Here's the main thing about "The Fast Runner," a strange and memorable movie that comes to us from the Canadian Arctic and is the first feature ever made in Inuktitut, language of the Inuit people: light. I mean, this is one bright movie, all dazzling expanses of ice and snow and sea and sky; the ghostly interiors of igloos by daylight and by firelight. You could read a book by it. It's a difficult film to follow and at 172 minutes is maybe a half-hour too long. But simply as a sensory experience "The Fast Runner" (which opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles) is amazing; I can see why some of my critical colleagues have gone gaga for it. In some of its early scenes, those enormous vistas of brilliant white seem to fill up your ears, your nostrils and the inside of your head. It's like swimming in illuminated milk.

Furthermore, it eventually delivers a compelling human story that's both mythic and realistic; it might not be a stretch to call this an Inuit version of "The Iliad." If you have the patience for this kind of thing -- and I respect the fact that not everybody does -- then don't miss it. But for God's sake catch this one in the theater and not on home video (unless you have one of those TVs that cost as much as your car). Director Zacharias Kunuk, an Inuit himself, shot the movie in widescreen digital video, and that shimmering, hard-edged medium may never have been put to better use. Seeing it on a small screen would be deeply beside the point, like looking at "Guernica" in an art-history textbook.

Whatever combination of talent, happy accident and hard work was involved, "The Fast Runner" is, for all its flaws, an enthralling discovery. It results in large part from a concerted effort by the Inuit to preserve their culture and heritage in a modern context, and anybody who believes such projects are doomed to p.c. irrelevance will be confounded by this daring and original film. Screenwriter Paul Apak Angilirq (who died in 1998, while the film was still in production) tells a story drawn from indigenous legend without the slightest hint of sentimentality or New Age mysticism. Its cinematography (by Norman Cohn, an American who has lived in the Inuit province of Nunavut since 1985) is contemporary and thrilling, its acting (mostly by nonprofessionals) is assured and relaxed and its setting is both utterly alien and entirely familiar.

Figuring out what's going on in "The Fast Runner," which is set in a small Inuit community somewhere in the premodern past, can be a bit of a challenge. Besides, you may be too busy marveling at the details of daily life that Kunuk captures so sharply -- women sitting around scraping fat and gristle from caribou hides, men constructing a special ritual igloo -- to remember that this is a drama and not some PBS documentary. (As a montage of outtakes and behind-the-scenes footage accompanying the closing credits makes clear, the actors and crew are in fact 21st century people who wear designer clothing and listen to Walkmans.)

