There's a certain kind of man who wouldn't be capable of fashioning an autobiographical tale that wasn't mostly about women; Cameron Crowe is one of them. "Almost Famous" is Crowe's semiautobiographical account of a 15-year-old journalist who goes on the road with a fictional rock band in 1973, on assignment for Rolling Stone. The movie is somewhat formless, a little too ramshackle in places, its significant moments sometimes only partially connected, like the doodles in the margins of a school kid's notebook.

But "Almost Famous" is sweet at its core: It's far from being a rock-boy fantasy, and you can't even call it a tender valentine to a past era -- it's more like a love letter to a vibe. Ostensibly, the picture is about the adventures of a smart kid who gets to hang out with rock bands, but "Almost Famous" is really about something else, a subject that comes to the fore gradually and subtly, like a shimmery stand of trees down a stretch of hot road that almost don't look real until you've actually passed them.

Like rock 'n' roll itself, the movie's really all about girls. Even when -- no, especially when -- it's pretending not to be.

It was clearly Crowe's intent to tell a version of his own story: An affable and intelligent kid, he made a name for himself as a journalist while still a teenager, writing sharply observed profiles of bands like Led Zeppelin and the Allman Brothers for Rolling Stone. The elfin hero of "Almost Famous," William Miller (Patrick Fugit), is charming and likable, supremely sympathetic in spite of all his eager ambitions. Early on in the picture, he approaches his idol Lester Bangs, the then-as-now-legendary writer and editor of Creem (brought to life beautifully, with scuffed-up irascibility and a not-insignificant gut, by Philip Seymour Hoffman).

Bangs, a fairy godmother in a Guess Who T-shirt, warns William not to get too cozy with the bands he's hoping to write about, and also informs him that the truly exciting era of rock 'n' roll is over: "You got here just in time for the death rattle." Still, he's impressed with William -- probably with his "Sure, go ahead, eat me alive!" innocence as much as with his enthusiasm -- and offers him $35 to write 1,000 words on a Black Sabbath concert.

