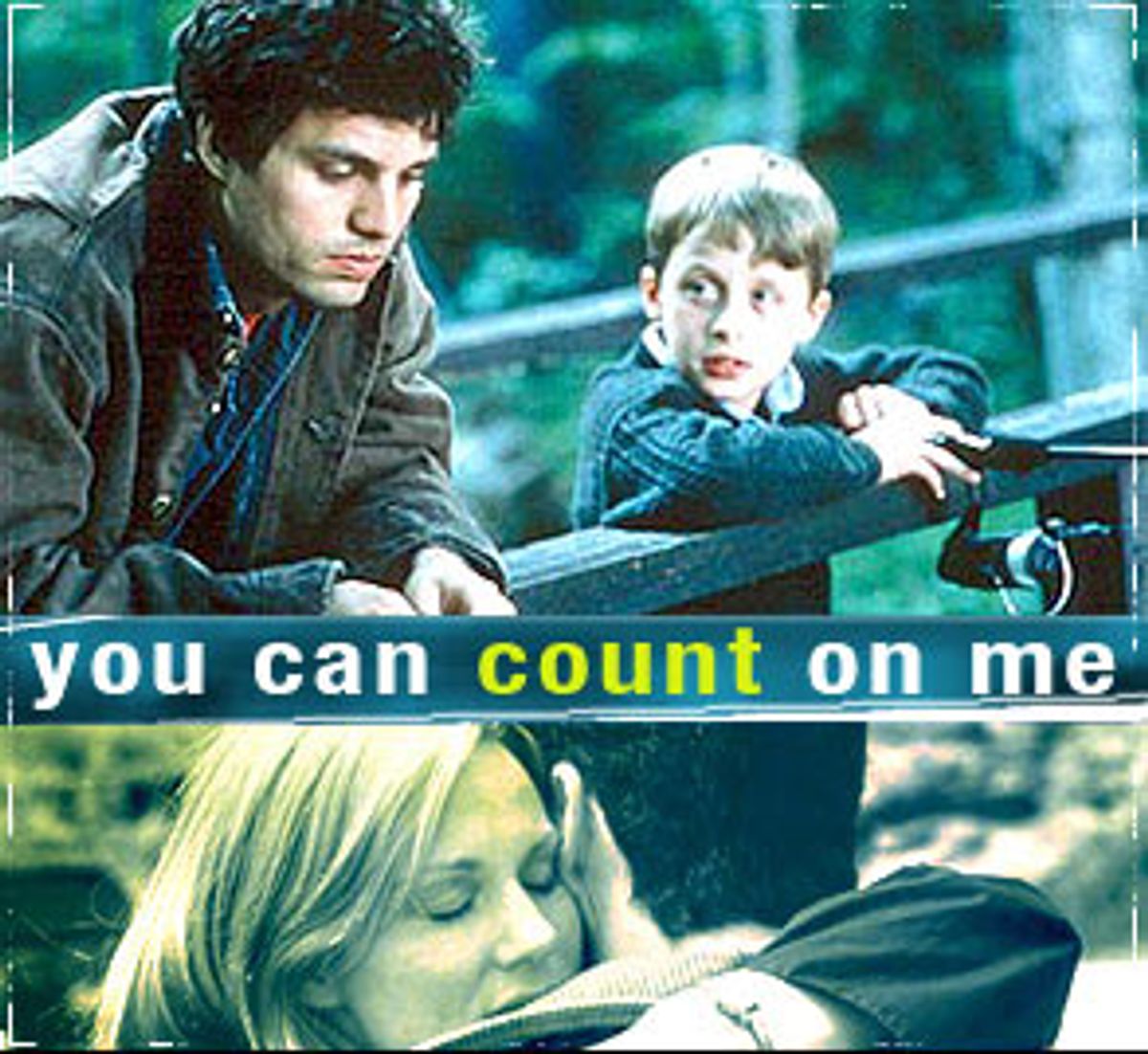

All the praise being heaped on "You Can Count on Me," the filmmaking debut of New York playwright Kenneth Lonergan, may say more about the tepid state of American cinema in 2000 than about this wry, modestly appealing small-town drama. Still, this is a subtle and often surprising study of the relationship between damaged adult siblings, full of mordant humor and dramatic invention. Lonergan has a terrific ear for dialogue and he understands that people don't shift course once or twice a lifetime but virtually every day, sometimes in the middle of a conversation. To my taste, his story goes off the rails in the last 20 minutes or so, but that happens in plenty of movies that are immensely more expensive and immeasurably worse than "You Can Count on Me."

If British theater has its own tradition of "kitchen-sink realism" -- quiet, dreary movies about working-class life -- American film has begun to specialize in what might be called Cheerios realism. These movies offer the kinds of challenges actors relish, depicting the lower fringes of middle-class existence on disordered sets laden with cereal boxes, bottles of Mrs. Butterworth's syrup, jars of French's mustard and so forth. This genre often intersects with the separate but related genre of stoner realism, in which characters fire up a doobie at every opportunity. "You Can Count on Me" certainly ranks highly on both the Grape Nuts and the ganja scales, although it may be difficult for any movie to top "Wonder Boys" in either category. (See also "Erin Brockovich," "American Beauty" and "The Slums of Beverly Hills," among others.)

