HBO has done some extraordinary things over the last few years in the area of sports documentary -- if they ever establish an HBO Sports Film Library I'll be the first to join. But the upcoming "Ali-Frazier I: One Nation ... Divisible," which debuts Thursday, is on a whole new level. With all due respect to the much-honored documentary about the Ali-Foreman fight, "When We Were Kings," "One Nation ... Divisible" has the best subject for a boxing film imaginable: the social, political and personal turmoil that swirled around the first-ever meeting of two undefeated men who both claimed the heavyweight championship.

Actually, the social and political ends have been handled fairly well in print over the years, starting with Norman Mailer's seminal essay "King of the Hill," published in 1971, a few months after the March 8 fight, on up to the recent "Muhammad Ali Reader" and David Remnick's "King of the World," though we can all do with seeing some actual films of anti-war demonstrators and draft demonstrations again. What is unique in "One Nation ... Divisible" is how it makes clear the degree to which the personal relationships between Ali and Joe Frazier propelled the fight into what one of the on-screen commentators calls, and for once without hyperbole, "The greatest sporting event of the 20th century."

But for the politics of Vietnam (embodied in Ali's refusal to be inducted into the Army) and race, the truth is we would not remember the fight today if Ali had caved in early, or if he had stopped Frazier on cuts in, say, the fifth round. Yes, we remember the fight because of the politics, but watching "One Nation ... Divisible" I realized we also remember the politics -- or at least I can now discuss them with the younger kids in my family -- because they led to a great fight.

