"Before Night Falls" is such a vivid experience that it holds you fully in each moment. Even if you've read the memoir of the Cuban novelist and poet Reinaldo Arenas on which the film is based, from scene to scene there's no telling how painter-turned-director Julian Schnabel, or his wonderful star, Javier Bardem, will tackle what comes next. "Feverish" has been the word used to describe the movie in many of its reviews. But in confidence and sensuality "Before Night Falls" suggests the calm that can come with fever, that heightened and slowed state of awareness where each perception and sensation takes on a vibrant clarity.

The movie isn't always a model of clarity. Schnabel immerses us in the atmosphere before giving us our bearings and he doesn't always identify the characters or their relation to each other. But the occasional confusions are a small price to pay for a director who places enough trust in his audience's intelligence to not spell everything out for them, to work allusively rather than declaratively to convey the meanings of Reinaldo Arenas' life.

Born in 1943, Arenas came of age during Castro's revolution, even running away to join the rebels (though he saw no action). But after Castro came to power, the show trials and the executions with no trials of any kind, the "People's Farms" that were not allowed to provide food to starving citizens, the political and intellectual purges, gradually convinced Arenas that Cuba had merely traded one dictatorship for another. It was Arenas' homosexuality and what the government deemed the "counterrevolutionary" tenor of his novels (many were published abroad after being smuggled out) that resulted in years of persecution and finally a stint in one of Castro's prisons. When Castro expelled the "riffraff" during the 1980 Mariel boat lifts, Arenas, who was on a list of people forbidden to leave, escaped by changing the name on his passport. Settling in New York, he taught, wrote and lectured until, in the final stages of AIDS, he took his life in 1990.

Arenas began his memoir "Before Night Falls" before escaping from Cuba and completed it in New York. Its title refers to the daylight he had in which to write while hiding out from the police in the woods. It is a great book, in which the excitement of intellectual and sexual coming-of-age is both thwarted and intensified by the political repression that threatens to end them both. There's a touch of gay machismo swaggering through Arenas' prose; every trip to the beach, every bus ride, even a simple request for a light from a stranger on the street is an excuse for sex. Mixing Arenas' randiness with his rage toward Castro, the book reads like a combination of Joe Orton's diaries and George Orwell's "Homage to Catalonia."

In part an act of revenge, the memoir is not always generous. Arenas delights in outing people who moved on to high positions in Castro's regime, and he has no time for the writers like Gabriel García Márquez and Eduardo Galeano, who he despises for siding with Castro. It would take an inhuman capacity for forgiveness for a writer who carried on his work in the face of real repression to excuse those who lied about or excused that repression.

Experience always confounds ideology, and after his escape Arenas became somewhat of an inconvenience. The left, always ready to embrace a persecuted writer, didn't know what to do with one who shattered any illusions they harbored about Castro being a benevolent dictator. (It certainly didn't help Arenas that in the Reagan years, simply insisting on the reality of life under communism was enough to get you accused of siding with Reagan's simplistic jingoism.) At a Harvard reception, a German professor, his plate piled high with food, told Arenas that he believed Castro had done great things for Cuba. After informing the academic that, in Cuba, only government officials could eat so well, Arenas threw the man's plate against the wall. The book suggests the toll that bitterness took on Arenas.

In his lovely memoir of Arenas in the book "Eminent Maricones," the novelist, poet and critic Jaime Manrique talked of "the truly Dostoyevskian side to [Arenas'] nature." Once, in a fit of rage, he said to Manrique, "There is no way on earth I can forget what I went through. It's my duty to remember. This will not be over until Castro is dead. Or I am dead."