Lonergan's direction in "You Can Count on Me" is clean and unshowy, and lets the characters drive the movie. He also tells a story in which things are not quite what they seem, and not in some dumb-ass thriller sense, either. His focal point, at least at first, is Sammy (Laura Linney), a single mom of 35 or so in Scottsville, an unassuming town in upstate New York. (Habitués of the Catskills region will recognize the picturesque main street of Margaretville, N.Y., as a principal location.) Scottsville is the kind of place where a local minister, played by Lonergan, won't even offer an unqualified opinion about adultery. "Well, it's a sin," he says. "But we try not to focus on that right off the bat."

Sammy's a slightly prissy, WASPy blond with a Lands' End wardrobe who works as a loan officer in a local bank. After sex with her on-again, off-again boyfriend Bob (Jon Tenney), she tells him, "Thanks for a lovely evening." She's not cracking a joke, or being a coquette. She's just being a nice PTA mom who is politely melting into middle age amid the pretty but unremarkable Scottsville scenery.

When her deadbeat, pothead brother Terry (Mark Ruffalo) turns up in town, Sammy is thrilled to see him. We, on the other hand, are less certain how to feel about this development. Before we even know who Terry is, we watch him in a crappy apartment with a sideways stereo speaker for a coffee table, telling an unidentified woman, "I am not the kind of guy that everyone says I am." People who feel the need to say that are generally wrong. Since Terry gets madly stoned in the bathroom of a moving bus, and asks Sammy for money almost as soon as he sees her, we feel justified in suspecting that he's exactly that kind of guy.

But everything in this strikingly grown-up little movie is up for grabs, including what we think we know about Sammy, Terry and the title itself. At first I assumed that Lonergan means the name of the film to be sadly ironic; "You can count on me" is the kind of thing dissolute, handsome Terry is always saying while his eyes dart around the room in a troubled one-two-three-four cadence, unable to look at Sammy directly. As we gradually piece together (with the help of Lonergan's eerie, almost wordless prologue), Terry and Sammy were orphaned as children and grew up unusually close. They do indeed count on each other, even if they don't always know for what and if the relationship rarely runs smoothly.

As horrified as Sammy is by Terry's news that he's dead broke and has recently been in jail in Florida, his arrival is exactly the spark she needs to knock her life out of its deepening groove of order and rectitude. She's being tormented by a nit-picking boss (Matthew Broderick, wonderful in a small but crucial role) who has set himself a "personal challenge" to raise the standard of banking in Scottsville, and imprisoned by Bob's lukewarm affections.

A delicate-featured blond with something of Meryl Streep's regal bearing, Linney is an accomplished stage actress who has never quite gotten the right break in movies. She won't exactly knock your socks off here, but her performance as a woman who has almost accidentally developed a sudden savor for life is full of delicious moments. When Terry asks her if she wants to smoke some pot, she responds immediately, with a tone of offended certainty: "No, I don't." Then, a second later, she's his sister again: "Why, you got some?"

Terry, on the other hand, when asked to take care of his 9-year-old nephew, Rudy (Rory Culkin, the latest of his clan to break into movies), displays a surprising ease and maturity. Sammy rushes out of work one day when the baby sitter calls to say that Rudy hasn't turned up, only to find that Terry has brought him to a construction site and is teaching him how to hammer nails. He understands immediately that an uncle's role is to provide things a parent can't: post-curfew games of pool, frank late-night conversations. (Rudy: "Why are you smoking?" Terry: "Um, because it's bad. Don't ever do it.")

If there's a revelation in this cast, it's Ruffalo, who plays Terry as a peculiar mix of masculinity and vulnerability; his life is a mess, but at least he's not lying to himself about it. "I realize that I'm in no position to say anything ever," he tells Sammy during a quarrel, yet he seems mortally wounded when she wants to hire a plumber rather than allowing him to rip the house apart. Terry may be drifting through life, fatally unmoored, but he's the only person who suspects that Sammy is too, after her own fashion.

After Bob asks Sammy to marry him, she immediately embarks on a hilariously ill-advised affair with the stick-up-the-butt Broderick character, and at virtually the same time asks the preacher played by Lonergan to help convince Terry that life is important. (Talk about authorial intervention.) All of this plays out enjoyably enough; it's only when Terry and Rudy embark on a quest to find Rudy Sr., the kid's missing and mysterious father, that Lonergan seems to violate the terms of his own story. For the first time, "You Can Count on Me" seems like forced melodrama, in which some (relatively) cataclysmic event must occur to bring the story to a climax. Thankfully, it's a minor blemish on this fundamentally sympathetic minor-key fable of love and loss in America.

Shares