"Judy Berlin," the debut from writer-director Eric Mendelsohn, recalls Jean Renoir's remark that there is no realism in American movies, but something better: great truth. Within its modest scale, Mendelsohn's grave and fanciful film is an almost perfectly realized poetic vision of people who continue in their everyday existence certain that life in a larger sense has passed them by. It is also a very unfashionable movie for a young filmmaker to make right now.

In the past few years, the suburbs have reemerged as the favorite whipping boy of the hipoisie, from the adolescent temper tantrum of "Happiness" to the wolf-in-sheep's-clothing contempt of the sterile objet d'art "American Beauty." These movies revel in two clichis to which movie critics are particularly susceptible: the clichi of suburbs as stultifying traps of conformity, allowing critics the luxury of feeling superior to the people on-screen, and the clichi that a pessimistic film is inherently truer and more daring than one that admits even a flicker of hope, allowing critics to paint themselves as able to face the hard, dirty truth.

Filmmakers and novelists have tended to treat the physical surface of the suburbs -- the houses that look the same, the well-tended lawns and gardens, the post offices and schools and churches and supermarkets -- as if they were indistinguishable from the emotional lives of the people who live there. And when they've allowed that the inner life of suburbanites might not be as placid or cheerful as their surroundings, they've often used inner turmoil as evidence to show that suburban life is based on a lie. (Presumably, urban neurotics are more honest for choosing a locale that approximates the chaotic uncertainty in their heads.)

Mendelsohn doesn't so much reject that view as consider it beneath any filmmaker who aspires to maturity. One of his characters is David Gold (Aaron Harnick), a failed young filmmaker who has retreated from Los Angeles to his parents' home in Babylon, Long Island. "I always wanted to make a documentary about this town, but not sarcastic," the director has him say at one point. (Babylon also happens to be the hometown of Mendelsohn.) "Judy Berlin" is the fulfillment of David's wish.

The details of the suburban life Mendelsohn shows us -- the split-level houses with wall-to-wall carpeting and wrought-iron railings leading from one floor to the next, a lighted cabinet of porcelain figurines -- may not be to his liking, but neither are they his excuse to condemn the bad taste of his characters. Mendelsohn grew up in living rooms and kitchens and bedrooms and schoolrooms like these, and he treats them with affectionate, if not nostalgic, recognition. Middle-class prosperity hasn't saved the characters in "Judy Berlin" from unhappiness or doubt, but it hasn't turned them into the insensate cartoon monsters depicted by Todd Solondz and Sam Mendes. They carry on with their jobs and lives, but they can't help suspecting life holds only more of the deadeningly familiar.

