"61*," about the 1961 home run race between Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, isn't quite as good as I think it is. You should probably know that before reading any further. Billy Crystal, who conceived and directed the HBO movie, has shrewdly selected a subject that I can't keep my emotional distance from. Neither, I suspect, will a large portion of the film's audience. But why bother trying? It's a baseball movie, maybe the best one since Ron Shelton's "Bull Durham."

The real story is so perfect it requires no embellishment, and Crystal doesn't give it any. Mickey Mantle (Thomas Jane), 30, a blond god at the height of his power (Mantle had won two Most Valuable Player awards and five World Series rings going into the 1961 season) and popularity is confronted by the first challenge to his sovereignty on the Yankees: another blond god named Roger Maris (Barry Pepper) who beat out Mantle for the MVP award in his first year on the team, 1960. The next year, spurred on (and in large part aided) by the other man's presence in the lineup, the two made an unprecedented assault on the most sacred record in baseball: Babe Ruth's single-season record of 60 home runs.

Mantle, hobbled by injuries and by an addiction to the high life, eventually falters and watches from the sidelines as Maris endures an unprecedented media blitz and lurches toward the record.

As he does, an amazing thing happens: Mickey Mantle matures. This seems like the stuff of which sports movies are made, but by all accounts that is exactly the way it happened. Mantle, a miner's son from Oklahoma, was pushed hard into baseball as an alternative to the mines. No male in his family had lived to see age 40 in at least two generations and Mantle believed he wouldn't make it either, so his private life became a sex-, alcohol- and painkiller-drenched self-fulfilling prophecy.

The arrival of Roger Maris, raised in Fargo, N.D., and happily playing right field for the Kansas City Athletics before the Yankees traded for him, took part of the spotlight and then much of the pressure off Mantle; the overgrown man-child who smashed water coolers when he struck out was exorcised. Meanwhile, Maris' problems had only begun. Besieged by an unwanted press and berated by fans as unworthy of comparison with Ruth and Mantle, Maris took to smoking six packs of cigarettes a day -- he would die of cancer at 51 -- and his hair fell out in clumps.

Crystal the director doesn't have to do much more to this story than tell it well, and he does, with an able assist from Haskell Wexler's video-tinged cinematography, which evokes the look of how most of us remember the events of '61. (I was too young to really understand baseball rules or strategy, but when I watched the replays of the home runs on the evening news I knew that something momentous was happening.)