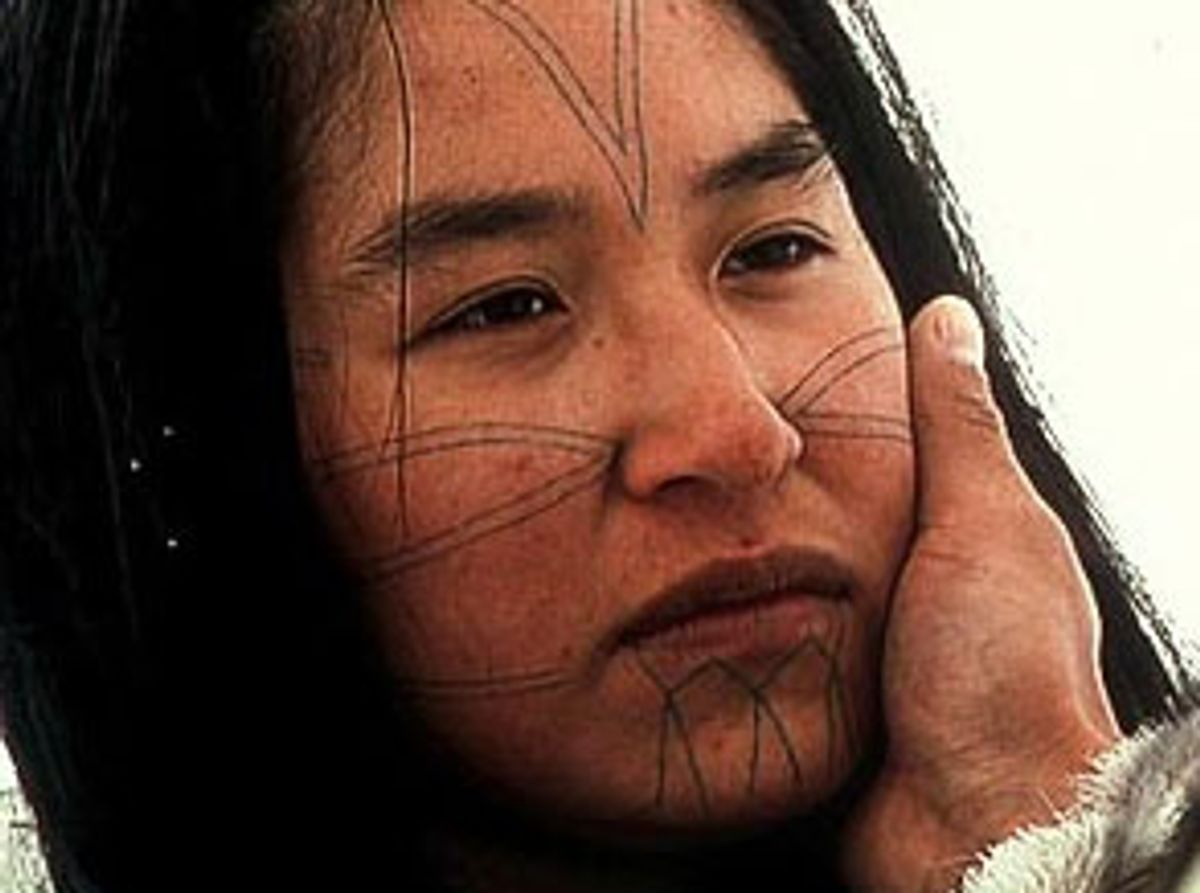

On one level, "The Fast Runner" purports to be a tale of magic. An evil shaman has divided the community into two warring clans, and some years later the grown-up sons of the two families, infants when the spell was cast, must face off in an inevitable confrontation over a woman they both want. Atanarjuat (Natar Ungalaaq), a handsome, playful young man noted for his fleetness of foot, miraculously escapes from Oki (Peter-Henry Arnatsiaq), the rival who's trying to murder him, and becomes the redeemer of his people. But Kunuk tells his story primarily through his realistic characters and often-astonishing imagery, not through mystical rhetoric. Amid all that bright white space, we see Atanarjuat's feet flying through the snow, the village's exhausted sled dogs after a day of hunting (if you're ever in doubt about who's evil and who's good, the treatment of the dogs is a surefire sign) or the women -- working as hard as the dogs -- who, as we learn, are naked under their elaborate caribou parkas.

"The Fast Runner" is ethnography from the inside out; it explodes the mingled awe and contempt with which the movies have generally viewed indigenous people and gives us recognizably flawed human beings. For its makers, the film is clearly a labor of love, and at least in this case love has meant avoiding easy falsehood or sentimentality. The film never flinches in depicting the subordinate position of women or the griminess, cruelty and harshness that were part of traditional Inuit society.

Apak's characters are apparently taken from his conversations with Inuit elders who inherited fragments of the oral tradition, which ought to remind us that genuine myth is often far more realistic than the inflated archetypes marketed by Hollywood. The people in "The Fast Runner" are just as capable of duplicity, hypocrisy and sexual infidelity -- or of profound generosity, enduring love and vulgar humor -- as anybody you know. Atanarjuat and Oki may belong to the tradition of Hector and Agamemnon or the Hatfields and McCoys, but they're also just a couple of testosterone-pumped guys -- one of them easy and confident, the other jealous and petty -- who want the same girl and can't live peacefully in the same neighborhood. If they lived on your block, they might be racing rebuilt Chevys.

Kunuk also gets powerful, unforced performances from the rest of his cast. Sylvia Ivalu is especially good as Atuat, the woman both men want who becomes this story's Penelope when Atanarjuat, who escapes naked across the ice in the movie's most stunning sequence, is missing and presumed dead. Then there's the gamine Lucy Tulugarjuk as Puja, Oki's sister, a Helen of Troy type who seduces Atanarjuat, leading, as in any myth worth its salt, to no end of trouble.

If you stick with "The Fast Runner" for, well, frankly, a pretty long time, the confusing events of its early scenes are more or less explained and the shaman's generation-old curse is properly dealt with. But what sticks with you is the daring and originality of Kunuk's compositions, the film's combination of the strange and the familiar, the mythic and the everyday. Its people, so ordinary and so exceptional, against that endless field of Arctic light.

Shares