A few years back, cartoon fans got a glimpse of the dazzling energy behind England's Aardman Animations in a live-action short called "State of the Art." You could see the company's risk-taking puppet animators use the same tricks as traditional Disney-style animators to get a character's expressions down pat -- time-honored techniques like mouthing words in a mirror to previously recorded soundtracks. But the Aardman fellows work with claylike figures and miniature sets instead of ink. And their trademark is the construction of a parallel universe that simultaneously mirrors and intensifies workaday life while comically distorting everything in it. Entering an Aardman creation can be like walking into your office or your living room and finding it turned into a fun house.

Nick Park made the studio internationally famous with immensely charming two-reelers about a stolid, cheese-loving inventor named Wallace -- who devises elaborate Veg-O-Matic-like contraptions for his own supposed comfort and convenience -- and his sane, long-suffering dog, Gromit, who holds the household together. The most expressive jut-jawed, marble-eyed and square-headed creatures in movie history, Wallace and Gromit have become icons of a cracked yet creative domesticity. But some think that Park's short "Creature Comforts," which matches whimsical zoo animals with words taken from humans with similar gripes (like nursing home residents or foreign students), is even more inspired. In the most ticklish scenes, a Brazilian exchange student who hates England vocalizes the frustration of a jaguar from the South American jungles -- a Latin relative of the Pink Panther -- who would gladly trade Anglo technological perks, like double-glazed windows, for green tropics, clear weather and space. It's primordially funny: one of the few cartoons of any kind that get adults to laugh as helplessly as kids.

Greenery, good weather and space are not so different from what the chickens want in Park's glorious feature debut, "Chicken Run," which he co-directed with Aardman's godfather, Peter Lord. But these birds aren't just dissatisfied -- they're fighting for their lives. The day a hen on Tweedy's Farm fails to lay an egg, Mrs. Tweedy decapitates the bird and cooks the corpse for supper. And when Mrs. Tweedy declares she's "tired of making minuscule profits," she happens on a magazine ad that asks, "Tired of making minuscule profits?" -- and purchases a chicken-pie-making machine that threatens to massacre her poultry in one fell swoop.

When these chickens shake their wings at Fate, what results is a soaring testament to the spirit of freedom-loving poultry everywhere, and a harrowing yet hilarious tribute to a hen's ability to endure -- and prevail. As you can tell, just trying to describe "Chicken Run" can put one into the state of euphoric silliness that must have engulfed Park and Lord when they first thought of redoing "The Great Escape" with silicone-and-Plasticine chickens. As the provincial hens, a grizzled Royal Air Force vet rooster and a cocky vagabond Yank unite to fly the coop, the co-directors operate at a plane where ingenuity meets genius.

You may not wind up believing that chickens can fly -- at least not by flapping their own wings. But you will believe that an escape-starved hen can mark time in solitary by bouncing a Brussels sprout the way Steve McQueen bounced a baseball in "The Great Escape." You'll even believe that a rooster can perform McQueen's trick motorcycle riding on a tricycle.

This movie's cornucopia of humorous riffs and stunts never fails to amuse or enthrall because it never ceases to be unexpected. More important, it stays true to Park and Lord's hands-on aesthetic. In an age of gratuitous technowizardry, this is largely a handmade film. It's like a cross between "Babe" and Terry Gilliam or Monty Python pictures (two of which, you might recall, were made for Hand Made Films, George Harrison's company).

When "Babe" premiered to wide acclaim five summers ago, dissenters regarded it as glorified kitsch. But if kitsch is marked by its refusal to acknowledge the grime and muck of mortality, "Babe" and "Chicken Run" are anything but. They may be full of barnyard humor, but they're full of graveyard humor, too. If Park and Lord stylize the birds in "Chicken Run" until they resemble doorknobs with spindly necks and legs, it's to make them more emotive and uproarious, not conventionally cuter. Adorned with what the Aardman gang calls "fluffles" -- scallop-shaped textures that suggest feathery skin -- these chickens have a surface like dented rubber kickballs, as well as malleable brows and oblong beaks full of teeth that tie them to Wallace and Gromit.

The greatest live-action filmmakers, who approach movies as a popular art, trust every segment of the audience to get the gist of a scene. As makers of a "family movie" with an unqualified G rating, Park and Lord carry that trust even further, banking on their own ability to touch moviegoers not just from all backgrounds but also of all ages. They succeed because they're genuine -- genuinely heartfelt, genuinely playful, genuinely satirical -- and also because, in "Chicken Run," they come up with an authentic heroine: a can-do hen named Ginger.

