When you see "The Piano Teacher" in a movie theater you get a chance to go back in time, back to the days when French movies were titillating, provocative and kind of smart -- when foreign cinema was a raincoat affair. I felt a little dirty after watching it, but I kind of liked that feeling, too. "The Piano Teacher" is now offering that feeling only to New York moviegoers, although viewers in at least a few other cities should get their chance soon.

Professor Erika Kohut (Isabelle Huppert) gives piano lessons at a Vienna conservatory (yes, the movie takes place in Austria, and director Michael Haneke is German-born, but its focus on sex and intellectual rigor is French all the way). She's a harsh teacher who looks blankly out the window while her students play, then belittles them for missed notes, or tells them they'll never be good enough.

It's a pretty drab existence for Professor Kohut, made worse by the fact that she's seemingly sacrificed everything else for her art. Haneke, adapting a novel by Austrian writer Elfriede Jelinek, puts her in a shabby apartment with her ridiculously domineering mother (Annie Girardot). They fight nonstop. Her mother treats her like an untrustworthy teenager even though she's coming up soft on 40. And weirdly -- or not, since I don't pretend to be European in my outlook -- at the end of the night the two of them climb into the same bed.

We soon find that Professor Kohut is, well, a big old pervert. One day after a lesson she visits a sex shop. There we find out that she's the kind of person who gets off on the smell of the video booths as much as the pornography. And she's into voyeurism, too. Heavily. She hides all this from her mother, of course, but we still have some sense that she wants to get caught -- that she wants others to know how debauched she is.

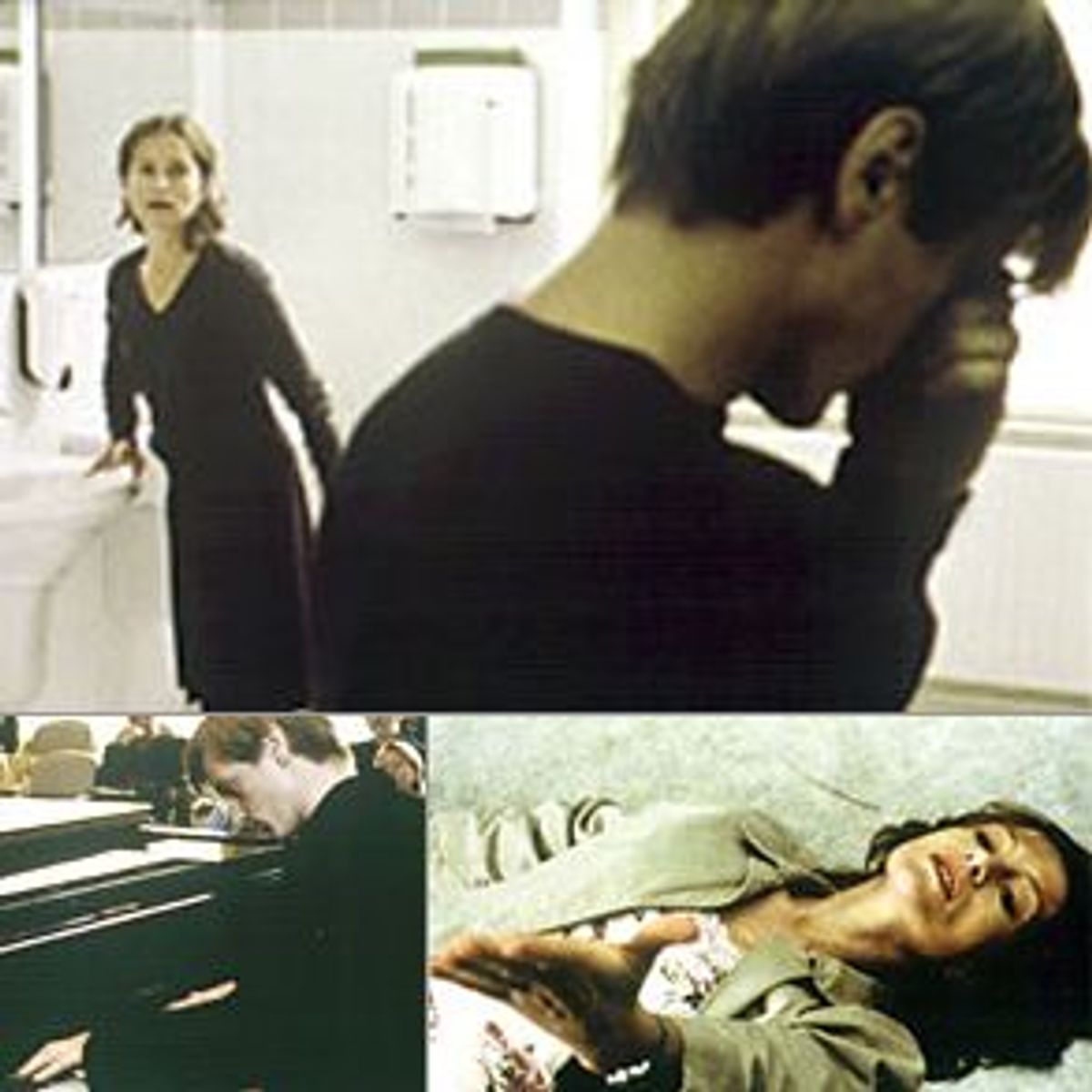

We get a chance to find out for ourselves when Kohut ends up with a studly and much younger student (the grinning, saucy Benoît Magimel). In one of the weirdest, most uncomfortable sex scenes ever, he makes a move on her in a bathroom at the conservatory. She's into it, and takes control immediately. Yet every time he advances she backs off. She wants to get him off. He leans in for a kiss. She says she'll tell him what he can do to her later.

And that's where everything disintegrates. When she gets into the details of how she wants to be dominated -- almost abused -- the movie turns into a power struggle that gets more sordid with every scene. I'll leave the details to the film; nearly all of them are verbal rather than physical. Let's just say that with her dominance subverted, Kohut becomes more and more desperate, and every time she gets more desperate she makes a slip that drags her down even further. By the end she's a melted pool of neurosis.

As with any truly interesting work of art, there are a million ways to read "The Piano Teacher." Hardcore old-wave feminists (if there are any left) will probably hate this film: It's almost like librarian porn, where the smart, reserved woman turns out to be a wild sex beast. And at the end of the day, she really just wants to be tied up and humiliated.

For fans of formal cinema, Huppert's performance is pretty much unbelievable. (She won best actress at Cannes last year; co-star Magimel won best actor and the film took the grand prize.) Haneke just levels the camera on her face and lets us stare at her for what seems like forever. Huppert is so good that we can read everything she's thinking, even watch her change her mind, without seeing her move a muscle. She's playing the kind of character that seems overwritten to the point of silliness, yet we never doubt her for a second.

But I was interested in another way, because this is a smart movie that knows its classical music, knows its Freud and knows its Sade. It's the only movie I've seen that quotes German theorist Theodor Adorno -- and it quotes him on the composer Robert Schumann. I have no idea if I'm right, but the way I see it, "The Piano Teacher" is primarily a movie about the moment before madness.

Kohut even tells her would-be lover about this moment, and as the film goes on we wonder if she's trying to engineer her life so that she can experience whatever lies just this side of insanity. Perhaps Kohut thinks she can attain it, or at least try it on for a while. Haneke's movie captures, brilliantly, what happens when she can't.

Shares