Working from a screenplay he adapted with Lázaro Gomes Carriles and Cunningham O'Keefe, Schnabel has wisely chosen to treat the book, crammed as it is with people and incidents, as a picaresque. Without sacrificing the weight of events, Schnabel maintains a light touch. The film moves fleetly from Arenas' childhood and adolescence, to his emergence as a young writer and voracious cruiser, to his years in prison and his escape to New York. Schnabel doesn't go into the book's detail about the brutality Arenas encountered in prison and that's just as well (it might overwhelm the rest of the movie). But he keeps faith with that experience in another way: by using the restless momentum of the narrative to suggest both the exuberance with which Arenas lived his life and the brevity of the time in which he could get away with his acts of literary and erotic rebellion.

For Arenas, there's always a new book to read or write, and always new lovers to be sampled, even a group of Castro's soldiers who, in one scene, approach Arenas and his friends menacingly before giving themselves over to a naked campfire bacchanal that suggests kids at play as much as erotic abandon. At times, Javier Bardem's heavy-lidded eyes suggest a man who has done away with the need for sleep because there's simply too much going on. "All affirmations of life are diametrically opposed to dogmatic regimes," Arenas wrote in his memoir, and Schnabel suggests how as Castro's revolutionary state became more repressive, it inadvertently fed dissent. Even in a Communist dictatorship, this was the '60s, with all the sexual adventurism of the times.

In all the arts, but especially movies, pleasure is the enemy of schoolmarmish instruction and that seems to be Schnabel's dictum here. When Arenas meets the Cuban writer José Lezama Lima (Manuel Gonzalez), he tells him that beauty is the natural enemy of dictatorships because it opens realms of feeling that dictatorships deny. With his cinematographers Xavier Peréz Grobet and Guillermo Rosas, Schanbel turns Cuba into such a lush-looking place that he makes the repression seem like something of a violation of the natural order. In the opening scene, green trees swaying overhead appear to melt into each other, as if the visions of loveliness Cuba has to offer are fleeting, transitory, there for those with the eyes to see them and the quickness to retain them. The way Schnabel and his hero see the island becomes a form of visual music, and like the music in "Buena Vista Social Club," an expression of fullness and vitality. The grayness of the final scenes set in New York (when Arenas is dying of AIDS) are a letdown. But they get at the contradiction of how an artist longing for freedom may flourish more when he's struggling for it than when he has it.

