“Monkeybone” is a giddy madcap classic, one of the wildest and funniest American comedies in years. Remember those “Test Your Strength” contraptions where you swing a mallet to ring the bell up top? “Monkeybone” made me feel like the weight. I felt like I was zinging out of my chair with laughter.

Unfortunately, Twentieth Century Fox is doing what it can to keep the movie under wraps. After the film was finished, it was subjected to multiple testings. Then, the studio boss who had greenlighted the picture stepped down from his position and the film was tested some more. Finally, it was ordered to be recut.

None of these hassles are radically unusual, but in the context of what would happen later, all of the steps are portentous. Next the film was bumped from a prestigious November opening into the February ghetto. And now the trouble is with the marketing. Except for New York and Los Angeles, there were reportedly no ads in last Sunday’s papers. So if you live in most of the country and haven’t caught any of the TV spots, you won’t even know the movie is opening.

There may not be much most critics can do to alert potential audiences. Fox didn’t screen the movie for New York critics until Wednesday night, about a day and a half before the opening. This guarantees that the weeklies won’t get to cover the movie before the all-important opening weekend, and that most daily critics will have limited time and space to meet their Friday deadline. This is the strategy that the studios use when they have no faith in a movie and do everything they can to try and make it look like a bomb. As Pauline Kael once wrote, “Mediocrity and stupidity certainly don’t scare them; talent does.” By that standard, “Monkeybone” must have had the brain trust at Fox shitting in their Helmut Langs.

The primary source for Sam Hamm’s script is Kaja Blackley’s graphic novel “Dark Town,” but he and director Henry Selick (who also directed “Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas”) have borrowed from cheesy Saturday afternoon horror movies, comic books, model kits of cars and monsters, German expressionism, surrealist art, postcard art, the google-eyed monster hot-rodders of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, childhood memories of amusement parks and kiddie bad dreams and the sort of cheerfully crude kid’s humor that slips out like an unexpected fart. “Monkeybone” tosses pop trash, the dream logic so beloved of the surrealists and the homegrown dada familiar from the wilder reaches of American comedy (W.C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, Robert Crumb) into a Waring blender and pours out a spiked smoothie, an artist’s neurotic fantasy of being taken over by his creation.

Brendan Fraser plays a cartoonist named Stu Miley (the name tag on his slacker cool mechanic’s jacket reads S.Miley — get it?) who, when we first meet him, is doing his best to hide behind his forelock. His comic series “Monkeybone” has been picked up by a network, Stu is wary of the 15 minutes the media moguls are affording him, and his schmooze-hound agent (David Foley) is fielding any merchandising offer he can get his hands on. All Stu wants is to slip away with his girlfriend Julie (Bridget Fonda) to their cozy, cluttered little cottage where he’s ready to pop the question.

They never make it. A car accident leaves Stu in a coma. While his body vegetates in a hospital bed, his soul winds up in Downtown — Purgatory as a sort of noir theme park. The inhabitants are straight out of Stu’s childhood nightmares: a Cyclops figure who’s all head; carnivorous looking piggies running barbecue stands; Siamese devil triplets in satiny powder-blue tuxes; a floating Abe Lincoln head that materializes in the sky. Everybody knows Stu. Downtown grooves on the nightmares of people on Earth, which play in a local theater — the Morpheum. In a comic riff on how the public digs what artists suffer to produce, Stu has provided the locals with some of the funkiest they’ve ever seen.

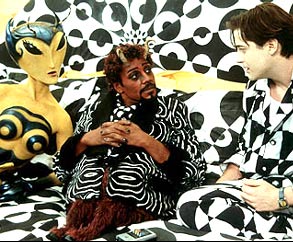

None of Stu’s past night terrors quite compare to the nightmare he lives out while residing in Downtown. It seems that Monkeybone himself, the loudmouthed cartoon chimp who serves as Stu’s id (particularly his sexual id) is a big star at the local Coma Bar. With a voice provided by John Turturro, the puppet is one sleazy lounge lizard, and Stu is stuck. Just like Visa, Monkeybone is everywhere Stu wants to be. When Stu tries to have a quiet drink, Monkeybone is there on stage performing one of his bits. When Stu craves a cozy word with the purr-fectly adorable barmaid Kitty (the luscious Rose McGowan, a cunning little pussycat in whiskers and tail), Monkeybone’s tongue drops into Stu’s drink as pink and unwelcome as a dog’s boner. And when Stu determines how to sneak his way back to Earth and his beloved Julie, Monkeybone senses his chance to take over his creator.

The plot of “Monkeybone” doesn’t always make literal sense. (At one point Stu winds up sharing a cell with the likes of Jack the Ripper, Edgar Allen Poe, Attila the Hun, Typhoid Mary, Lizzie Borden and Stephen King. I wasn’t sure why — but it didn’t keep me from laughing when King requests a night light and Poe calls him a “pussy.”) But the spirit and look of the film never falter and that’s what gives it coherence.

Bill Boes’ production design and Andrew Dunn’s cinematography are frequently flabbergasting. They’ve created a nightmare comic strip world that’s half Gothic horror, half tiki lounge. You seem to see things out of the corner of your eye — like what appears to be a midget child in a tux. There are stunning shots of the comatose Stu deflating like a balloon or being absorbed into one of his drawings.

