In Ali Smith’s new novel, “Hotel World,” a teenage chambermaid falls to her death down an elevator shaft hours before she was to have gone on a date to see Todd Solondz’s “Happiness.” For all the injustice of the character’s too-young death, you’re grateful for the mercy that she was at least spared sitting through the picture.

With “Storytelling,” Solondz’s 15 minutes would appear to be — finally, thankfully — up. “Storytelling” displays the same contempt for his characters that was the defining element of “Welcome to the Dollhouse” and “Happiness,” whatever cruelties and indignities the director can muster regarded with a stare of cold revulsion. But in “Storytelling” that attitude is so clearly Solondz’s shtick that getting offended by it would simply be rising to the predictable bait.

More than any other filmmaker, Solondz represents the worst trend of American indie filmmaking over the last 10 years: the movie as freak show. He belongs to a class of directors that includes Neil LaBute and Larry Clark, and documentarians like Errol Morris, Chris Smith (the director of “American Movie”) and Michael Moore, who can never resist getting laughs at the expense of those blue-collar people he’s supposed to be so concerned about. The common sensibility of these filmmakers is that they invite the audience to share their feelings of superiority to the people they put on screen. And too often, the largely white, urban, liberal, educated audience these filmmakers attract have been happy to join in, looking down their collective noses at the hicks and rubes and bourgeoisie trapped on the screen like specimens under glass. This kind of filmmaking is worlds away from the genuine fascination with the bizarre and grotesque shown by David Lynch, or even the delight and love that John Waters (a camp humanist) showers on his outrageous characters.

When directors and screenwriters and novelists talk about the pleasure they take in trying to figure out the behavior of their characters, they’re saying that those figures have a life of their own, a way of speaking and behaving and acting that they are discovering more than dictating. That’s part of the frustration and joy of creating memorable, three-dimensional characters.

When filmmakers go the other route of displaying superiority to their characters — and inviting audiences to join in that superiority — they’ve taken the easiest, cheapest way out. Todd Solondz asks nothing more challenging of his audiences than to feel confirmed, justified and finally superior in their prejudices. See, his movies say, the suburbs really are garish pockets of hell; foreigners really do stink (the subject of a memorable aside from “Happiness”); people really will always give in to their own worst impulses; and only all you enlightened, wonderful people out there in the dark laughing at them with me are smart enough to know.

Judging by “Storytelling,” the attacks on Solondz for engendering that kind of reaction are starting to wear on him. On the surface, “Storytelling” appears to be an act of self-criticism, the director wondering if his approach is feeding into something ugly in the audience. But this mea culpa is actually a j’accuse. It’s not Solondz, “Storytelling” says, who’s culpable for the derisive laughter directed at his characters, it’s us.

“Storytelling,” ostensibly an examination of how art is misinterpreted, is divided into two parts, “Fiction” and “Nonfiction.” The first story (whose plot I’m going to relate in full; so stop reading here if you don’t want to find out what happens) opens with Vi (the gifted Selma Blair), a college student having bad sex with her cerebral-palsy-stricken boyfriend Marcus (Leo Fitzpatrick, who was in “Kids”). As soon as they’re done, Marcus wants to read Vi his new short story. Cut to Marcus and Vi in their writing class, where Marcus is reading the story. Afterward, the teacher Mr. Scott (Robert Wisdom), a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, encourages the class to eviscerate it, humiliating Marcus. Shortly after, Marcus and Vi break up and Vi happens upon Scott in a bar and goes home with him. There the two have anal sex while Scott makes Vi say, “Fuck me hard, nigger.” (The scene is presented to us with a red triangle over the pair, Solondz’s preemptive strike against what the MPAA ratings board would surely have required cut. It’s a distracting, showy device — and it works. It’s a terse comment on how the ratings board treats adult moviegoers as infants whose must be kept from seeing what they deem inappropriate. The European version of the film required no such visual blocking.) Writing about the encounter for class, Vi turns it into a rape, earning praise from Scott for producing her strongest work yet, but having the class turn on her, telling her she’s merely using the words and situations for sensationalism.