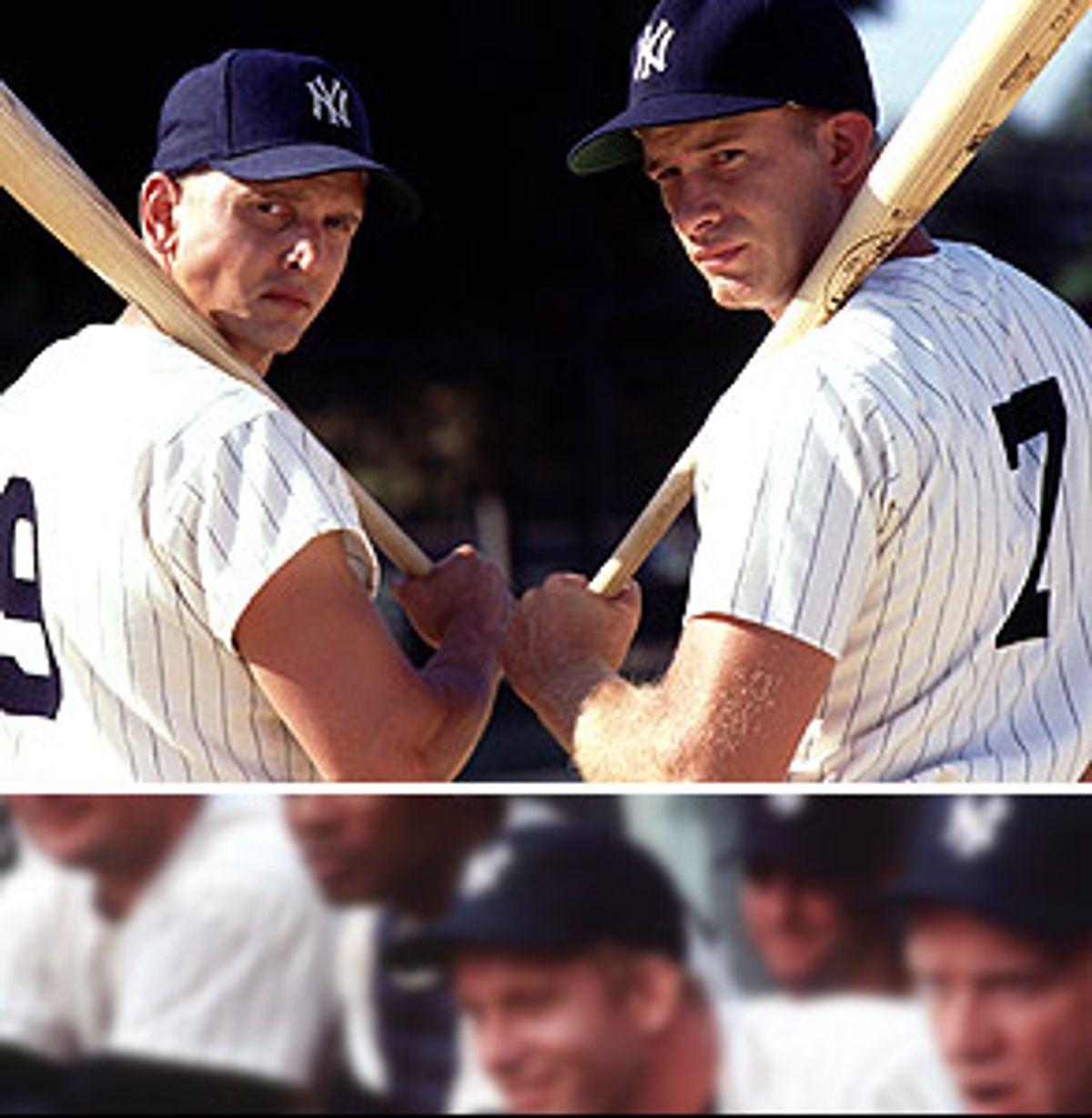

And Crystal has been lucky beyond reason in his casting. The two relative unknowns, Barry Pepper and Thomas Jane, bear an uncanny resemblance to Maris and Mantle -- and they run and throw and swing like them. In and of itself this might be of little importance. What does matter, to viewers who never saw Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, is that the actors, once they take the field, be able to suggest to us why these men were idols in the first place. Jane, heavily muscled and broad-shouldered, perfectly replicates Mantle's powerful lunge at the ball from either side of the plate -- I do hope they aren't fooling us here with trick photography -- and Pepper has created a duplicate to Maris' famous whiplash stroke that lifted the ball into Yankee Stadium's friendly right-field stands. Where did they find these guys?

Jane and Pepper are so good they are able to suggest the loneliness of the long-distance swingers that the script can only hint at. "You don't know shit about me," bellows Jane's Mantle; "Yeah, fine," snarls Pepper's sullen Maris, who bangs on walls to release pent-up emotion. "This is your one shot to show 'em what you're made of," says a repentant Mantle. These are men of few words, you think, because they only seem to know a few.

But, then, there would be something false about a Mantle and Maris articulate enough to express what was going on in their heads in 1961. The skill with which Jane's shrewd country boy finesses the city-slicker New York press, or the way he flips his cap, boyish grin angled perfectly toward the camera, tells us more about Mickey Mantle than words could. A shot of Pepper alone in his locker, staring wistfully into space after Maris breaks the record, unable to comprehend what he has just done, says more about the pressure of unwanted celebrity than any speech ever has.

Maybe you had to have been there to really appreciate "61*." On the other hand, "61*" might just make you feel as if you were.

Shares