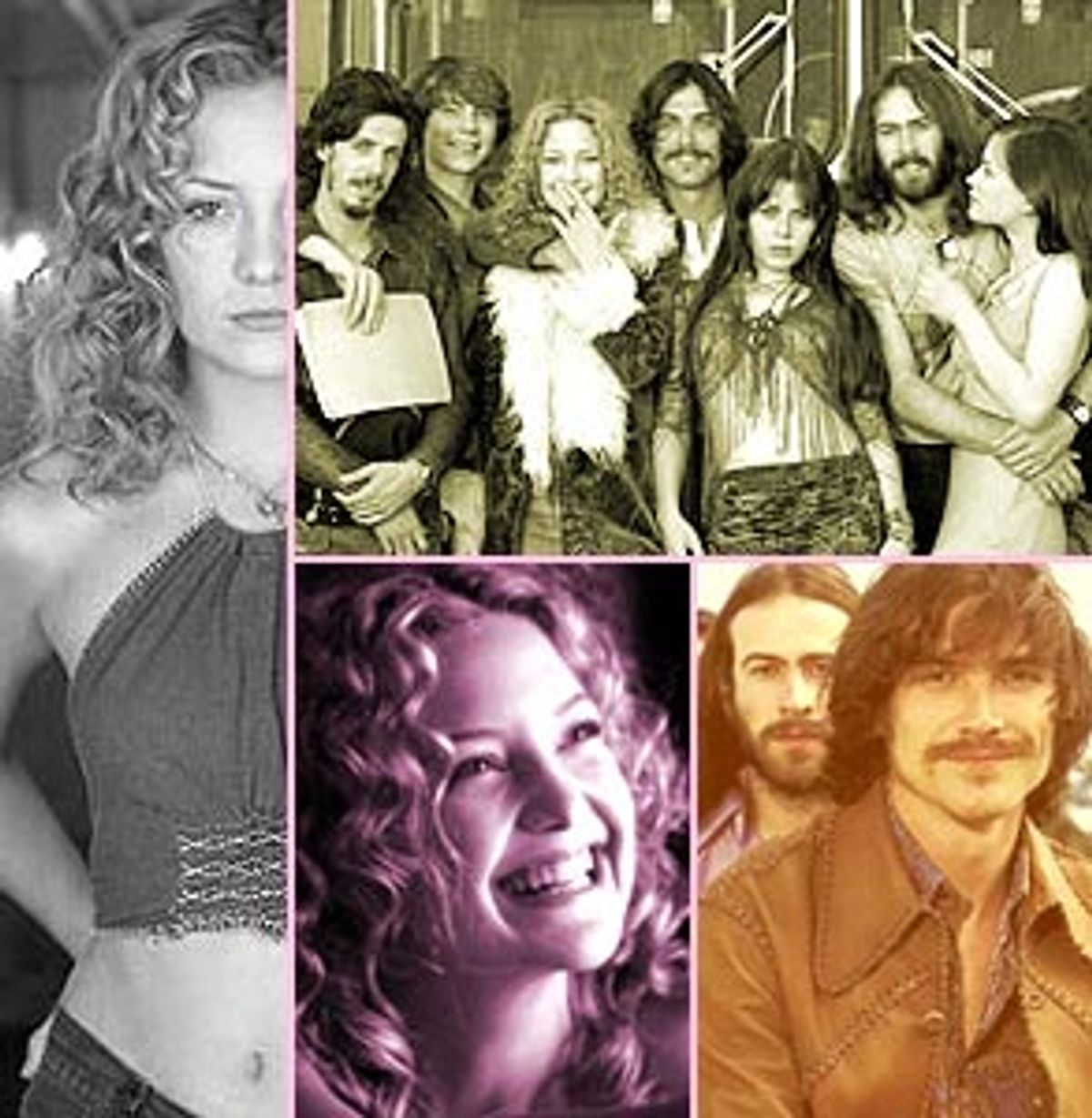

William heads off to the show, dropped off by his neurotic, intellectual, highly protective but undoubtedly loving mother (Frances McDormand, giving the role just the right amounts of muscle and vulnerability), who calls out after him, just as he's passing a herd of girls, "Don't take drugs!" Using his guileless wiles, he tries to wangle his way backstage to interview the band, but barely manages to get a word with the band's opening act, fictitious blues-rock outfit Stillwater. He does have the good fortune to meet a young fan, a head-swimmingly radiant blond named Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), who despises the word "groupie" and instead calls herself and her friends Band-Aids.

And that's where William's real odyssey begins. After attracting the attention of Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres (hilariously deadpan Terry Chen, in a series of deliciously godawful '70s print shirts), he's assigned to go out on the road with the up-and-coming Stillwater, chiefly to winnow out the personal secrets of the band's enigmatic guitarist, Russell (Billy Crudup). Russell holds William at arm's length, partly because he views him as "the enemy," but perhaps even more because, as the spare but heavily crosshatched shading of Crudup's performance reveals, there's not a whole lot to Russell beyond his basic likability. Russell is the stand-in for every meat-and-potatoes rock star out there who takes advantage of the benefits of success, probably without even thinking, even though he doesn't succumb to its very worst excesses. He's sensitive enough, yet perhaps not overly bright: At one point, fed up with conflicts within the band, he grabs William and heads out to find something "real," ending up at a house party with a group of awestruck Topeka, Kan., teens. After taking perhaps a tad too much acid, he ends up jumping off a roof into a swimming pool, but only after he has declared, "I am a golden god!"

William soaks it all in, but he has already begun to like Russell, which naturally causes conflicts when it's time to file his story. And he's not exempt from rock 'n' roll hedonism himself. Penny and her fellow Band-Aids (a group that includes terrific, if in this case underused, actors like Anna Paquin and magnificently scary Fairuza Balk) protect him on the road. But with the exception of Penny, who almost chastely excuses herself, they also ultimately deflower him in a hotel room, dancing around him in a swirl of chiffon scarves as he sits blankly on the bed in his BVDs, terrified and amused, his sunken adolescent chest looking more like a candidate for Vicks VapoRub than the erotic flutter of female hands.

The mad clutter of characters that flit through "Almost Famous" makes it, in the end, into a movie about lots of things: youthful dreams coming almost unbelievably true, journalistic integrity, both the scummy and the joyful sides of rock 'n' roll life in general and a fond but clear-eyed reminiscence of what rock 'n' roll was like in the early '70s. We're talking about the time before the movements that defined the decade and have long outlasted it (punk and disco), when a rock fan's record collection was likely to contain classics like "Rubber Soul" and "Blonde on Blonde" as well as soon-to-be classics like "The Allman Brothers Live at the Fillmore East" and "Led Zeppelin IV"; it was also likely to contain the progressive drivel of Yes, the sensitive singer-songwriter musings of Jackson Browne and, God help us, Cat Stevens -- even eccentric and now forgotten one-shots like Thunderclap Newman. (A number of these artists are represented on the movie's soundtrack.)

One of the movie's most affecting moments comes when a 12-year-old William pulls out the secret treasure that his sister (wide-eyed and expressive Zooey Deschanel), who has left home because she just can't deal with their mother, has bequeathed to him: It's a stash of old rock albums, from "Pet Sounds" to "Axis: Bold as Love," and William flips through them, now and then brushing his hand across an especially appealing cover. His life will change as of that first crackle and pop after the needle drops.

William might have discovered rock 'n' roll by listening to the bands his buddies liked, but it's a woman who introduces him to its joys. It's also a woman who tries, desperately, to keep him away from them, out of well-meaning but misguided protectiveness. William's mother, Elaine, a college professor, has clearly been feeding William's intelligence and curiosity all his life; you can't blame her for thinking rock 'n' roll is a lousy route to enlightenment, because she clearly just doesn't understand it. But as McDormand plays her, she's all quivering mother-hen anxiety, grounded, somehow, in the Socratic method. You can see how she's torn between having to accept that William has to find all the answers for himself and the conviction that he should be finding them her way. Her disappointment when he misses his own high school graduation is palpable, but her pride in his smarts, and her belief that he always has been and always will be a Good Boy, never wavers.