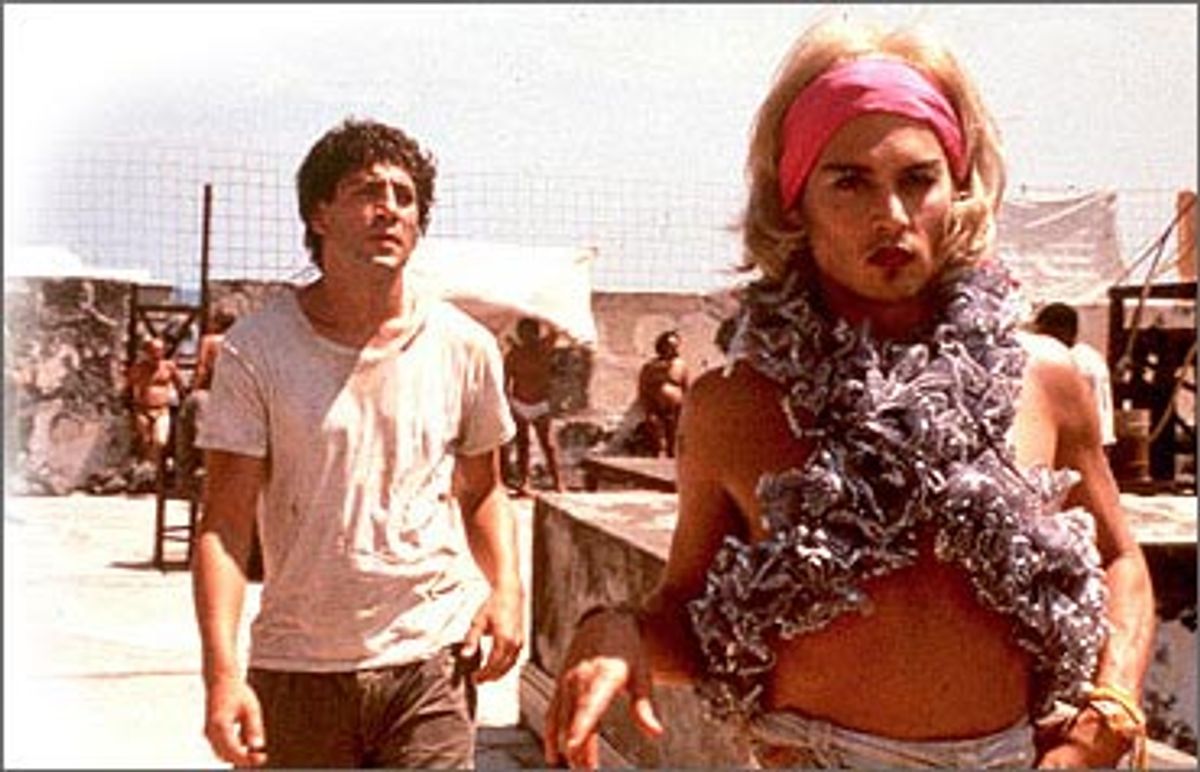

What the movie is missing is a sense of humor and, most of all, sexual exuberance. There are some good jokes, like Johnny Depp (who also turns up -- looking fabulous -- as a transvestite) playing a prison interrogator who can't resist stroking himself as he regards a portrait of Castro, and a quick scene where Arenas uses an underwater mask to check out the packages of various male swimmers. But Schnabel doesn't match the mixture of delicacy and rut in Arenas' descriptions of his erotic encounters. He's a hustler with the expressive gifts of a voluptuary. The movie could have used some of the effrontery of Almodóvar's first films in which the death of Franco was the excuse for everyone's libido to go sky-high. The threat of exposure gives Arenas' sex life an added charge, but it's a charge the movie gets only fitfully.

Still, Schnabel has managed to avoid nearly every cliché of the tortured artist. This is only his second movie, after "Basquiat," but he has a command of technique that would be impressive in more seasoned directors. He seizes on images from the memoir and uses them almost as archetypes, as when the young Reinaldo dreamily comes upon a group of naked men bathing and happily splashing each other in the river. Even when he gives us a scene familiar from other movies, like the one where Reinaldo's teacher visits his grandfather's farm and tells them the boy has the sensitivity of a poet, he ends with something we haven't seen before. Silently taking in the teacher's declaration, the old men suddenly erupts in a scream of fury before grabbing an ax and dragging the boy into the yard where he chops down a tree in which Reinaldo has carved a poem in the bark. There's no sentimentality about the land or the people in the scene.

As good as it is, "Before Night Falls" might not work if Schnabel hadn't found a leading man to hold it together and the Spanish actor Javier Bardem has the understated charisma to pull it off. With his big build, curly dark hair and Roman nose, Bardem at times suggests a beefy Adam Arkin. Yet there's something tender about his reserves of humor and especially in the way he seems to caress his words when he speaks. Movie heroes who appear to have no trouble making sacrifices of conscience are always a little alienating; they make the rest of us feel like pikers. Bardem lets us see the fear in Arenas and that humanizes him. Instead of steely reserve, he gives us a flicker of defiant pride, but never without the apprehension that those displays of character are going to cost.

Both Schnabel and Bardem are into the sweaty joy of creation rather than the flossy prostration before the altar of culture that so often accompanies movies about the lives of artists. Remarking on the photos in the New York Times of Schnabel celebrating the movie's premiere in a party at his loft, a friend of mine said the neo-expressionist painter looks exactly like the movie he's made. With his hair and beard sticking out at all angles, his gut hanging out of his rumpled clothes, wet with the sweat of dancing to a Cuban band, Schnabel was the artist as rotund satyr. At its best "Before Night Falls" has the same grubby, masculine exultation of someone comfortable with the dirt under his fingernails and still capable of being enchanted by the melancholy of loss wafting in from some overheard tune.

Shares