"Boiler Room," writer-director Ben Younger's debut film about young wannabe hotshots who peddle shady stocks over the phone, has any number of things going for it, starting with a decent script and one especially fine actor, Giovanni Ribisi. What's weirdly fascinating about it, though, is the way Younger manages to pull off the same kind of illusion that the movie's sharp young protagonist does: He talks us into buying a bill of goods, and most of the pleasure of watching the picture comes from seeing, and marveling at, how well he does it.

"Boiler Room" is a movie made with confidence that borders on bravado, and sometimes it shows more conviction than it does grace. But it moves along at a brisk clip, and there's almost always an engaging actor to look at or an enjoyably brash volley of dialogue that makes you feel as if you've wandered into the middle of a particularly ruthless squash game. In moviemaking, as in cold-calling, sometimes conviction is almost enough.

For one thing, Younger doesn't make the mistake of simply remaking Oliver Stone's ham-fistedly moralistic "Wall Street" (he seems to realize that no filmmaker in his or her right mind would want to), nor does he tire himself out trying to drive home the immorality and clueless depravity of contemporary young men, the way Neil LaBute does in the flaccid and ineffectual "In the Company of Men."

There are some things Younger throws into "Boiler Room" that he just doesn't need: The central character, Ribisi's Seth Davis, yearns to win the approval of his no-nonsense judge dad (played with droning predictability by Ron Rifkin), and that angle of the plot ends up feeling like a cheap ploy to explain why an essentially good boy is willing to involve himself in unsavory stock market dealings -- as if old-fashioned greed just weren't interesting enough.

Luckily, though, Younger never completely underestimates the power of greed. He recognizes it as the main motivator that would draw young men -- and these are all men; women aren't especially welcome -- to a boiler room in the first place. In the movie's terms, a boiler room is the nerve center (here, it's a tacky gymnasium-like room crowded with desks, phones and fast-talking young guys) of a less than completely reputable hard-sell brokerage, the kind of firm that makes money by pressuring customers into buying stock in unknown or bogus companies. The firm's brokers make huge commissions off these sales, and may not even have to lift a finger to do so; their calls are often made by foot soldiers who haven't yet passed the Series Seven (the exam that gives stockbrokers legal status) -- who have no choice but to pass along whatever accounts they happen to land.

