You can feel desperation buzzing around Danny DeVito's "Death to Smoochy" like flies around a corpse, and there are few things less funny than desperate comedy. It's as if DeVito set out to make a cult hit, a movie teeming with inspired weirdness that the squares out there in the audience just couldn't be expected to get.

But cult status is a patina that has to be earned over time (albeit, sometimes a very short time) -- it's not something you can use as a marketing tool before the fact. That wouldn't work even if you'd made a movie in which every joke comes in on the right beat, and DeVito hasn't. Most of the gags come with long, elasticky spaces before and after, as if DeVito thought we might need the extra time to let the jokes sink in, and those spaces sap our responses like black holes.

"Death to Smoochy" dangles precariously from two slender twin threads, a rambling, pointless plot (the script is by Adam Resnick) and Robin Williams' freewheeling noodling, and neither is enough to hold it up. DeVito starts by creating a funhouse mirror version of our own universe, in which everything is either completely reversed or at least just a bit off. That approach worked wonderfully in his 1996 adaptation of the Roald Dahl book "Matilda," which balanced noisy fun (including lots of deliciously mean-spirited Dahl-inspired jokes, which DeVito knew just how to pull off) with tenderness and restraint.

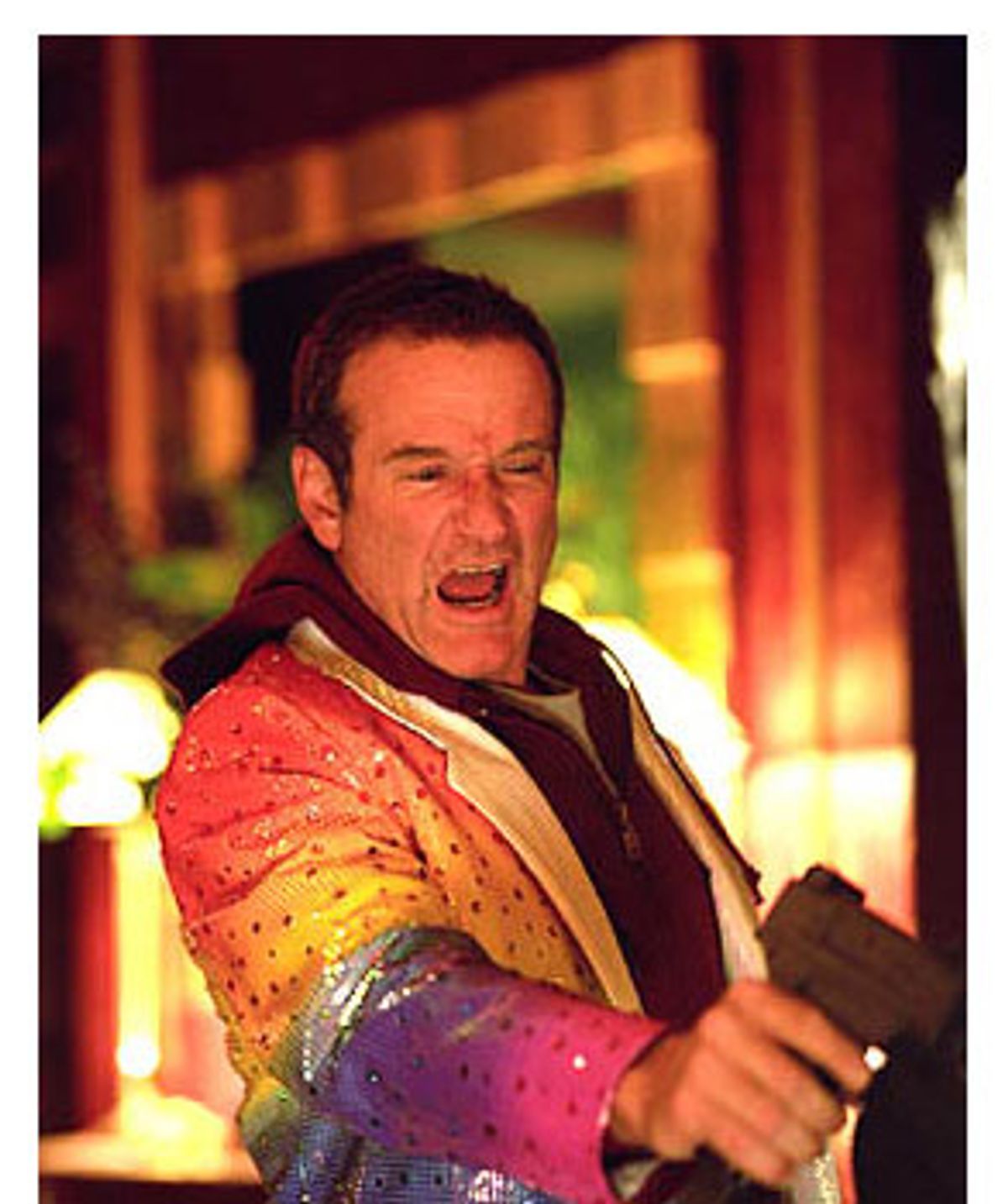

But "Death to Smoochy" is all noise with very little fun, and almost no restraint. It all kicks off when beloved kids' TV celebrity Rainbow Randolph (Robin Williams) is dismissed from his show in shame after a payola scandal. (The set of his program features a chorus of dancing dwarves who skip along on round steps in the shape of gold coins, each decorated with a giant dollar sign -- just in case we don't get how outrageously over-the-top Randolph's corruption is.) In a panic, network execs Catherine Keener and Jon Stewart (both of whom have virtually nothing to do here; they're just wooden pegs to anchor the movie's flimsier subplots) scramble to find a replacement. They come up with a mild-mannered, green-tea-drinking singer-guitarist named Sheldon Mopes (Edward Norton, understated but unfunny), who, when dressed in his purple, furry rhino costume, becomes the beloved Smoochy.