There are plenty of satirical possibilities in that scenario: the cutthroat nature of student artists who are in starry-eyed thrall to their instructors. And of course the way racial fears and prejudices and taboos feed our sexual fantasies. Terry Southern might have turned it into explosive, corrosive comedy. Solondz’s treatment is gratingly literal and flat and obvious. Those disgusted writing students are the director’s stand-ins for the critics and moviegoers who’ve argued that the subjects of Solondz’s movies (child rape, obscene phone calls, kidnapping, murder) and his visuals (the cum shots of “Happiness”) are simply shock tactics, and that there’s no need to dwell on such unpleasant things. The students are presented as blinkered, sheltered, unable to face reality. And the audience members, those of us hip enough to get it, are invited to laugh at their naiveté (and also to feel superior to Vi, who has minimized her culpability by turning her encounter with Scott into a rape).

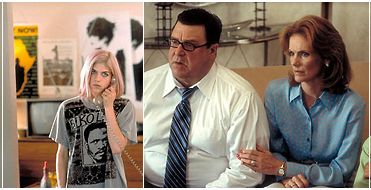

Then the movie turns to “Nonfiction,” where we meet the real red herring of the film, would-be documentary filmmaker Toby Oxman (Paul Giamatti). Toby is a nonachieving nerd, still floundering in his 30s, calling up a girl from his high-school class in a pathetic attempt for a date. He comes up with the idea of making a film about a real high-school student and chooses Scooby Livingston (Mark Webber), a stoner from a prosperous upper-middle-class New Jersey family who’s headed for early burnout. Asked what he’d like to do when he grows up, Scooby spins fantasies of becoming Conan O’Brien’s sidekick. Toby films Scooby and his family, ignoring the criticisms of his editor (Franka Potente, who seems like the only real person in the movie) that he’s playing them for cheap laughs. And that judgment is confirmed when Scooby sneaks into a New York screening of Toby’s film and hears the hip, invited audience roaring with laughter at him and his family.

Even more explicitly about how an artist feeds into the reaction of his work, “Nonfiction” offers a seemingly clear stand-in for Solondz in Toby Oxman. And the presence of Mike Schank — the damaged scratch-ticket devotee in “American Movie” who appears in a bit part here — would seem to be further evidence of Solondz’s critique of how filmmakers use real people as fodder. (Oxman even calls his film “American Scooby.”) In an interview in last Sunday’s New York Times, Solondz admits to being “unsettled” by “American Movie.” “People were laughing, uproariously,” he says, “and you have to question what that laughter is about.” He goes on: “Obviously the laughter that is most valuable is the laughter of recognition.”

But where is the laughter of recognition in Solondz’s movies? It’s certainly not in the scene in “Welcome to the Dollhouse” where we are invited to laugh at the hysteria and gaucherie of a woman whose little girl has been kidnapped. And it’s certainly nowhere to be found in “Storytelling.” (The audience I saw it with laughed loudly when Mike Schank appeared — as if to say, “Can you believe this guy is working?”) It’s not Toby Oxman, who presents Scooby and his family (headed by John Goodman and Julie Hagerty) as screaming, kitsch-ridden grotesques. (The caricatures of this family, particularly the obnoxious, spoiled little prince of a son played by Jonathan Osser, are anti-Semitic caricatures of Jews as brash, vulgar loudmouths.) And it’s not Vi who depicts her handicapped boyfriend as self-pitying and needy, or her writing teacher as Mandingo by way of the Iowa Writers Program.

“Storytelling” doesn’t represent any advance in sensibility for Todd Solondz. He’s still working in the cinema of hurt feelings, getting his revenge on the people who tormented him in school, the family that didn’t understand him, the Jersey suburbs that oppressed him with their stultifying sameness and falsely cheery veneer. (And given the fact that Solondz’s cinematic acts of revenge have won him all sorts of acclaim, you’d think he might be grateful to those people — and to Jersey — for advancing his career.) But “Storytelling” is a considerable leap forward in terms of sheer duplicitous craftiness. To the list of people who have mocked or misunderstood him, Solondz now adds critics and hipster moviegoers who, he contends, are guilty of seeing contempt in the people he claims to have depicted nonjudgmentally. Forget the college writing student mining her life for material, or the documentary filmmaker using his subjects; the real stand-in for Solondz in “Storytelling” is Scooby’s horrid, spoiled little brother Mikey, who hypnotizes his father in order to get his way. Is there any other explanation for why sensible adults would reward Solondz’s childish, self-centered whining with praise?