As Stu slips into a coma he descends into his hospital stretcher until Julie is hovering above him as if she were calling down from the top of a cliff. When Fraser appears in a black-and-white fantasy sequence, he’s been given the sallow makeup and wild dark, shadowed eyes of creepy crawly Dwight Frye, the fly-eating Renfield of the Bela Lugosi “Dracula.” There are grim reapers in intricately folded shrouds that look as if Issey Miyake has gone into designing Halloween costumes.

The details and jokes pile up, zip and ping through the background with the suddenness of the sound effects in a Looney Tune. Nothing seems too wild for the filmmakers to try. Often, before you can laugh, you have to pause for a millisecond and register the outrageousness of what you’re seeing. From now on, when your dog whimpers and shakes in his sleep, you’ll have nothing but sympathy for his nightmares.

The first half of the movie is such a sustained feat of imaginatively ghoulish wit that when Monkeybone returns to Earth, waking Stu from his coma and taking over his body, I kept waiting for the movie to go splat. That it doesn’t is a tribute to both Hamm and Selick’s sure fix on their material and also to Brendan Fraser. There’s always been something vaguely simian about Fraser, maybe just the suggestion of a stoop in his broad-shouldered gait. He’s a sweet, sleepy, doe-eyed galoot but he has never cut loose the way he does here. As the Monkeybone-possessed Stu, Fraser pulls off shambling bits of knockabout physical comedy, scurrying under his piano instead of walking around it, turning the four-poster Stu shares with Julie into a jungle gym for some acrobatic foreplay. Fraser as Monkeybone is more of a show than Monkeybone on his own, a horny little chimp in King Kong’s body.

Artists often say their characters take up residence in their head. Hamm and Selick treat that notion literally, turning Monkeybone’s possession of Stu into a comic-book metaphor for the way success breeds monsters. Stu becomes his character’s butt monkey. With Monkeybone at the controls, the once ambivalent Stu is suddenly transformed into the perfect media whore, agreeing to any merchandising scheme that comes along, especially the one that will allow Monkeybone to feed Downtown with a whole new batch of the nightmares they crave.

It was easy to assign Tim Burton the credit for “The Nightmare Before Christmas” and assume Henry Selick’s directing credit was just a supervisory role. That seemed confirmed by Selick’s somewhat icky musical version of “James and the Giant Peach.” But maybe he was just waiting for material on which he could put his stamp. Whatever the reason, “Monkeybone” is a dazzling piece of go-for-broke direction. Burton’s influence is still palpable (Downtown has some of the feel of the hereafter waiting room in “Beetlejuice”) but Selick’s work is looser, less polished, and that works in the movie’s favor.

If the rough patches in “Monkeybone” were smoothed out (especially if the faked backgrounds of some shots were less obvious) the movie might have been aesthetically more pleasing — and not as funny. The slight messiness keeps the insanely detailed design from seeming too fussy. For all its extravagance, “Monkeybone” has some of the relaxed tone of Paramount’s modest 1930s comedies. The production isn’t top heavy so there’s nothing to rein the nuttiness in.

Selick is lucky to be working with a screenwriter who can get right to the essence of a comic-book universe. Sam Hamm, who worked on the script for Burton’s rhapsodic “Batman” (and also wrote one of the best stories for the Batman comic book “Blind Justice”), doesn’t indulge in nerd comic-book worship. He loves comics for the pop metaphors they provide, and he serves up those metaphors without falsifying why we enjoy them, without depriving them of their energy. Hamm’s gags are rude, almost extreme; Monkeybone himself is essentially an unruly, inconvenient phallus. But the tone of “Monkeybone” is a neat blend of the sweet (Julie, coming back from the hospital after Stu has gone into coma, to discover the Rube Goldberg-style contraption Stu has devised to propose to her) and the perverse (the gag that serves as Rose McGowan’s final bow).

“Monkeybone” begs for actors game enough to trust the creators and luckily, it has them. Bridget Fonda’s role is a little too much “the girlfriend” but her presence is enough. She must be the most ravishing ray of sunshine in the movies. The movie’s crazy quotient rockets even higher in the scenes with Chris Kattan as an Olympic gymnast with a broken neck who’s brought back to life (don’t ask). Kattan flounces through his scenes in red tights as his neck flops to the side like a choked chicken’s. He’s like one of the zombies from “Night of the Living Dead” risen from the grave as a rag doll. Kattan has been given the most outrageous gags in the movie and each one scores. And as if he weren’t enough, Hamm and Selick add a fillip: a group of doctors in red smocks — the Keystone Coroners — chasing him down to harvest his organs. I honestly don’t know the last time I’ve laughed so hard for so long at a movie sequence. Kattan’s scenes are one great sick joke that just gets sicker and funnier as it goes on.

Even if “Monkeybone” could count on studio support, a comic-book movie aimed at grown-ups is always a tough sell. Adults seeing the ads or hearing the title may assume it’s juvenile junk and stay away. And though kids may get some laughs, it’s really not directed at them. The sources of the movie’s humor are comic books and scatological jokes. But the subject is sexual anxiety, career anxiety, the enticements of freedom vs. the pleasures of commitment, the tradeoffs you make for success and the question of how much of yourself you should put into your work.

Whether or not Twentieth Century Fox’s plan to make sure “Monkeybone” is dead on arrival at the box office succeeds, the movie is going to have a life beyond its commercial run. They’ll be the usual voices willing to follow the studio’s lead (those critics are rather like the uncles Dylan Thomas said always showed up at Christmas time, “the same uncles”), and there may well be a band of passionate fans who get on the movie’s wavelength. Either way, for the next few weeks you have a chance to see one of the most inventive American comedies in years on the big screen. This is one monkey you want on your back.