"Orange County" is a feebly pleasant surprise: It's not as cheap, loud and sleazy as it might have been, but it's also too eagerly well-meaning and indistinct to really stick. It's a piece of mildly entertaining, inoffensive fluff that drifts aimlessly for 90 minutes before lodging in the cracks of that ever-growing category: unembarrassing but unmemorable little pictures that, had their directors and writers fought to take a few extra chances, might have been something close to wonderful.

Colin Hanks plays a suburban California surfer kid whose life is changed when he finds an ostensibly Salinger-esque novel half-buried in the sand. He falls in love with it, rereading it 52 times; its author, a fellow named Marcus Skinner, becomes his hero. Hanks decides he wants more than anything to get into Stanford University and become a writer himself.

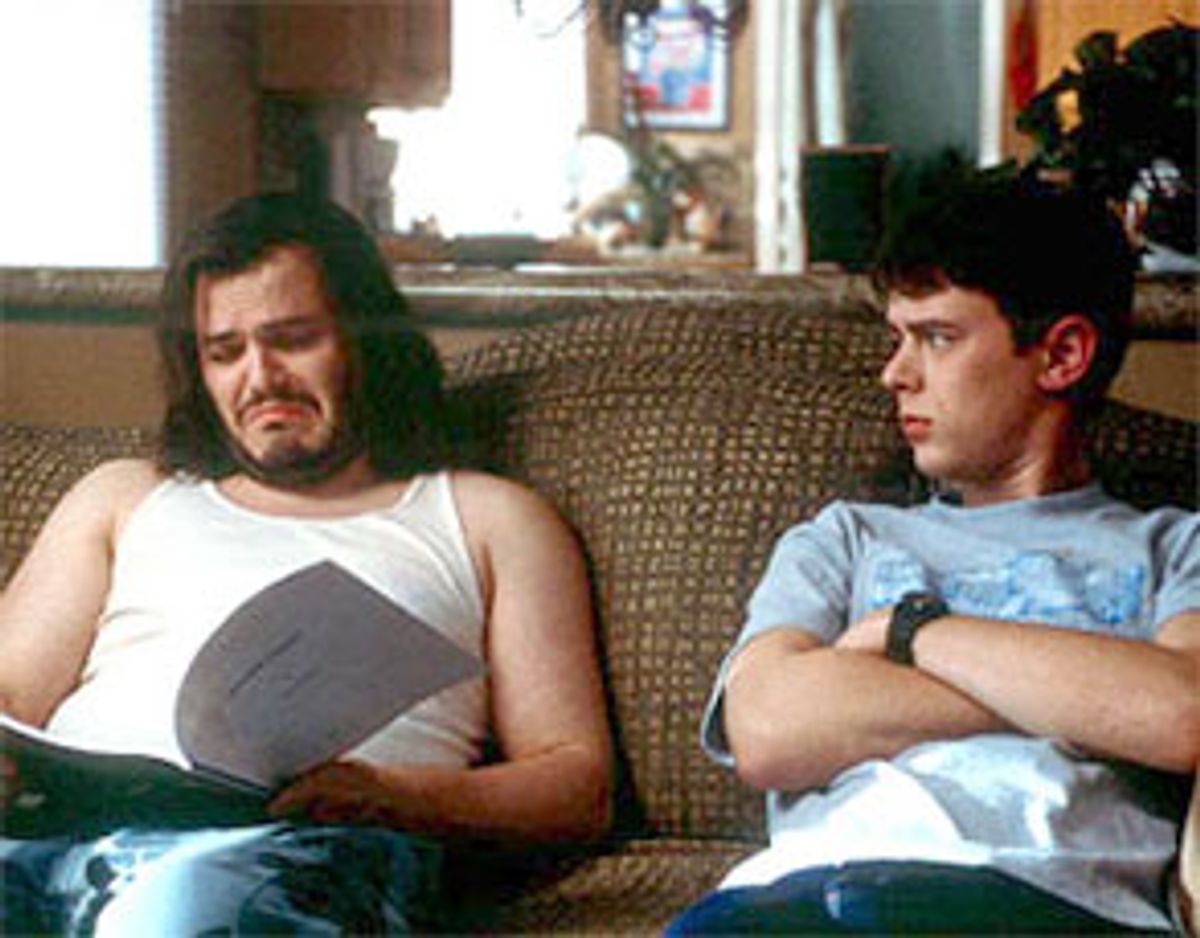

By cutting out surfing and dedicating himself to his schoolwork, he earns terrific grades. There's nothing standing between him and Stanford -- other than a careless guidance counselor with a split personality (Lily Tomlin), his essentially decent but unhappy wino mom (Catherine O'Hara), and his perpetual-parolee brother (Jack Black), who empties the families' over-the-counter analgesic bottles and refills them with super-duper painkillers and the like.

