The big problem with "Monster's Ball" is that you have to sit through the first half to get to the second. It's a movie that rewards patience for all the wrong reasons: The first half, plodding, excruciatingly deliberate and slow-moving, is the sort of thing that makes the audience suffer for a director's good intentions. But the second half of "Monster's Ball" feels like a different picture altogether. The director, Marc Forster, seems to relax his grip not just on his actors but on his own rigid lesson plan, and the movie starts to breathe.

A family saga set in present-day Georgia, "Monster's Ball" uses the most thuddingly obvious tools to educate us about the insidious evils of racism, bigotry, misogyny, bad parenting and, it seems, simply having the bad luck to have been born and brought up in the rural South. Hank Grotowski (Billy Bob Thornton -- looking shockingly underfed, despite the chocolate ice cream his character keeps scarfing) is a cold and taciturn corrections officer who lives with his malevolently cantankerous and openly racist father, Buck (Peter Boyle), and his son Sonny (Heath Ledger).

Buck, now retired, had been a corrections officer as well; Sonny has also entered this not-so-proud line of work, but, because he's a much more caring soul than either his father or grandfather, he's lousy at it. When he's called upon to assist in the execution of a convict (played with leaden hamminess by Sean "P. Diddy" Combs), he botches it, angering his father, who barely speaks to him anyway. We're made to think that Hank has absorbed all of Buck's bad qualities deep into his bones, not because he's intrinsically bad but because it's never occurred to him to resist.

