighty Aphrodite" (1995). "Sweet and Lowdown" is the kind of effervescent entertainment Allen's capable of making when he takes a breather from pawing desperately at his own neuroses, which ceased to be even remotely interesting long ago (except as they surface in wry amusements like 1993's "Manhattan Murder Mystery," where the fear-of-aging subtext enhances the story instead of sabotaging it).

"Sweet and Lowdown" follows the career of fictional '30s jazz guitarist Emmet Ray (Sean Penn), a professional who's cocksure of his own brilliance except when the subject of Django Reinhardt comes up: Then he turns to jelly, knowing that he's simply no match. Ray is a cartoon sharpster with a pencil moustache and a pompadour that's glazed and pouffed to an almost inhuman scale. Perpetually talking out of the side of his mouth, he's loaded with white hipster jive -- in fact, it's the only way he knows how to communicate. He's less a flesh-and-blood man than a conglomeration of bodacious one-liners ("First time I had sex, 7 years old") who happens to play guitar like a fiend. On the road constantly, he's an unapologetic ladies' man, until he meets Hattie (Morton), a simple-minded, mute laundress. He falls in a kind of love with her -- but even then, when he invites her to come along on the road with him, he's got her changing flat tires as well as doing laundry (his excuse is that he doesn't want to risk damaging his fingers).

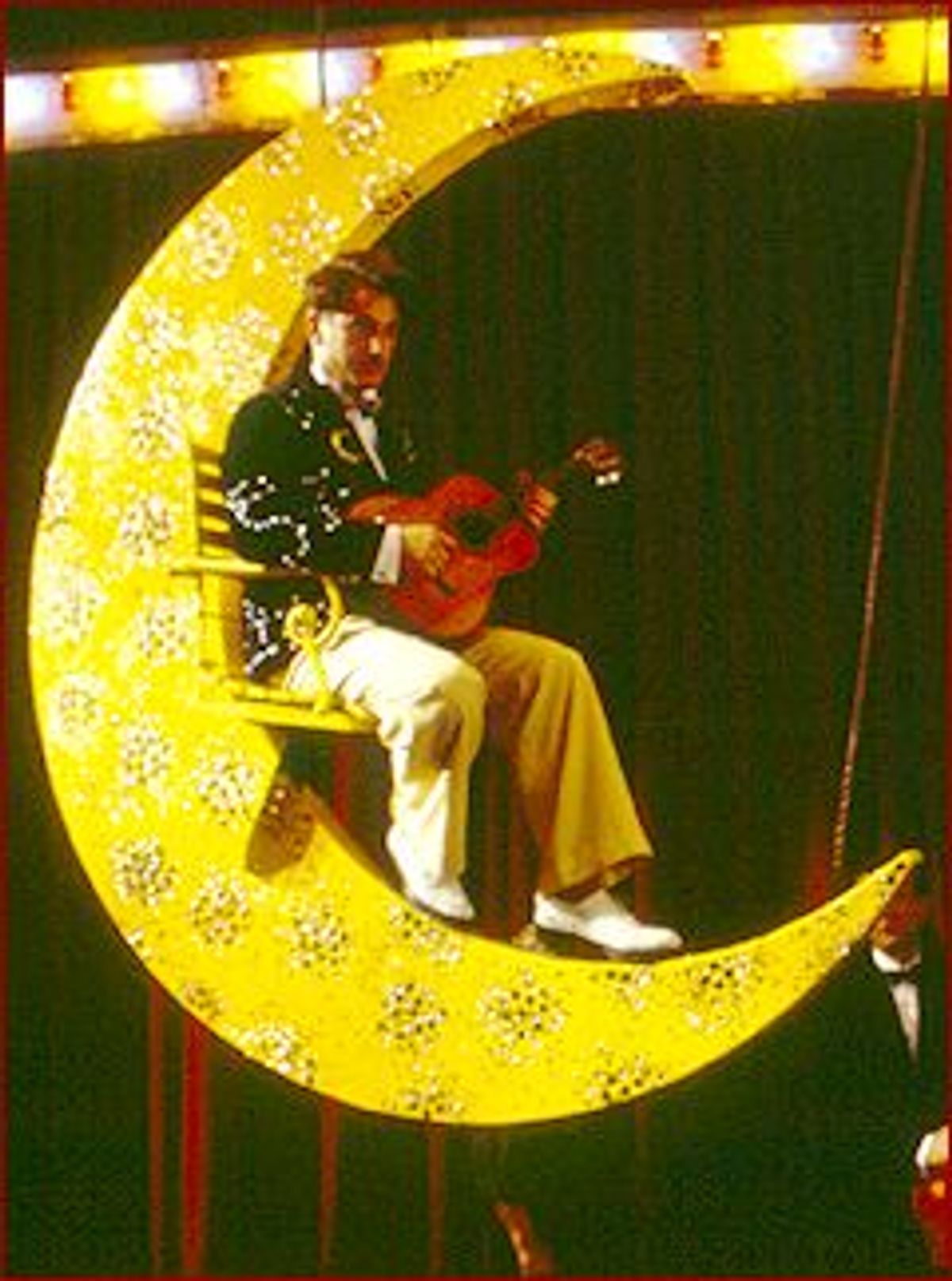

Allen, who both wrote and directed, charts a rambling biographical profile for Ray, complete with documentary-style comments from jazz experts like Nat Hentoff. The picture moves along as a series of vignettes, some of them (one explaining Ray's involvement in a gas-station holdup, for instance) told from more than one point of view, in recognition of the fact that jazz lore is loaded with alternate endings, reckless embellishments and outright fabrications. Allen uses his lightest touch in pulling off some wonderful sight gags, as when Ray gets the idea that he wants to be lowered to the stage in a giant crescent moon as part of his act. He has the moon built to his specifications (out of what appears to be the finest plywood) and then painted and decorated; its shaky descent from the rafters, not to mention what comes after, is sheer silent-comedy style delight.

