Alan Parker's adaptation of "Angela's Ashes," Frank McCourt's best-selling memoir about his impoverished childhood in Ireland, is right in so many ways. The movie looks appropriate, if a little grand, for its subject matter: Cinematographer Michael Seresin makes those Irish streets look suitably cold and gray and beautiful. The picture's script, by Laura Jones and Parker, is unfailingly faithful to the book: There are no manufactured happy moments, nothing to artificially lighten the weight of McCourt's tenaciously scrappy and heartbreaking story. Robert Carlyle and particularly Emily Watson, as young Frank's dad and mum, carry their roles comfortably, never succumbing to dramatic excess -- difficult to do, when you're playing parents who watch helplessly as three of their babies die.

But "Angela's Ashes," as carefully made as it is, somehow still comes up lacking. Parker's devotion to capturing every significant detail of the book is admirable, but it's possible that his persistence may have steamrolled over some of his passion. "Angela's Ashes" feels like a big movie, epic in scale, even at those times when it should feel intimate, small. John Williams' mercilessly swelling score doesn't help. It barrels in loudly at every predictable turn, cueing us how and what to feel before the subtlety of what the actors are doing has had time to sink in.

The story has so much pathos built into it, it doesn't need enhancing. The story opens in Brooklyn, where young Frank lives with his mother, his father, three brothers and newborn sister. When his baby sister dies, his mother, Angela (Watson), sinks into a depression; some members of her family decide it's best that the family go back to Ireland, and so they do. But Frank's shiftless, though not completely heartless, father Malachy (Carlyle) has no better luck finding work in Ireland than he did in Brooklyn, and his drinking and neglect all but destroy the family. The story of Frank's upbringing proceeds from there, covering his time in school, his illnesses, his adolescent sexual shenanigans, his first encounter with love and, most significantly, his all-consuming desire to get himself back to America.

Maybe one of Parker's problems is that getting details right doesn't necessarily mean that nuances will fall into place as well. Parker uses voice-over narration -- a device that's hard to pull off -- to good effect here. And yet, when you go back and reread McCourt's prose, you can't help feeling that the spoken word of the movie version is missing something. As written, McCourt's cadences ripple as naturally as a forest brook. You get the feeling it's taken him years and years to slip into that voice. When he writes of stealing coins from the moneylender for whom he writes lively and vicious dunning letters (an incident that's also portrayed in the movie), he sounds both mischievous and ruthless in a way that the movie dialogue just doesn't convey:

Sometimes she falls asleep and if the purse drops to the floor I help myself to an extra few shillings for the overtime and the use of all the big new words. There will be less money for the priests and their Masses but how many Masses does a soul need and surely I'm entitled to a few pounds after the way the Church slammed the door in my face?

That's not to say that Parker exactly softens the book. For example, those three babies die fairly early in the movie, and although the picture seems a little slow in gathering steam, it's a testament to Parker's skill and sense of pacing that he can keep an audience with him when they're faced with such devastating circumstances before they've even had a chance to settle into their seats.

But perhaps because McCourt's book became so wildly successful -- I remember a time when everybody seemed to be reading it on the subway, when it was the ubiquitous choice in every book club -- it's come to be viewed as of one of those bittersweet, heartwarming tales of growing up poor. Yet the toughness, the unresolved bitterness, of that book -- as evidenced in the passage quoted above, where McCourt refers to those church doors slamming in his face -- as well as its razorback humor were what stuck with me, and Parker's rendering falls short on picking up those subtleties.

That's not for lack of trying on part of the actors. "Angela's Ashes" is very smartly cast. The three actors who play Frank at different stages of his life (Joe Breen, the kid; Ciaran Owens, the preteen; and Michael Legge, the teenager) are uniformly terrific, and the switch between actors, sometimes so hard to pull off, is never jarring. Legge, in particular, manages some tricky stuff; he's particularly sensitive in a segment where he falls in love for the first time with an exceedingly delicate girl (Kerry Condon), who, it turns out, has tuberculosis.

Other actors, like Pauline McLynn as Frank's stern Aunt Aggie, have some very delicately shaded moments, as when Aggie spontaneously takes Frank out to buy his first suit of clothes. Her generosity shines through her primness without being cloying.