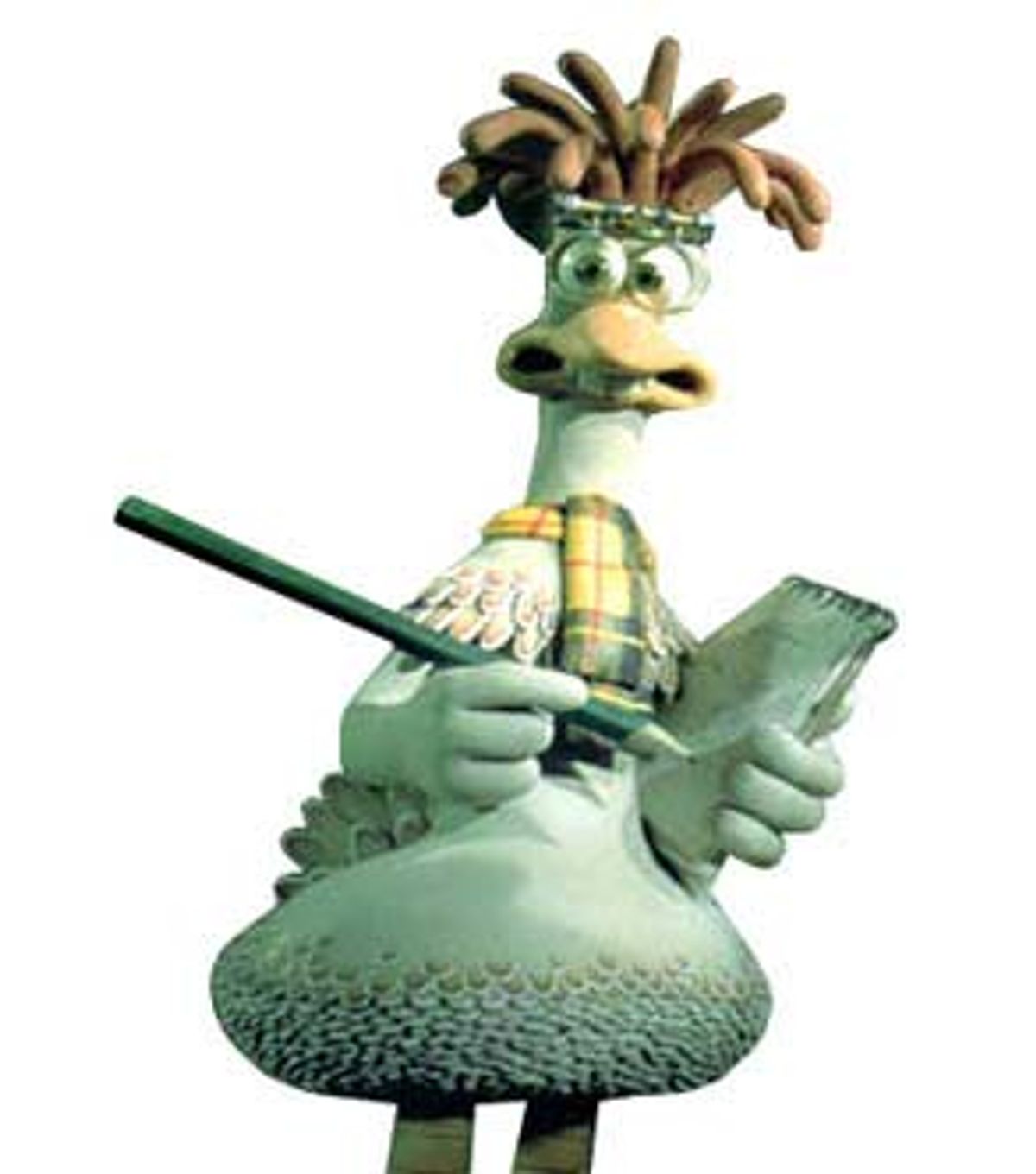

Throughout the film, Park and Lord toy giddily with our received notions of chickens as cowardly and feckless creatures prone to chaotic behavior. Ginger, who knows that each hen is doomed as soon as she ceases to lay eggs, refuses to cater to the flighty or complacent elements in her species' makeup. With the help of a bespectacled Scot with a tartan cravat, Mac; a muscular hen-of-the-masses, Bunty; and even a dim, constantly knitting nester, Babs, Ginger galvanizes her flock in one daring escape plan after another, all hatched in the aptly named Hut 17.

Only once does Ginger contemplate defeat: "The only way out of here is wrapped in pastry," she moans. She redefines what "pluck" would mean for chickens. With her beak clamped in determination and two knobs of her hen's comb jutting out from under her green watch cap like a "V for victory" insignia, she's the rare regular-gal movie leader who's as charismatic as a showboat.

To wax Aardmanesque for a second, if she'd played Eisenhower or Bradley in "Patton," George C. Scott would not have been the whole show. The highest-ranking officer in the military pecking order is Fowler, the rooster who calls roll each morning instead of merely cock-a-doodle-doo. But Ginger is the planner and energizer who gets her hordes to follow her because of her truthfulness and gumption. Sure, when American cockerel Rocky improbably soars onto Tweedy's Farm, he becomes the center of attention -- partly thanks to Ginger, who believes that he'll be able to teach her and the rest of the chickens to fly. And yes, Rocky does play the typical role of Yanks in Anglo-American escape movies: He remains upbeat or breezy when the weight of Ginger's honesty gets too heavy for the room.