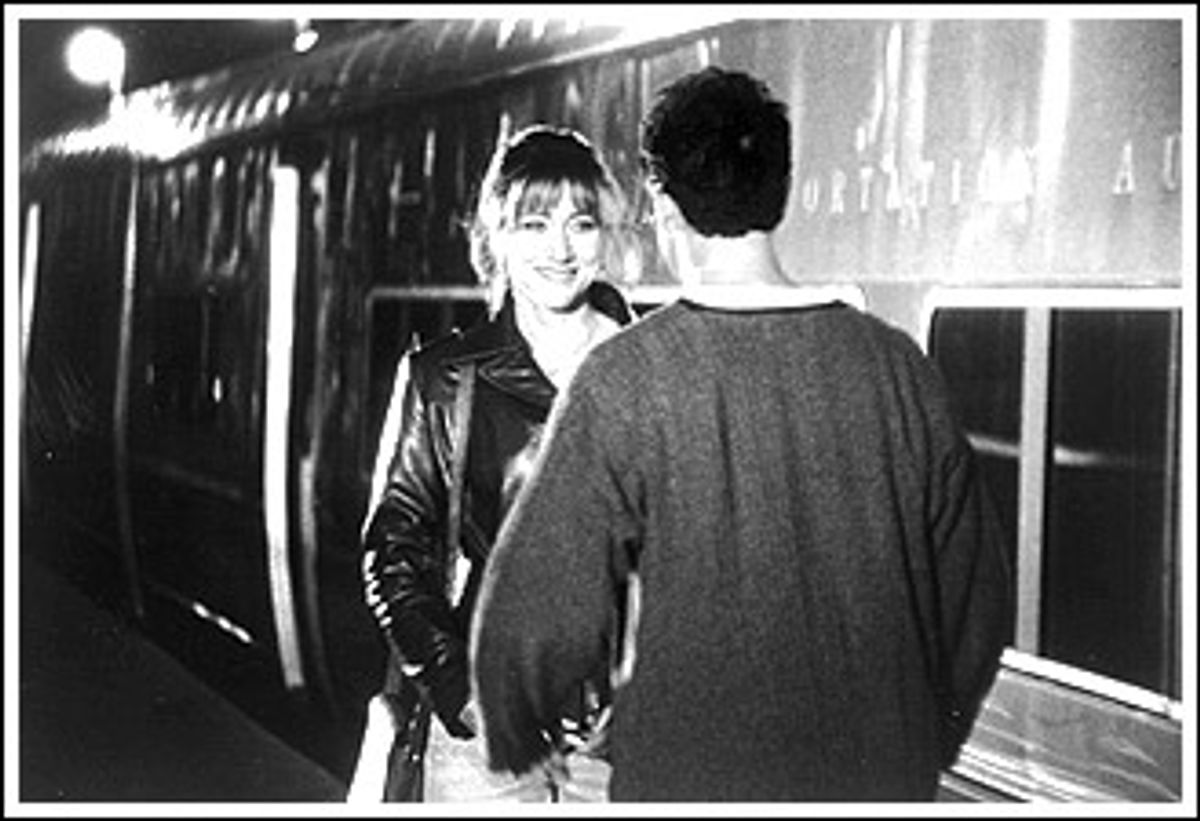

The exception is the title character (Edie Falco, of "The Sopranos"), who leaves home at 32 to make it as an actress in L.A., the same trip David has returned from, broken. In the hours before she heads out, Judy runs into David, whom she had a crush on in high school. Wearing braces that become visible whenever a smile creases her face (which is frequently), Falco plays Judy with hearty guilelessness. Her undiminished enthusiasm makes for a sweetly comic mismatch with David's tail-between-his-legs recessiveness. Judy hasn't a clue what awaits her in L.A., and yet David can't help responding to her, can't help shrugging off the mantle of depressive putz that he carries around with him like a 50-pound weight. (Aaron Harnick takes David from initially unlikable to very touching.) Judy and David's encounter is only one of the stories Mendelsohn is telling in this ensemble piece, but it's a kind of paradigm for the other ones, a quiet confrontation between expectation and disappointment, and a realization that it's possible to live between the two.

"Judy Berlin" takes place over the course of a prematurely cold fall afternoon, during a solar eclipse that goes on for hours and casts a sort of spell over the town. The meaning of the eclipse remains -- wisely, on Mendelsohn's part -- elusive. But it's as if this gentle and unsettling reordering of the natural world in which day becomes night frees people to face what's in their hearts and to see what's in front of them. Throughout the movie, people appear on their front lawns, looking at the streets and trees and houses as if they've never taken them in before. The fine-hued gradation of light and shadow in Jeffrey Seckendorf's black-and-white photography gives the setting the muffled, quizzical impact of seeing something familiar for the first time.

First films are traditionally bursts of energy and ambition, a young filmmaker's chance to crow, "Lookee what I can do!" The low-key assurance of "Judy Berlin" seems more suited to an older filmmaker. If it were from Europe, it might be talked of in the same breath with Claude Sautet or Andri Tichini's studies of the contingencies of middle-aged life. And yet it has none of the bell-jar awkwardness that usually results when American filmmakers try to ape European styles.

Some critics have already compared Mendelsohn to Woody Allen -- he worked on several of Allen's films, this film is in black and white, the characters are Jewish -- but it's a false comparison. When Allen worked in a style similar to the one Mendelsohn uses here (in films like "Crimes and Misdemeanors," "Another Woman," "Interiors"), he barely moved his camera lest it disturb the pristine composition of his shots. The WASP tastefulness was oppressive, the frequent silences dead. Silences punctuate "Judy Berlin," but there isn't one that's not alive with what the characters are leaving unsaid. It takes remarkable empathy for a young filmmaker (Mendelsohn is in his early 30s) to summon up the unforced compassion he shows for middle-aged people who could so easily be regarded as failures. Mendelsohn combines real decency with a love for actors, and at the heart of "Judy Berlin" is a trio of exquisite performances.

As Judy's mother Sue, an elementary-school teacher, Barbara Barrie creates a character so recognizably real that you feel if you were to pull out your old class photos she'd be there standing next to you. Sue is resented by her peers because she treats them the same way she does her students -- with the same praising or admonishing solicitousness. Sue, in her element in the classroom, is helplessly distanced from adults. With just the set of her mouth, Barrie conveys the pain of a woman who can't reconcile her certainty about the way things should be with the disdain it brings her. We've all known someone like Sue, and the brilliance of Barrie's performance is that she lets us see both how Sue irritates people and how she's helpless to be other than who she is.

If you've been lucky enough to see Bob Dishy onstage, you know the joy he's capable of giving an audience. As Arthur Gold, David's father and the principal of the elementary school where Sue teaches, Dishy has the best film role he's ever gotten. (He's had unmemorable appearances in movies like "Brighton Beach Memoirs" and "Don Juan DeMarco.") The slight buoy Arthur receives from the adoration of the people he works with isn't enough to remove the disappointment he carries in the lines under his eyes and on the shoulders of his educator's respectable tweed suit. Dishy has taken on the baggy look of an American Everyman, and this performance is close to an unsentimental definition of the type. The poignancy is that his Arthur can't blame the fates; he's an Everyman burdened by the consciousness of his own shortcomings.

And as Dishy's wife, Alice, Madeline Kahn, in her final film appearance, gives the performance of her life. In Mel Brooks' films, Kahn was the red-hot mama as voluptuous comic whirligig. At first glance, she seemed all dimples and curves and ruffles -- until that operatically trained voice let loose some raucous exclamation and she became the embodiment of dirty-minded farce. (Watch her as the Empress Nympho in "History of the World -- Part I" choosing her escorts for a Roman orgy and turning a string of yeses and nos into a breathlessly lubricious aria.) As Alice, Kahn seems physically smaller, lighter, as if she's retreated into her fancies. She's a flighty Jewish mother as Anton Chekhov might have imagined her.

Alice knows that everything is slipping away from her -- her son, her marriage (the opening scenes where she playfully, but needily, begs for her husband's endearments, are heartbreaking) -- and she tries to hold onto it with a show of loopy good humor. Walking the darkened streets with her maid (the two are pretending to be moon explorers), or exclaiming over the remodeled kitchen of a neighbor she'd cut dead months before, Kahn never allows Alice's desperation to connect to rise to the surface. And yet it's there in every overeager hello, every forced joke, every attempt to conduct life as whimsy. Funny and at times unbearably sad, Kahn's performance is as lovely a swan song as we could ask for. Mendelsohn wrote and directed the character with love. I'm sure he never dreamed that love would be his gift to her memory.

Shares