Smoochy's show is an instant success, but before long there are plenty of people who want to take him down. In the world of "Death to Smoochy," charities are run by thugs (Harvey Fierstein, with cartoon menace in his gravelly voice, heads one called Parade of Hope), and the friendly, boisterous redheaded owner of an Irish bar (Pam Ferris) is really a mob boss whose burly sons keep people in line by messing them up. Everyone wants a piece of Smoochy, especially Rainbow Randolph who, after his disgrace, becomes a deranged homeless type who sets out to ruin Smoochy's career (he starts by putting penis-shaped cookies into Smoochy's magic sack).

Williams cuts up with abandon, and some of his ad-libbed non sequiturs are as brilliant as you'd expect. ("Welcome to Fatty Arbuckle-land!" he snorts maniacally as he prepares those penis cookies on a giant outdoor grill.) But even he becomes wearying, and too early on. Almost all sentient beings who had to suffer through "Patch Adams" agree that Williams is at his best when he's not tied to a dorky script. But he still needs some sort of strong, flexible framework for his madness (as in, say, "The Fisher King"). When Williams tries to shiver the timbers of "Death to Smoochy," the whole thing practically falls down around his ears.

There's lots of manufactured outlandishness in "Death to Smoochy," including an ice-show extravaganza finale complete with a uni-horned opera singer. And yet the movie is simply no fun. As a satire of hype and consumer culture, it fails in the worst way. When Norton complains about the sugary kids' snacks he's supposed to hawk on his show -- he prefers to advocate healthful treats, like soy cookies sweetened with fruit juice -- Keener explodes at him: "This is not a sprout farm! You're here to sell sugar and plastic!" Her lines whiz past us and land with a thud somewhere out in the lobby. All that remains after the movie is over is a crummy pile of those lines, and the bitter knowledge that somewhere in the vast money-go-round of the entertainment business, we paid for them.

Shares