Patrick Fugit's William, with his button nose and mysterious kitty-cat smile, is eminently likable but ultimately a little opaque -- but that's the only honest way to play the character. Few people, at 15, are fully formed individuals, and William's psyche is an uneven landscape of reflective surfaces and highly absorbent ones. He's learning how to intelligently process the dazzle of the people around him, but he also can't help reveling in it, further magnifying their grandness by letting some of it bounce off him.

You might criticize Crowe for leaving William's character so undeveloped, but to me the choice seems baldly intentional. William sees the faults of his newfound friends -- he's too astute not to -- but he can't help liking them. That approach is practically Crowe's trademark as a director. In previous pictures like "Jerry Maguire" and "Say Anything ...," he made sure that we saw his characters' flaws, but his affection for them always shone through too. Maybe that's the kind of thing you learn from hanging out with rock stars at a young age.

It's telling, too, that "Almost Famous" contains a character whom Crowe seems to love even more than he does William: Penny Lane, played by Hudson with an intuitive lucidity that recalls the best work of her mother, Goldie Hawn. She's the figure who emerges from the movie with the most clarity. Then again, she also carries a measure of mystery usually reserved for the subjects of medieval ballads and poems based on Arthurian legend. Her physical beauty, defined by creamy skin and quivering gold ringlets, speaks of youthful rock royalty not yet gone -- and perhaps, with any luck, not ever going -- to seed.

I defy anyone who was young and tuned in to pop culture in the '70s not to bite his or her lip when Penny first struts onto the scene with her leggy walk and tailored fur-trimmed coat. She's the embodiment of the girl everyone wanted to sleep with or to be, a translucent princess who's nonetheless completely approachable and surprisingly grounded.

Penny is Russell's on-the-road girlfriend, an amusement for him while he's away from his old lady. The commonly used term for such young women, those eager to nestle into a star's orbit even for just the time it takes to blow him, is groupie. Almost everyone, even those who've never slept with one, has an opinion about them, from derision to a condescending kind of protectiveness. ("They just don't know what they're doing.") But in an interview in Premiere, Crowe noted that the ones he knew were "closer to the heart of rock 'n' roll than most of the musicians they slept with."

I think that's why Penny, and not William, is the soul of "Almost Famous," a dreams-made-flesh version not of the kind of girl who inspires rock songs but of the girls who fall so deeply in love with them that they confer a kind of nobility on their very existence. Of course, the '70s are now long past, and things are different; as a group, women are making more and better music than they ever have. But in the days before the Runaways, Poly Styrene, the Raincoats, L7 or Sleater-Kinney, most of us were by and large observers: That's simply a fact. Some of us wanted to get close to rock stars by sleeping with them. For those who did, the choice could be well-informed and positive or supremely ill-advised -- in other words, not much different from sleeping with regular guys.

Over the years acres and acres of feminist theory have been laid out to define the horrifying aspects of women's passivity in the rock arena. But those arguments are somehow insulting in themselves: Whoever said that just listening, really listening, is ever passive? A woman can be the subject of a song, its muse, its target, but she can also possess the very set of ears that completes it. The old (and unequivocally accurate) adage that boys form bands so they can get girls is proof of that truth in its roughest form. But the crude truth harbors a finer one: Rock 'n' roll, originally the province of men, needs women, or its existence means nothing.

Penny advises the other Band-Aids that the most important thing is never to take their liaisons too seriously. "If you ever get lonely, you go to the record store and you visit your friends," she advises them, an affirmation that, at least in theory, the music comes first. Of course, Penny loses sight of her own dictum: She falls devastatingly in love with Russell, who ends up treating her horribly. That opens a space for William, who of course has fallen in love with her, to come to her rescue.

But Penny, as Hudson plays her, is anything but a passive character. She may be ethereally unattainable, but she's also achingly real. In the scene where she learns exactly how Russell has betrayed her, she's backlighted with sunlight that shimmers through her diaphanous blouse and her halo of curls. She's dreamy all right, but the thing that stops her from being merely a vision of nostalgia is the bright flashes of pain you can read in her eyes -- if you make the effort to look there. She's the crushingly beautiful girl that you can see, or choose not to see. If you fail to look closely, it's your loss, not hers.

Crowe's vision of rock 'n' roll pulls all the usual elements -- loud guitars, cool guys, excess and debauchery -- into its orbit, but Penny Lane (who is, as the movie credits tell us, loosely based on a person Crowe knew in real life) represents the pleasure of the music in its purest form. And of course, if one were to pin a gender on the concept of pleasure, it could only be a "she." Everyone knows God modeled the phallus after the shape of a guitar. And that's just because she really dug the sound.

Shares