Allen has a great feel for the '30s; it's a period that always seems to loosen him up, as it did in the 1994 "Bullets Over Broadway." His overwhelming fondness for traditional jazz doesn't hurt any either. Even if you don't recognize tunes like the Ted Lewis Orchestra's "Clarinet Marmalade" (the name alone is so delicious it bears mentioning), you can't miss how the music Allen uses (under the direction of arranger and conductor Dick Hyman) wraps every scene in just the right mood. And cinematographer Zhao Fei ("Raise the Red Lantern") works magic with the dusty roses and greens of nightclub interiors and the cheerfully shabby insides of roadside motels. The whole movie is enveloped by a lush nimbus; it's not so much the glow of nostalgia as it is a gentle reminder that this era is long past, and there's no going back.

It's a relief to find Allen assembling his typically stellar ensemble of actors and actually giving them good work to do. (His misuse of terrific actors like Judy Davis and Kenneth Branagh in "Celebrity" still rankles me.) When Uma Thurman slinks into her first scene, looking more like Marlene Dietrich than ever and wearing a tuxedo just as Dietrich did in "Morocco," she just about smokes off the screen. As the eccentric heiress that Ray impulsively marries, she looks completely at home decked out in Chinese robes and wielding long cigarette holders. John Waters has a far-too-brief cameo as Ray's frustrated manager. His lines are perfectly straight, yet every one comes out hilariously funny; it's a shame the movie doesn't give us more of him.

Penn is great fun as Emmet Ray, the kind of guy who could break your heart with a simple musical phrase but who doesn't have the faintest idea how to love an actual woman. Penn, with that sleazy gleam in his eye, takes the performance just close enough to caricature to keep it entertaining, but he's restrained when it really counts. In the moment when it dawns on him that he's made the biggest mistake of his life, he pulls back so abruptly that his sudden reserve takes you apart.

But I suspect when I look back on "Sweet and Lowdown" in 10 years' time, I'll remember it as belonging solely to Morton. She's the stealth actress of the late '90s: Her leading role in Carine Adler's 1997 "Under the Skin" burrowed deeply into the desperation of mourning and miscued sexuality, and her astonishingly tender and bold performance in another English film, this year's "Dreaming of Joseph Lees," suggests that she's only just begun to tap her resources. According to London Time Out, when Allen offered her the role of Hattie, she insisted on reading the whole script (Allen is known for allowing actors to read only their own lines), claiming that she had several offers and wanted to have a good idea of the project before she took it on. You could call it youthful hubris -- how dare a 22-year-old actress question an ancient, wise, alleged genius? Aside from the fact that Allen's modus operandi is embarrassingly egotistical anyway, when you see Morton's performance, you understand that an actress of her caliber and dedication would have every right to insist on seeing the whole script.

To Allen's credit, he allowed it, and it's a good thing, too. A mute laundress? Could any character sound more sickly and unappealing from that description? But in Morton's hands, the character is a revelation. With her quiet expressiveness she conjures both the glowing presence of great silent-film actresses like Lillian Gish and the crushing vulnerability of Giulietta Masina. And what catches you is that she's most heartbreaking in her happiest moments, not her most crestfallen ones. She's a hearty eater, tucking into her food with so much gusto that you're left with no doubt that a simple doughnut must be the staff of life. Her comic turns are amazing: After spending a day on a movie set being kissed into a trance by a handsome older actor, she stumbles into a pane of plate glass, and her pratfall is both delicate and clumsy, a touch of real genius in terms of its physicality.

But it's her face that really gets you. When she first appears, wearing a middy blouse and a striped hat crunched down over her curly bob, she looks barely 15. As you watch her, though, her elfin features take on an almost ageless radiance. She asks the deepest questions with her eyes alone; her crescent-moon smile lights up her whole face. If her character is set up to be the unwitting receptacle for Emmet Ray's macho cluelessness ("This is my one day off, I want a talking girl," he announces just after they meet), she trumps him in the end. The sensitivity you hear in his guitar is incomplete because it seems to come from nowhere close to his heart; but it plays out on her face, and that's where it finds its meaning. When she hears him playing for the first time -- they've just made love and she's busy hopping back into her comically baggy undergarments -- she stops short, transfixed. It's clear the sound is like nothing she's ever heard, but its beauty hardly compares with the sense of creeping wonder that steals over her face, like a morning glory opening in stop-time.

Like nothing I've ever seen, that instant represents the transformative powers of music, its ability to change you imperceptibly from the inside before you even realize what's happening. And yet as Morton plays that scene, she turns it into something even more than a testament to the power of a few simple notes. She's a metaphor for the idea that even for the most brilliant musician, it's the listener who completes the equation. Morton is music you can see.

Shares