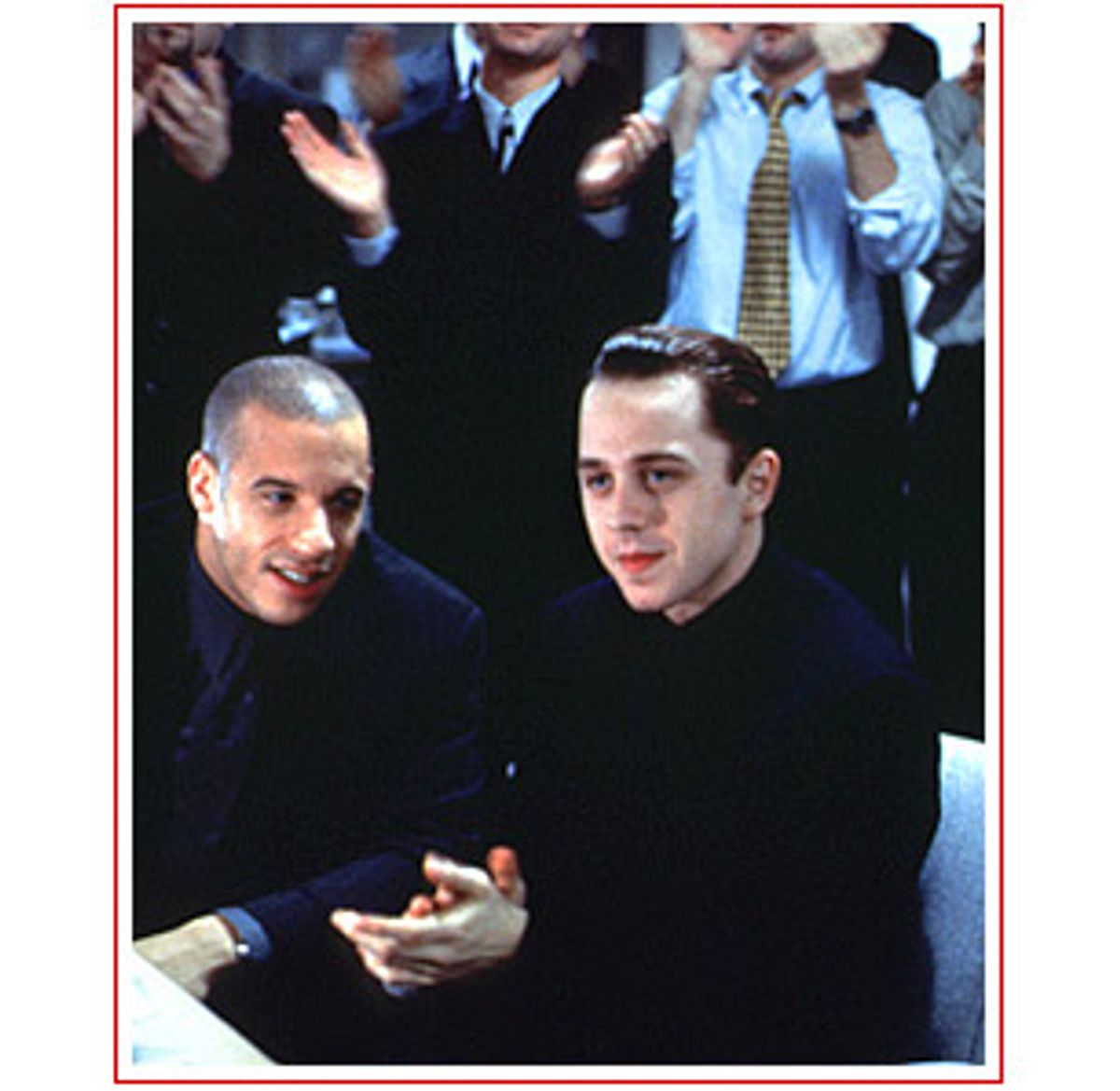

Seth, a college dropout who's running an illegal but extremely profitable casino out of his Queens apartment, is lured into a boiler room when a broker from the questionably named J.T. Marlin -- not to be confused with J.P. Morgan, unless you're a hapless sap on the other end of the phone line -- drops by to visit in his flashy new sports car. That broker, Greg (Nicky Katt), and one of his buddies, Chris (Vin Diesel), show Seth the ropes, coaching him in the process of contacting leads by phone and hanging on like a terrier until they've agreed to buy the proffered stock. The boiler room is a place where bad boys can thrive: Their bible is David Mamet's "Glengarry Glen Ross," and sexism runs rampant (broker trainees are told that under no circumstances should they "pitch the bitch," in other words, sell stock to women).

In the brokers' off-hours, they hang out in Greg's huge, gorgeous, practically empty apartment (its central furnishings are a leather couch, a massive TV and a tanning bed), wearing tacky tracksuits and mimicking Michael Douglas' most memorable lines from "Wall Street." There's a certain amount of camaraderie, but competitiveness always takes precedence over loyalty. Early on, it's playful, almost affectionate, when Greg (who, like Seth, is Jewish) tells the Italian-American Chris, "Why don't you go back to Little Italy?" and Chris shoots back, "Why don't you go make me a latke, dreidel boy?" But it's not long before you sense the seething animosity that simmers beneath their jokes.

Even so, the essentially decent Seth ends up thriving in this atmosphere: He's admirably adept at cold-calling; he passes his Series Seven with flying colors; and he even falls in love with the firm's beautiful but tough-minded receptionist, one of its few female employees, Abby (Nia Long). You notice how, as he gets the hang of boiler room life, he starts to wear trimmer shirts, nicer ties, a watch that's somehow both flashier and more understated than his old, blobby digital model. But Seth is smart enough to know that this kind of money shouldn't come so easily, and when he starts digging into the firm's background, he begins to have second thoughts about his newfound success.

If you toss out the Psych 101 father-dad trauma, "Boiler Room" ends up working nicely as a kind of minithriller revolving around one man's crisis of conscience. Younger is quite the wily lad himself. One of the first things that strikes you is the way he has cast young actors with familiar, trustworthy faces -- notably, Ben Affleck in a small role as an aggressive, jauntily snotty J.T. Marlin recruiter, and Tom Everett Scott, who barely looks old enough to shave, as the firm's wunderkind chairman -- as money-hungry wheeler-dealers. To his credit, Younger takes care not to make his characters unlikable -- the easy route for moviemakers who hope to expose the banality of venality.

Younger knows there's nothing to expose. He doesn't approve of the boiler room kids' behavior, but he resists making a judgment about their desire to make money, and it's a refreshing approach. One shot of Seth's Queens apartment/casino, furnished with a mix of dorm-room rejects and '70s Mediterranean leftovers, is all you need to understand why a beautiful, impeccably tailored suit just might appeal to him. And when we've decided that the J.T. Marlin guys are just like all those arrogant young financial-whiz types we've ever looked at askance on the subway or in a tony nightclub, Younger pits them against a group of infinitely snobbier Ivy League-educated brokers in a barroom skirmish -- making the point that in the pecking order of the financial world, go-getters like the boiler room boys are really just pathetic underdogs. Younger asks us to have some sympathy for them, but never pity.

Younger's a bit of a gunslinger with dialogue ("What are you, last night's erection?"), but his actors know how to run with it. Long's Abby is particularly appealing -- there's an almost frightening resoluteness lurking beneath the surface of her soft features. And Younger doesn't make a big deal out of the fact that Abby and Seth's romance is an interracial one. He's even audacious enough to give Seth a jokey line about it.

When Abby happens upon Seth riffling through some files, she asks him what he's looking for, and he replies in a honeyed voice, "I'm just looking for some chocolate love." In addition to being the kind of corny flirtation that all real-life couples engage in, it's also a completely believable line for the character. Younger gets the opportunity to make a big statement and, thankfully, passes on it.

Younger clearly took great care in casting his lead characters. Both the aggressiveness and the almost crippling insecurity of Katt's Greg are written on his face: His heavy brow might mark him as one of the bad guys, but his soft, full lips sometimes make him look like a little boy who's about to cry. And Younger really knows how to use Ribisi's looks to hit us where we live. Ribisi, a wonderful, consistently subtle actor, slips into the plan beautifully: It's a case where director and actor work the perfect con.

It would be one thing to watch an eminently handsome and disreputable-looking actor like, say, Peter Gallagher hop on the phone and coax some poor sod into forking over his life savings for a lump of stock that's certain to go nowhere. But seeing Ribisi do it almost kills you. As you take in the whole package -- his virtually chinless profile (he's like an unwittingly sexy Dagwood Bumstead) and his Victorian cupid's-bow of a smile -- there's something deeply unsettling about the way the lies roll off his tongue.

But Ribisi doesn't so much hammer on the immorality of those lies as illuminate their sheer inappropriateness for anyone who's trying to live a decent life. It's a smudgy distinction that a less astute actor might have missed, and it's one of the things that make "Boiler Room" cut just a bit deeper than it otherwise might have. Ribisi, with his innocent good looks, may buy low, but he always sells high -- sometimes high enough to send you reeling.

Shares