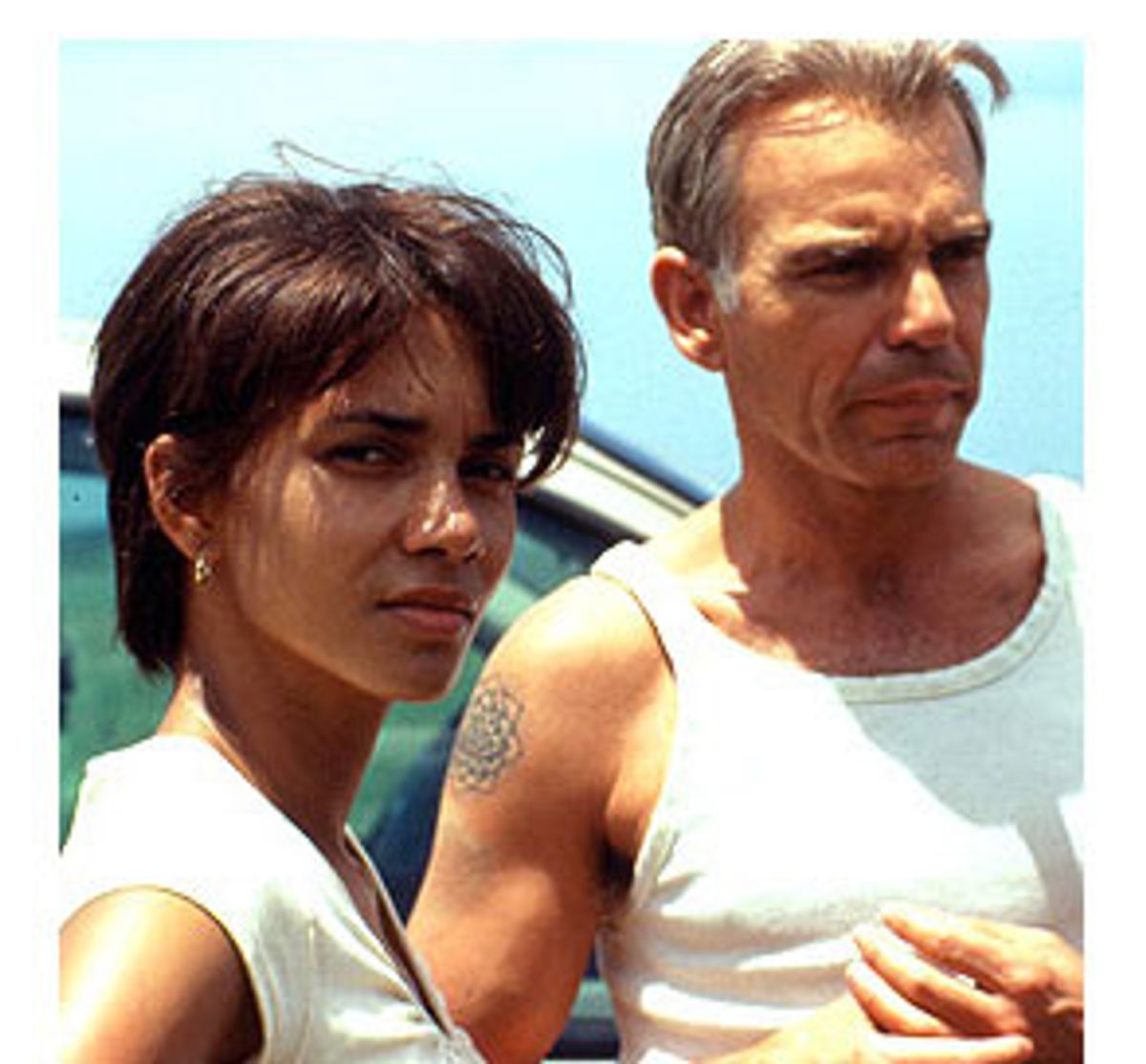

After a number of tragic events -- they pile up in this movie like corn husks at harvest time -- Hank meets a young African-American woman, Leticia (Halle Berry). Their pasts are uneasily but resolutely intertwined. They begin a secret romance that is, at first, little more than a rough mating ritual born of helplessness, frustration and raw need. But it slowly evolves into something else, and that's when "Monster's Ball" starts to heat up.

Forster, who is Swiss-born, approaches the South like an earnest schoolboy who has scrutinized the most desolate photographs to come out of the region -- pictures by the likes of William Eggleston and Steve Schapiro, the latter of whom Forster even nods to in a brief shot of a man holding a sign that reads "It's got to be somebody's fault" -- but who has never actually been there. "Monster's Ball" was filmed in Louisiana, but it's still a movie made by a stranger. This South is very, very poor -- so poor that it can't even afford extras. (There are numerous restaurant and prison scenes in the picture that are severely underpopulated even for rural Georgia. Sure, the poor, undereducated South is a lonely place, but it's not that lonely.)

Forster fixates on empty, dusty roads and ramshackle houses with grimy interiors. It's not that those things don't exist in parts of the South (they absolutely do); it's simply that we're constantly aware of the way Forster is pressing them into service to make his points.

Even the movie's very fine actors seem hamstrung in the movie's first half. Ledger is little more than a sensitive caricature. You feel some sympathy for him, but there's a vacant wateriness to him, and you need more from him to get a sense of him as flesh and blood. (It doesn't help that we're supposed to sympathize with Sonny when he vomits during the convicted man's "last walk." The movie does make the point that robbing a man of the dignity of his last moments is a pretty grave offense, but it puts the explanation of it into Hank's mouth, where it's made to look like an unfeeling brutality directed toward his son.)

Boyle, uncharacteristically, acts all over the place, bumbling through thickets of clumsy, rude dialogue about his no-good dead wife and, of course, anyone whose skin happens to be darker than his own. Racism exists, and it's evil: The last thing you need to drive that lesson home is a cardboard spokesman like this. And Thornton, at first, plays an empty thundercloud, a man who's on the cusp of becoming his father, if only he cared enough about his life to become anything. You can argue that the movie needs him to be that way in order for his big transformation to occur. But what good is it if you need to introduce a character as a cartoon in order to show how he's ultimately transformed into a human being?

But if nothing else, "Monster's Ball" proves that Thornton and Berry are pros. Their characters warm to each other, and we warm to them: Their love scenes, fierce and fumbling at first, ease into a cautious but sweet rhythm that's entirely believable. (Earlier, Forster had made it a point to show us two separate scenes of Hank and Sonny each grunting perfunctorily over a blasé hooker. Both go to the same hooker, and both grunt with identical vacancy. Like father, like son. Get it?) In her earlier scenes, Berry seems to be working overtime to play someone's version of an impoverished black single mother in the South, carefully dropping the "g" from any word ending in "ing." But both her slow-burnin' fervor and her flintiness eventually carve their way to the surface -- her performance becomes something moving and utterly genuine.

And Thornton loosens up with her, as Hank slowly realizes that he is not, and doesn't have to be, his father. In fact, he becomes something wholly different with Leticia, to the point where you can't believe this new person was lurking anywhere, even deep inside, the one we saw earlier. The grudging humor and rough warmth that Thronton brings to his character are wonderful, but they'd be even better if we hadn't been set up for them in such a calculating way. Handled more delicately, "Monster's Ball" could have been a fine little movie about human beings' capacity for growth and change. As it is, it's less than half a fine movie. The great surprise is that its actors come through in the clutch.

Shares