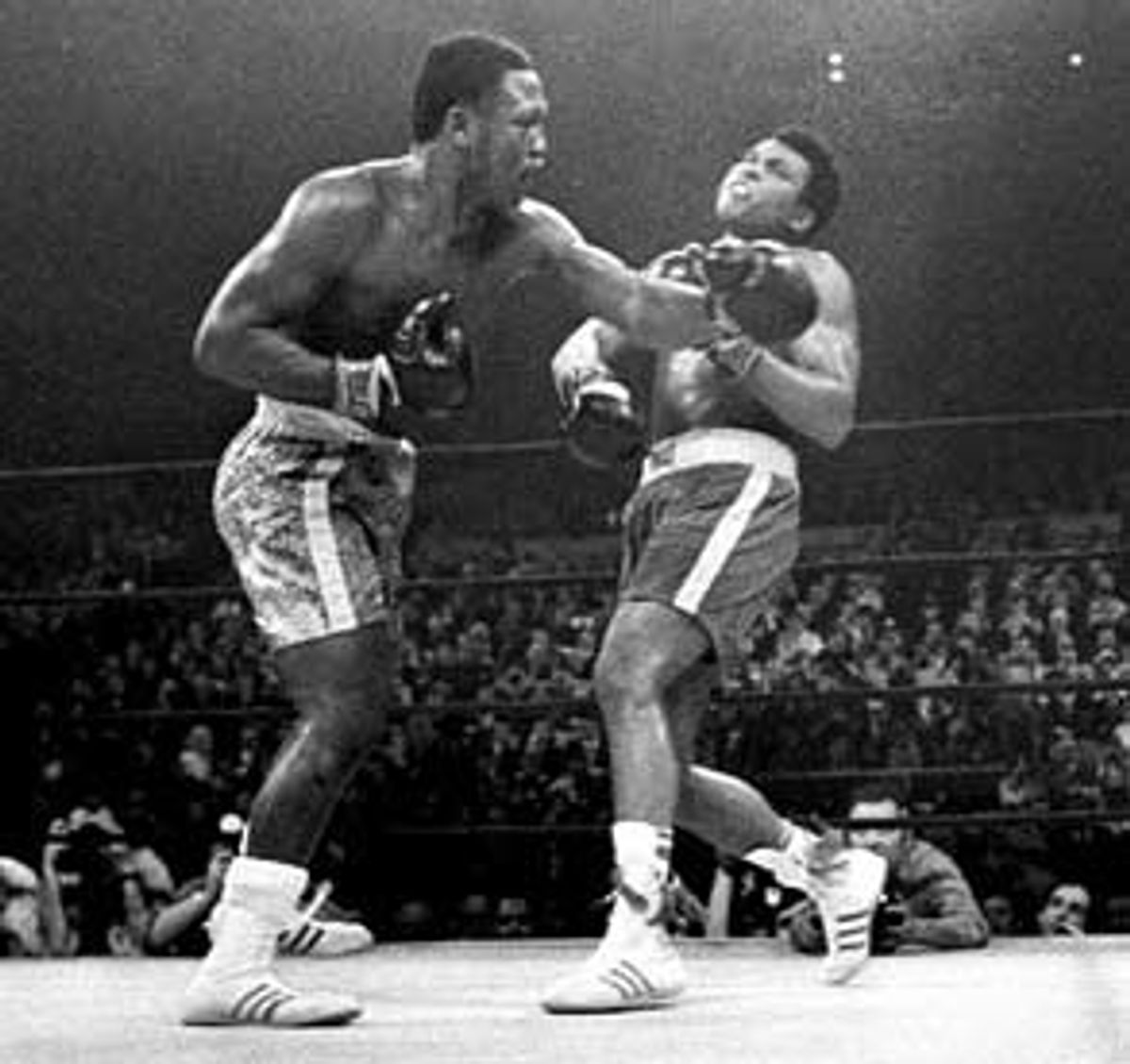

And, as the highlights at the end of the film make clear, it was a great fight, the greatest heavyweight championship fight of all time. Never before had two big (well over 200 pounds) men this skilled and determined, both with claims on the heavyweight title, fought so hard for so long. I've watched all the tapes of great fighters -- Dempsey and Tunney were one-sided except for the brief excitement of the "long count" in the second bout; Joe Louis and Billy Conn was great only because an overmatched light heavyweight fought over his head; and Jersey Joe Walcott and Rocky Marciano was fought by much smaller men.

Ali-Frazier could never happen again. For one thing, it went 15 full rounds, and title fights today are 12 rounds. For another, there's the competing alphabet title holders. Ali and Frazier didn't just claim the title belt of a particular political organization; because of Ali's three-and-a-half-year layoff and subsequent court battles, by 1971 he and Frazier had equally good claims to all belts from all organizations.

What "One Nation ... Divisible" makes brutally clear is the degree to which such a highly charged political event was animated by personal animosity. Or, more correctly, by what one of the two men regarded as betrayal. It has long been known that Ali and Frazier were friends before the pre-fight publicity barrage began, but no one brought the point home by talking to the fighters (or, in this case, the fighter, since Ali is in no shape to talk) about this. Frazier had volunteered his support to Ali when the U.S. government blocked his moves to get back in the ring. Frazier told him, "Whatever it takes, I'll help," and at one point gave him $2,000 to pay his hotel bills when Ali was down on his luck.

But when Ali began to campaign for the only big money fight out there -- Frazier -- he ignored Frazier the man and began pummeling the object. Frazier became an "Uncle Tom" and "The White Man's Champion" -- which was certainly true to a certain extent, but became all the more so because Ali made it so. Frazier, who had picked cotton as a boy in South Carolina and who dropped out of school to butcher meat in Philadelphia, had lived a life far closer to that of most American blacks than the relatively sheltered, middle-class Ali. All of a sudden, in the words of one of Ali's biographers, Frazier "became a symbol of Ali's oppressors."

One simply can't write off Ali's behavior as an attempt to sell tickets. The open cruelty of Ali's campaign (mocking Frazier's speech and flattening his nose to look like Frazier's) has never been fully acknowledged by his many biographers and admirers. Frazier clearly envied Ali; is it possible Ali was jealous of Frazier, jealous that he had actually lived the life of oppression that Ali didn't begin to discover until he was a teenager and found out what segregation meant?

Muhammad Ali is the most written-about sports figure who ever lived, but as "One Nation ... Divisible" makes clear, we don't entirely know him yet.

Shares