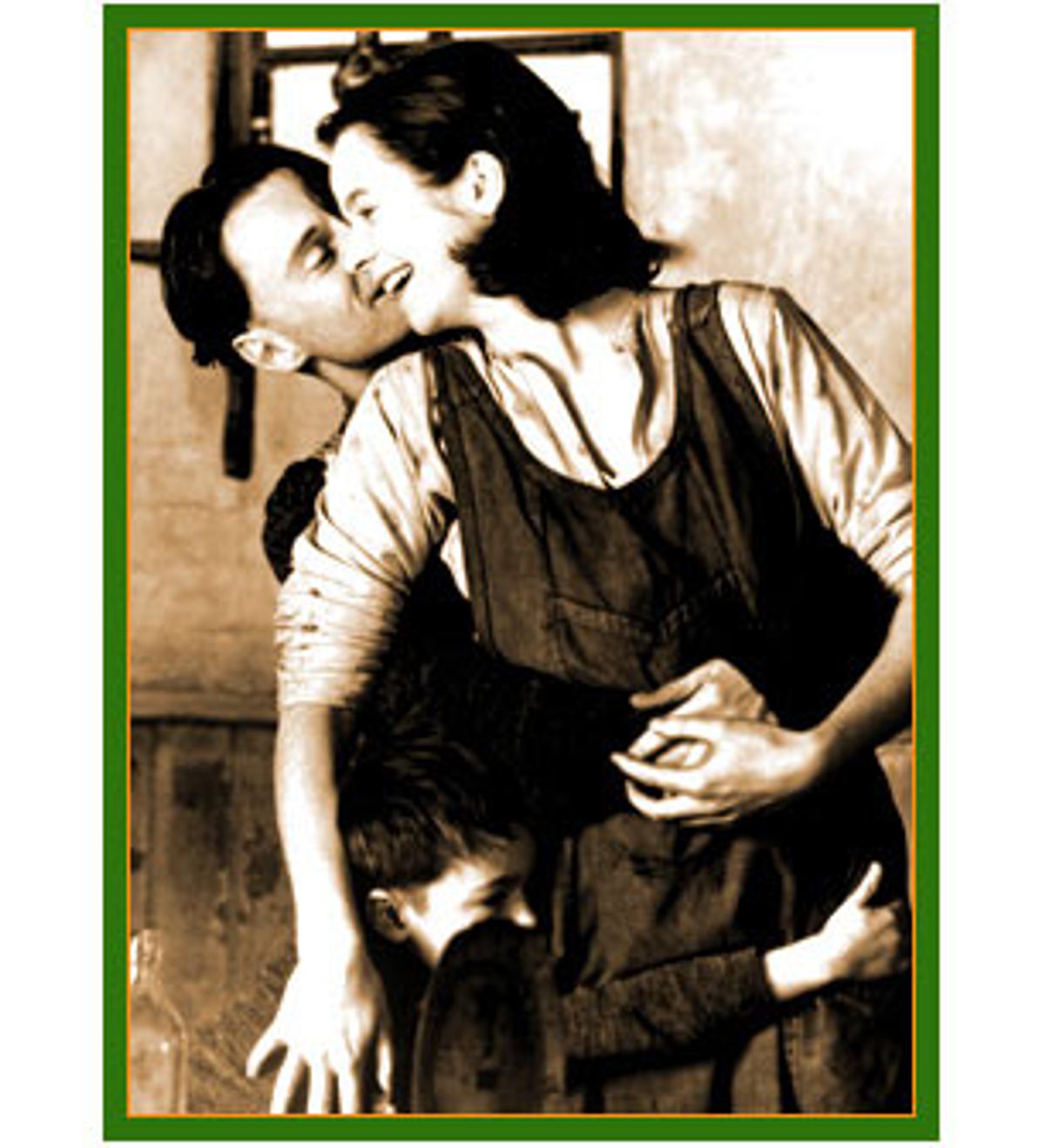

Carlyle, as Malachy, has just enough charm, and just enough coldness, to portray the kind of man who can be teaching his children an old song one minute and heading out to the pub to drink away the family's food money the next. And Emily Watson, as a mother who's forced to raise her large family in squalor as the result of her husband's irresponsibility, is inescapably touching. When the priest at the local rectory rebuffs her and Frank in their efforts to have Frank admitted into training for the priesthood, she admonishes him never to let anyone slam a door in his face again, and her look of shamed anger is the flip side of the weary resignation that otherwise seems to rule her life.

Parker was wise to follow the structure of the book. The picture, like its source material, is a series of connected vignettes instead of a continuous dramatic narrative, and after a somewhat sluggish start, it moves along deftly. Apart from the messed-up but ardent "Magnolia," "Angela's Ashes" is the only holiday movie that made me walk out feeling as if I'd really seen something.

But I just can't escape the feeling that its craftsmanship and its performances should somehow add up to more. "Angela's Ashes" is dramatic, massive in scale, at times very moving. And yet, somehow, it comes up short in terms of essential poetry. The story of Frank McCourt's triumph makes it to the screen intact. It's the lyricism, the heartbeat, that seem to be missing.

Shares