But Rocky takes his licks long before the picture is through. "Pushy Americans, always showing up late for every war," growls Fowler almost immediately. "Overpaid, oversexed and over here!" The lighthearted fun that "Chicken Run" has with "The Great Escape" is rooted in the way Park and Lord and their screenwriter, Karey Kirkpatrick, make all the Anglo-American conflicts gleefully explicit. Rocky, the McQueen-like cock of the walk, is a bold, highflying loner whose theme song is "The Wanderer." But he's also an incorrigible glad-hander and opportunist. His hedonism is part of his charm: Nursing a broken wing in a makeshift Jacuzzi as a bevy of hens caters to his whims, he resembles Walter Huston lolling in a hammock among the geishalike Mexican beauties of "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre."

Unlike America's favorite cartoon superhero, Superman, Rocky the superchicken doesn't put truth and justice at the top of his priority list. His version of "the American way" is to tell the public what it wants to hear. Although he may be right that hard-boiled Ginger needs some softening up, it's Ginger who holds the coop together when Rocky's shortcomings crash their collective hope. Yet the movie remains, in its own chickeny fashion, a romantic adventure comedy -- or maybe an adventure comedy romance. It climaxes with a slap, a tickle and a clinch.

Since the Bristol-based Aardman animators have come to be viewed in Britain, as Park sheepishly admits, "as a national treasure," their decision to team up with Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg at DreamWorks has been a source of suspicion on the home front. But Park and Lord share as much with the Spielberg of the Indiana Jones movies as they do with the Katzenberg who helped produce "Beauty and the Beast" -- indeed, Rocky and Ginger's flight through a chicken-pie-making machine out-Indies Indy. And throughout, the sustained flights of physical comedy recall how much of America's slapstick and screwball traditions came from transplanted English music-hall performers like Charlie Chaplin and Cary Grant.

"Chicken Run" reminds us that the fabled "Yankee ingenuity" is rooted in British ingenuity. Before reading the just-issued "Chicken Run: Hatching the Movie" (Abrams, 2000), I would have called the elaborate pie-making machine a Rube Goldberg creation. But Park and Lord's primary inspiration was a parallel British figure named William Heath Robinson, whose cartoon machines are described as appearing to have been "put together by a resourceful amateur whose construction methods included liberal use of tape and bits of badly knotted string."

The air of a "resourceful amateur" breathes unruly life into all the Aardman group's choices. With them, cleverness and intuition go together, not just in the mechanics but in the characterization and the storytelling. For a split second, you may wonder why the prime villain would be Mrs. Tweedy of Tweedy's Farm and not her husband. But then you realize how right it is for her to be the antagonist of all these fine fluffy heroines -- and how ticklish it is to have the clueless Mr. Tweedy turn out to be multiply henpecked. Beyond that, there's an aura of "Psycho" around the Tweedy house: The missus, when she swings an ax, bears a notable resemblance to Norman Bates' mother.

Of course, Park's three Wallace and Gromit shorts already combined Hitchcockian tension and homegrown whimsy. But in partnership with Lord, Park mixes new ingredients into that combination and sustains the blend for 80 minutes. For example, the Aardman group usually works with people off the street instead of scripted actors, and in Park's most renowned works, Gromit is silent and Wallace is a man of minimum words. But in "Chicken Run," Park and Lord get delicious vocal performances from the likes of Mel Gibson as Rocky, Julie Sawalha as Ginger and Jane Horrocks as Babs.

It's no wonder that Sawalha and Horrocks take to their outrageous tasks like ducks to water or chickens to feed: They're both graduates of the cutting-edge TV comedy "Absolutely Fabulous," in which Sawalha played woebegone daughter Saffron and Horrocks played daffy office assistant Bubble. Indeed, in "Chicken Run," Sawalha's stirring stalwartness and Horrocks' infectious ditziness extend those earlier characterizations. But Gibson gets right into the swing of things, too, with a light and engaging self-mockery beyond the grasp of most action-hero peers. And with Mike Leigh regular Timothy Spall and Phil Daniels of "Quadrophenia" as an Artful and an Artless Dodger who happen to be rats, Lynn Ferguson as bristling-brogued Mac and Imelda Staunton as the disputatious Bunty, the movie delights your ears even as it pops your eyes.

Like all the most innovative comic filmmakers, Park and Lord awaken you to the power of the movie frame and to the vitality of its contents. You get swept up in the bustling barrens of the vast chicken-farm set without ever stopping to think, "What a striking and original conception!" The movie is full of fluky design masterstrokes. Sometimes they relate to character, as in Babs' no-brow facial modeling. Sometimes they detonate gags or story points or both, like the torn circus poster that floats down to Tweedy's Farm and establishes Rocky in Ginger's mind as a flying rooster. By the end, they conjure up a sense of wonder that's both funky and transcendent, with a flying machine that in its own G-rated way reminded me of the R. Crumb rocket powered by millions of Chinese blowing through straws. If you think you won't know where to look first, rest assured that Park and Lord are deft enough directors to guide you. If God is in the details, the Aardman animators have given him a solid base in Bristol.

Shares