Needless to say, his application is rejected, and the rest of "Orange County" recounts his odyssey as he tries to break out of his bland-but-moneyed suburban existence and enter the glittering (as he sees it) world of academia. There's a gentle, sweet spirit at the heart of "Orange County" -- it's so sweet that you get the sense that the director, Jake Kasdan ("Zero Effect"), knew he had to rough it up, and he does so in the most obvious ways.

That's how we get Dana Ivey, as the dowager wife of a rich guy who just might be able to get poor Hanks into Stanford, accidentally raising a urine sample to her lips, thinking it's white wine. It's also how we get a shot of Black vomiting enthusiastically (he's perpetually recovering from his various recreational activities) onto the pages of a short story that Hanks has proudly shown him.

"Orange County" was written by Mike White (who also wrote and starred in last year's "Chuck & Buck"), and its tone is sometimes pleasingly off-center. When Hanks reveals to his rich, distracted dad (John Lithgow), who has long been divorced from Hanks' mom, that he wants to become a writer, his father snorts incredulously and says, "What do you want to become a writer for? You're not oppressed! You're not gay!"

The picture is set up so that Hanks is its most likable and most responsible character: You can't help rooting for things to go right for him, especially since those around him are doing their darnedest, inadvertently or otherwise, to muck up his plans.

But no one seems to have a clear idea of what overall shape or tone "Orange County" should take, least of all its director. The problem isn't that a teen comedy needs dumb puke, pee, fag and stoner jokes in order to sell. The genuinely terrific teen comedies of the past few years, "American Pie" chief among them, have included plenty of those jokes, but they've also raised the stakes for how those jokes should be handled and presented.

Context means a lot, and you get the sense that Kasdan understands at least that much: It's an unusual and affecting touch to show us Hanks reasoning with the family housekeeper in Spanish -- he's the only one in the household who speaks the language, or who even cares to communicate with her.

But the barf and urine jokes are simply dumb, and they don't blend into the movie in any organic way -- why do they have to be there? It's as if Kasdan had to work hard -- whether it was his own choice or a directive from the studio, we can't know -- to find places to wedge them in, no matter how awkward the fit.

Kasdan does draw out a loose, easygoing camaraderie among his actors. O'Hara has some marvelous deadpan moments, and Schuyler Fisk, as Hanks' girlfriend, Ashley, radiates youthful earnestness from within. (She also happens to be the daughter of Sissy Spacek; you'll recognize her translucent skin and elfin nose as DNA heirlooms.) Tomlin is terrific in her two small scenes, shifting between nose-crinkling ingratiation and ferociously sour wildcatting.

Black gets a reasonable number of laughs with his wild eyes and bird's nest hair alone, and he's the kind of actor who can turn a perpetual loser into a real character instead of a caricature. Hanks (son of Tom) has an honest, searchingly open face, and he knows how to use it. Or, rather, his great skill lies in what he doesn't do: He knows how to stand back and let the other characters' madness loop and ricochet around him. It's a stealthy way for a young actor to assert his presence, and it works here.

It would be easier to ignore the cracks and flaws of "Orange County" if it didn't wind itself up with a slurpy-smug "It's a Wonderful Life" ending that's completely out of tune with what comes before it. The movie forces us to believe that Hanks' character, in order to succeed at being a writer, has to make a choice between escaping from the familiar territory of home and embracing it wholly -- there's no in-between.

Anyone who's ever written a novel or short story, painted a picure or composed a piece of music probably knows that some of the greatest artistic conflicts and achievements arise from that great in-between. Apparently, that's too subtle a wave for "Orange County" to catch.

Shares